Agile was created by some official organization, right? Wrong. It was invented by a group of software developers who got together on February 11, 2001, at the Snowbird Ski Resort in the Wasatch mountains of Utah to talk about ways to make software better and improve the relationship between developers and clients.

It’s been 16 years since Agile’s creation, and by all accounts it does seem to have worked better than waterfall methodologies. But it is not a perfect solution. The Chaos Report shows that up to 23 percent of projects using Agile methodologies still fail.

If we look at Agile as a movement, then as with any other movement, we should ask: can we do better? Specifically, can we use the Code Review to improve Agile? And can we get the Scrum Master to do it?

The First Crack Appears In Agile: The Non-Technical Scrum Master

Agile has many descriptions, depending on particular perspectives, but fundamentally Agile is quite simple. The description of that original meeting where Agile was created tells us it’s just a way to implement lightweight development processes to make software better.

We can boil Agile down into four basic principles: trust, collaboration, improvement, and accuracy.

The biggest framework for implementing Agile has been the transition of teams into using the Scrum Methodology, which was meant (in part) to help us achieve the four goals stated.

When I started my career I always had a hard time because it felt like no matter what project I joined there were always far more problems than seemed normal. The deliveries were late, bugs were rife and the code was always badly maintained. When I heard about Agile I thought to myself: this sounds like just what I need to learn about. So I spoke to my partner, allocated the money from our savings (£1000) and booked myself into a one-week intensive course in London to learn to become a Scrum Master.

I turned up on the first day; the course was a packed training room of some 20 people. The first task of the day was to go around the table and introduce ourselves. To my surprise I was one of only a few developers in the entire room. The large majority of people in there were from a non-technical background. This really surprised me because I knew the history of Agile, I knew about that meeting in the ski lodge and I knew there really should be more software developers in that room.

I recently did a quick audit on LinkedIn. For the search I did in London, of people with the current role of Scrum Master, only three of the 10 people I looked at have a software development background.

It would seem from my own anecdotal story and a perusal of LinkedIn that Agile is being dominated in a large part by people who aren’t software developers, and that poses a potential problem.

The Most Important Part Of Scrum

If you read the Scrum Guide, one of the responsibilities it states for the Scrum Master is: “Helping the Development Team to create high-value products.”

What exactly does it mean to create a high-value product? I think most of us would agree (in principle at least) that value exists on both the exterior of the product and the interior. That there is no point in shipping software which works but whose code is a mess. We know that organisations pay us a lot of money to write this software, and it is our responsibility as software professionals to do the job properly.

Even though we seem to know the importance of code quality collectively, very rarely do we manage to consistently ship high quality software on our projects. In fact, one study performed by Cast Software suggests that there is over $1,000,000 of technical debt, or problems with the code quality, in the average code base. Why is this?

In my experience the main reason is that teams are haphazardly assembled—often with people who have never worked together before—in an unorganised manner and are just expected to get on with it and deliver. At the start of the project they talk about all the right things—TDD, code quality and refactoring—but as the project progresses and as the demands pile up, slowly but surely little cracks start to appear. Functions go un-refactored. Tests become weaker; architectures begin to fragment.

As a software team we can throw all the Agile principles we like at it, but in the end technical debt will always bring a project to its knees. It is impossible to keep overlaying bad code over bad code and papering over the cracks. At some point we fail.

Be under no illusion, the biggest threat we face to our projects is technical debt. And if shipping a high value product is the most important part of Scrum, and Scrum is the dominant methodology, we arrive at a clear conclusion: we have to control technical debt if we want to be Agile.

The first step to control technical debt is to identify it. And we have been given the most powerful of processes to identify this technical debt. It's called a code review!

The Purpose Of A Code Review

The easiest way to ensure high quality is to stop the production of bad quality. By inspecting every change to a code base we can apply a standardised set of principles which will help us to improve quality. But what are the high level objectives for this quality, and why is reviewing code so important?

There are three main reasons we should review code:

1) Protect the employer / client from bad code

Like any product, software code needs some level of inspection during and after its creation so that any drops in quality can be identified as soon as possible. Some of the potential problems we might identify are:

- Missing unit tests

- Poor architecture

- Bad dependency management

- Coupling problems

2) Improving the skills of the contributors (knowledge sharing)

A code review forces discussion. Discussion can often lead to debate, and a certain amount of debate about code can be a really helpful tool to increase overall knowledge and understanding.

3) Refining the architecture and software model

If every developer is allowed to implement their own architecture, you can easily end up with lots of optimised but fragmented ideas in the code base. Over time this becomes unmaintainable. It's better to have guidance and direction on project architecture. The code review provides a mechanism to slowly bring everyone's separate interpretation of how the software should be built into a single defined vision.

The Technical Leader (Who Reads Code)

So far we have established that there are strong pointers towards Agile being (at least in part) concerned with code quality. And that code quality needs to be addressed pragmatically with a code review.

There is this idea in the software community that software teams are egalitarian.

That all the developers have an equal right to commit code to a code base and to make decisions on how the code should be conceived of and structured. It’s odd, because in almost every other profession where teams are used this notion doesn’t exist. Architects have senior partners, builders have foremen, and in sports you have a captain or a coach.

Why would software be any different? It shouldn’t be; a software team should have a competent technical leader. This leader should actually spend a portion of his or her time reading all of the code that gets committed.

The right way to implement a code review is to actually structure your teams so that this leader has commit rights that are higher than those of the other developers. They make the final call on the code being integrated.

At least one person on the team needs to take responsibility for the quality of the code. The point is that this person has an important job to do by reading code and it is their responsibility to ensure the code is of a high standard.

Ensuring things are done properly in any field requires that you make someone accountable. Accountability is usually given to a leader. This leader is given higher status, but at the same time they take on more risk because they take ultimate responsibility.

From a software perspective a technical leader has many responsibilities; they should understand the core interfaces and the deep architectural issues, and they should be able to have vision on the direction the software design needs to take. They should be able to formalise designs that the developers come up with and make the entire code base consistent.

I have come across many architects, technical leads, and team managers, yet rarely do I come across people who just sit down and actually read code.

The Scrum Master (Who Reads Code)

The fact that the role of the Scrum Master is being done by non-technical staff leads us to a predicament. The current and dominant implementation of Agile does contain a mechanism for the provision of code quality.

However, the role that is most likely to take responsibility has come to be dominated by professionals whose background is not in software development. As such, there is an impediment to reading code for the majority of Scrum Masters.

What we really need to do is step back for a moment and consider if we could architect a better way of doing things. If we could upgrade Agile—if we could remake it—then how would we redefine the role of one of our key players?

I believe this key player would be responsible for monitoring the code. I believe what we need is not just a Scrum Master but a Technical Scrum Master. Not only will this new role help with the management of the team, but they will also be involved with the inspection of the code.

Migrating To Agile 2.0 Using Scrum

So Agile is dead. But what does that mean? I think it means the next evolution of Agile. We can call this Agile 2.0.

The move from Agile 1.0 to 2.0 is for me one that includes a heavy emphasis on inspection of code. Since we can’t do this in today’s setup of Agile using mainly Scrum because the key player is not a developer, how do we move on?

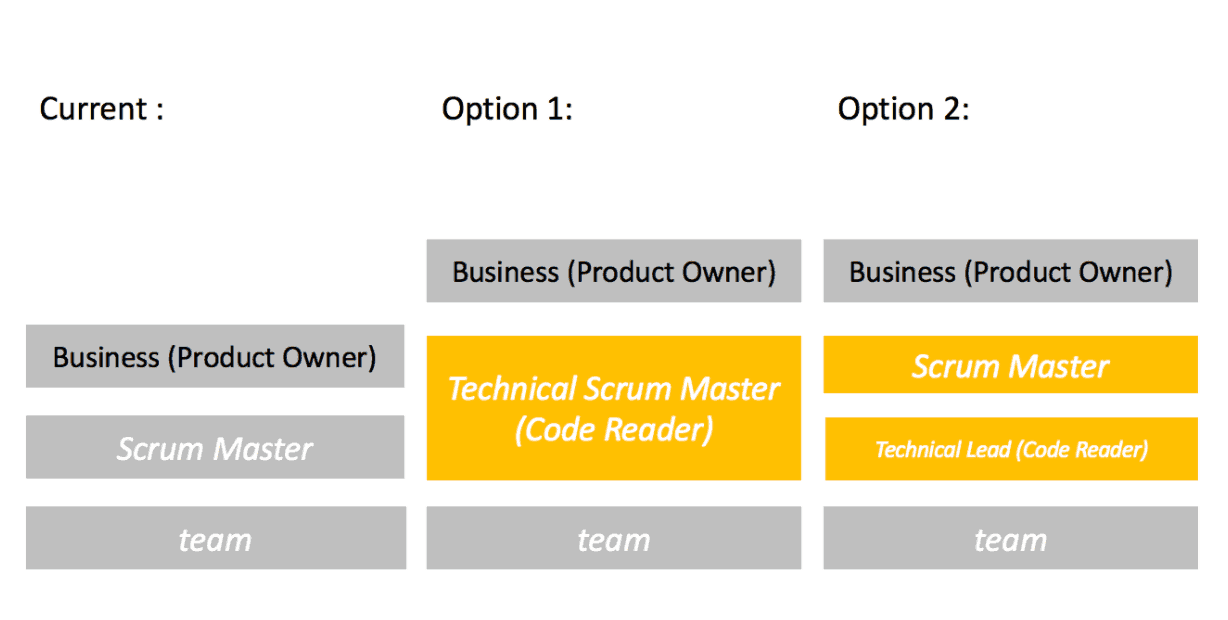

A Scrum Master who wants to improve Agile has two options:

Option 1: They Learn To Read Code

This might scare a lot of Scrum Masters from non-technical backgrounds. It can take years to learn a high proficiency of programming. But there are key things that can be picked up on relatively easily, such as missing automated tests, or bad dependency management.

It is possible that non-technical people could learn to recognise problems. For example, one trick I show people to check for missing unit tests in a feature branch is to comment out business logic and run tests.

Code coverage tools can sometimes be useful too. No one should be afraid of simply opening up and looking at code. Even non-technical people with a minimum amount of training would be able to spot really really bad code (for example, code with no tests).

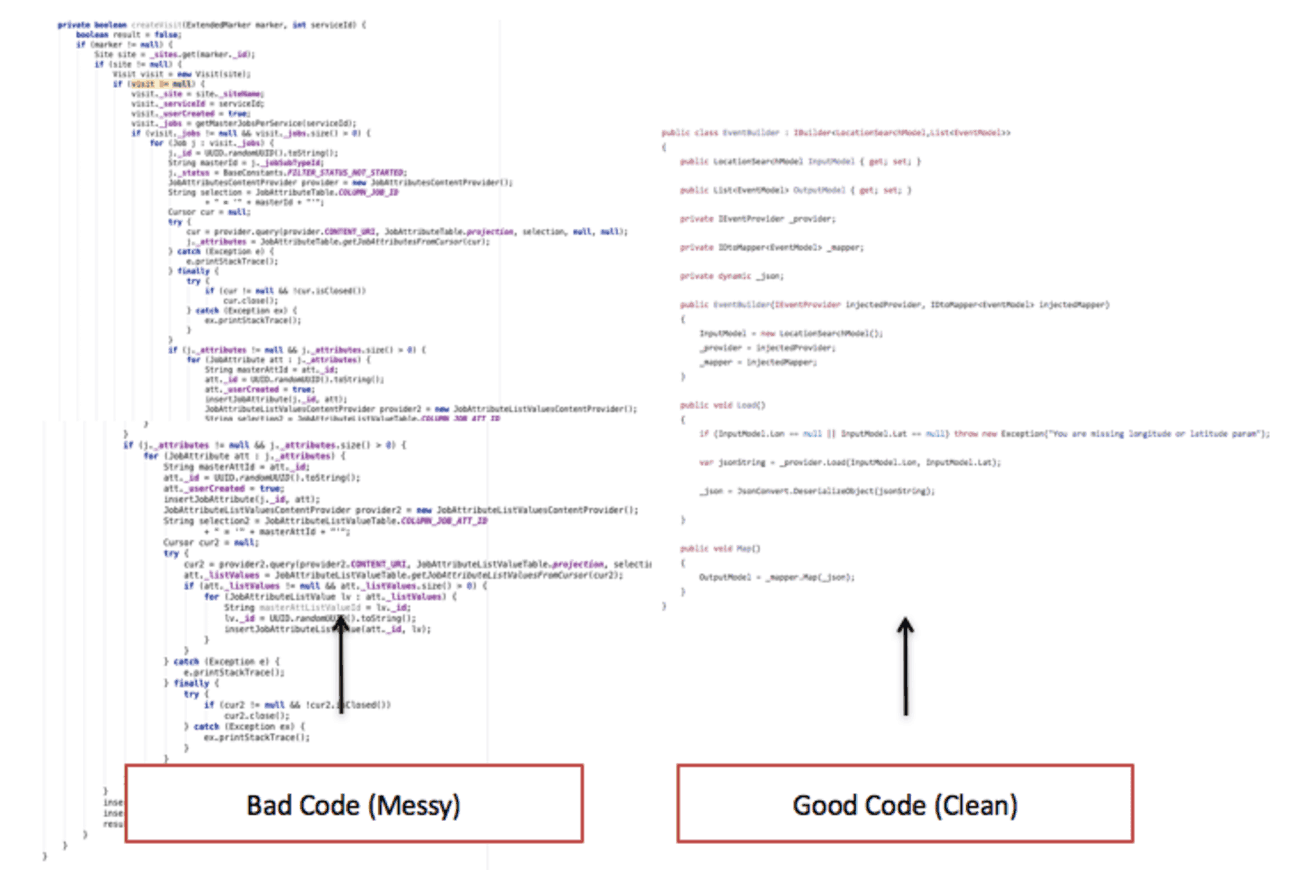

When I do presentations to non-technical business leaders about what good code looks like I usually show them this picture:

You can see just from the shape how the one on the left looks messy and the one on the right looks clean.

Option 2: They Work with a Nominated Code Reader on the Team

This is probably the most viable option for most current Scrum Masters and can be a great stepping stone. Since it is the Scrum Master’s responsibility to help the team create a better product, he or she should work with the team to nominate one developer who can read all of the code that is checked-in and make sure it is in line with the quality metrics that the team has set.

Pair Programming

In recent years pair programming has become more popular. Pair programming can be seen as a way to mitigate the need for a code review. However, it’s important to remember that even pairs may make the same mistakes or implement weak architectures, just as solo programmers do. There may also be a less experienced member within the pair.

The code review may be lighter when reviewing pair-written code (since pair-written code produces fewer problems), but should still be carried out because there needs to be a single point of control/responsibility.

Conclusion

Agile was invented as a way to use lightweight processes to help mend the divide between businesses and developers.

It started with noble goals and it seems from historical reference that the original intent was that developers would use Agile; it would be their tool. But somewhere along the way this idea seems to have been sidelined.

Non-developer staff started to train in the dominant implementation of Agile (Scrum), and have used it as a way to manage development teams.

But in the process, they left out a key requirement of implementing Agile: the inspection and improvement of the actual code that is running our software. Because of this, the average code base has a lot of technical debt.

Poor code quality costs businesses a lot of money and exposes them to risk. So we can suggest an improvement on Agile, which will re-establish the code review as a definitive part of its recommendation. It will upgrade Scrum so that the Scrum Master will begin to take responsibility for code by actually reading it.

In a transitionary period, current teams can nominate a code reader who will work with the Scrum Master. In the longer term, the Scrum Master can learn to read code themselves so that they can really start to help the team be Agile!