Practice, practice, practice

Like most programmers, I am passionate about software development; it’s natural for me to want to get better at it. So, often I look up how to do that online.

But it seemed that everywhere I looked, people were saying: “Practice, practice, practice.” I thought: “Ok, so what?” Then, I looked some more and stumbled on things like: “write more code!”, “Code Katas are the way!” or “a programmer should practice programming by programming.”

Ever asked somebody about career advice and all you got was “Follow your passion!” It felt the same to me.

“Practice is the key to success”

We’ve heard such trite expressions so many times.

Such kinds of advice lead us to exactly one place: nowhere land.

I don’t know about you, but when I’m going out on a trip, I don’t want to start the journey without knowing what direction to take.

Have you actually read before how developers should practice?

Have you actually read before how developers should practice?

In my quest for answers on how we developers can perform deliberate practice, I’ve had to read many books, watch many videos, and take copious notes from blogs.

Now, I want to save others the same frustration through which I went. I’ve gone through all these notes and books and compiled some of the best ideas into a list that hopefully you’ll love and apply to your work.

Below you’ll find a 7-step framework that we all can try. You’ll then be able to incorporate your own tactics in addition to those I suggest.

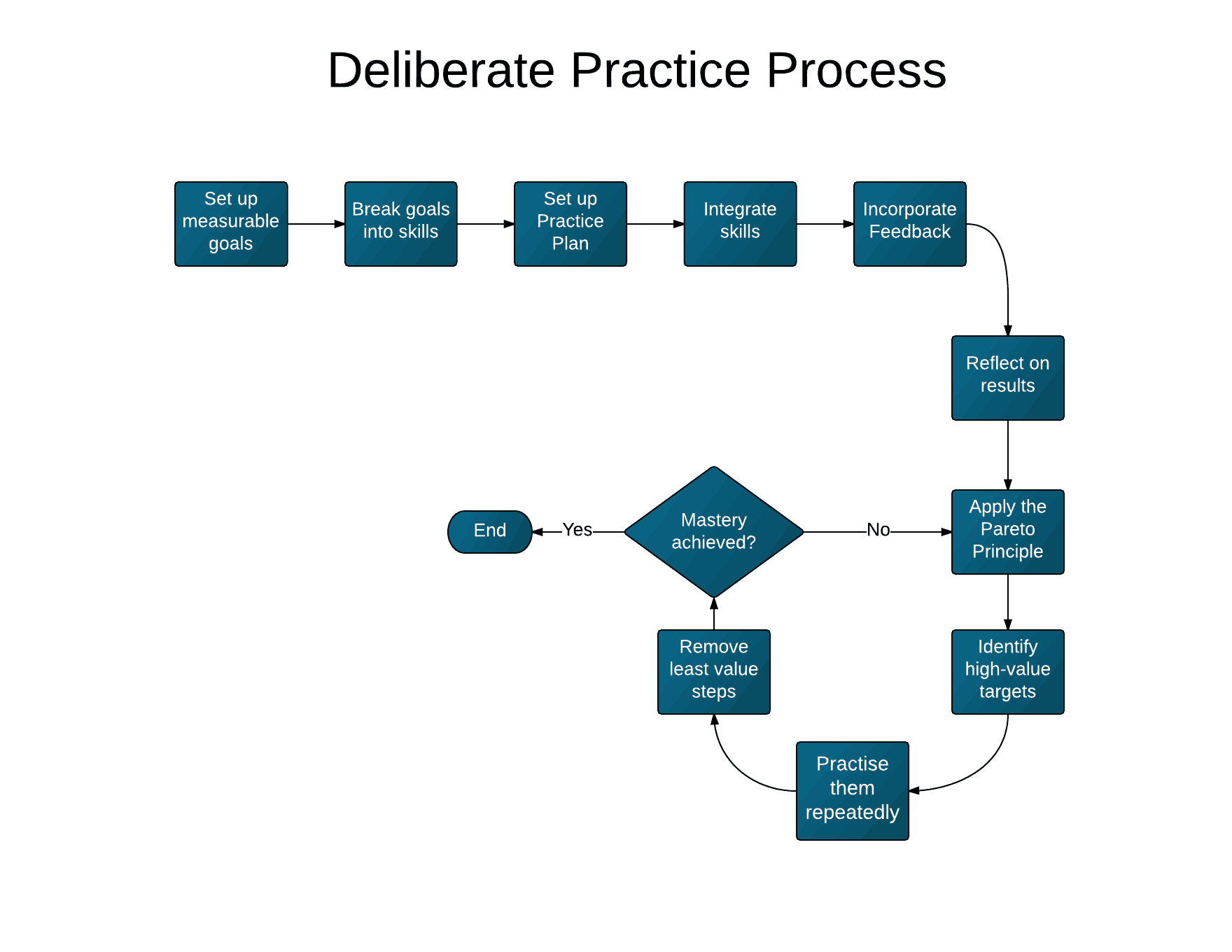

Here’s an outline of the framework:

- Set up your measurable goals: know where you’re going.

- Break the goals down into discrete skills.

- Set up your practice plan: the operating procedure for you and your peers.

- Integrate the skill: understanding others’ code.

- Incorporate feedback: staying on target.

- Reflect on your results: avoiding stagnation.

- Apply the law of the vital few: what’s your 80/20 like?

1. Set up your measurable goals

Never start an endeavor before having clear goals, especially on large scale projects.

Goals should be made clear in your head so that they help you avoid getting distracted by less important work along the way.

To then achieve it, you need to have a sense for what the destination will look like.

Example of a bad goal: Understand system X thoroughly by the end of the year.

A better goal could be: Understand the 3 most used features, A, B, and C of system X by the end of the coming fortnight.

Note a couple of things about this rephrased goal:

- Sub-goals are clearly defined: ‘thoroughly’ or ‘the 3 most important features’ are too vague unless these 3 are listed.

- They have a deadline that is not too distant. It should be a time frame that you can reasonably estimate.

Your next steps can include consulting the architecture diagrams, looking at the user interface or asking a colleague for a walkthrough of the application. The idea here is to get a high-level sense of what you can expect to do on the project.

When you have identified your high-level goals, make sure you understand how they all relate to each other. When goals follow each other, they will give you a sense of progress as you complete each one, and an overall direction on the project as well.

Tip: When you commit to goals, use the principle of consistency by making your colleagues aware of them, thereby making you more likely to keep up with them.

For a few other ideas on how to make this idea work for you, I invite you to read this article that’s based on the Influence book by one of my favorite authors, Robert Cialdini. It shows you how you can apply one of the most powerful psychological forces in your own life.

Remember the saying: You can't hit a target that you can't see. Therefore, make sure you know what you want to achieve beforehand.

For each goal, ask yourself these questions:

- Is your goal measurable? How will you know when you complete it?

- Does it have a definite deadline?

- Is it clear and focused?

- What high-level documentation can you use?

- Whose help will you need to achieve your learning and practice goals?

2. Break the goals down into discrete skills

After you have defined definite and measurable goals, you'll need to identify what skills you need to achieve them.

Small and well-defined skills are easier to achieve and give you the confidence you need to pursue your goals.

This is where you'll identify the libraries, frameworks, and even modules of the project itself.

For example: If you're using Maven, consult the pom files to see them. If you're using a major IDE, it should have a way to visualize it, e.g. here is an example of how to do it in IntelliJ.

Ask yourself:

- Which parts of the libraries/frameworks used should I learn right now?

- How are the libraries most frequently used on the project?

3. Set up your Practice Plan

Just like a well-managed software project is broken down into specific deliverables, so should your practice sessions.

Next you’ll write a document to comprehensively list all the skills, in what order you need them, and the expected time each will require to complete.

A side-effect of writing this document is that, just like writing the learning tests (see the next step), it is ready to be used by the new developers in your project without needing to repeat the whole process each time.

This will become the operating procedure to which your newcomers will refer and improve upon.

Kind of questions to ask yourself when writing the Practice Plan:

Have you listed all the skills you need?

- Are the skills small and achievable within the time estimates?

- Will the next person reading this document have everything he needs to get up and running as soon as possible?

4. Integrate the skill

Now, you’ll learn how to practice this skill in context. Practicing in context will allow you to make progress faster because you will be learning how to actually use the skill on the project and not just practice without any clear direction.

Don’t try to integrate code and learn it at the same time; that will be quite hard. Explore it first and then integrate it.

One approach that you can try is to write “learning tests.”

If there is a library with which you’ll need to be familiar, follow these suggestions to familiarise yourself with it in the context of your project (of course, you’ll still need to consult the reference for the library).

These steps are applicable to third party code as well as the project’s own modules:

- Look at some scenarios in which it’s being used in the project.

- Write some tests that use the library in such scenarios.

- Verify your understanding of the new concepts by making variations to the concept that will validate your knowledge.

- Then, and only then, you should integrate the code in new code that you write.

Incidentally, following these steps will force you to think of the long run. The next developer will be able to get started more easily on the project. Learning tests may even help you catch backward compatibility issues that can arise when you later migrate to newer library versions.

I first came across this “learning tests” gem in the fantastic book Clean Code by Robert Martin. In it, Martin explains:

“In learning tests we call the third-party API, as we expect to use it in our application. We’re essentially doing controlled experiments that check out understanding of that API. The tests focus on what we want out of the API”.

The salient point here is to understand that the more your practice resembles new code that you're going to write, the more effective your learning will be.

So, when integrating the skill, ask yourself:

- Do your practice sessions resemble the kind of work that is expected of you when you’re actually going to use it?

- Do you repeat the maneuvers at which you’re the weakest?

5. Incorporate feedback

5. Incorporate feedback

Feedback is the critical component to your practice sessions. You use it as a guide to help you know whether you’re on target or not.

You can receive feedback from several sources:

- People, e.g. your team mates/ mailing lists.

- Tests, e.g. via tests in your development environment, your continuous integration server, etc.

The feedback loop is the path between doing something and receiving the results. To accelerate your progress, it makes sense to strive to shorten the feedback loop.

This is why automated test practices like Test-Driven Development (TDD) are effective; you can get feedback quickly and easily, whether in your IDE or your reports from your continuous integration server.

Here are some other ways you can shorten the feedback loop:

- Configure your IDE to run tests on save/compile. InfiniTest is a plugin for both Intellij and Eclipse that allows you to do just that.

- If you are writing front-end web apps, use a tool like LiveReload which will refresh your browser page automatically.

- Test or even run your code in REPLs as is commonly done in Lisp, Scala, and Python environments.

If you're a senior developer, consider tracking and rating your developers on how they successfully take action on feedback. Also, don't forget that making feedback public can help your team build trust and encourage members to push their limits.

Whatever the situation, what you need to keep in mind is that there should be as little friction as possible between trying out an idea and seeing the results of it.

Ask yourself:

- Do you regularly receive and give feedback to your team members?

- Do you consciously set aside time to practice?

- Have you set up your environment so that feedback loops are kept as short as possible?

- Are you in the habit of writing fast automated tests?

6. Reflect on your results

This step is primordial. Nothing kills progress as much as working on auto-pilot and stagnating on a plateau.

After seeing your results, you need to reflect on them by asking questions like:

- Why didn't it work on your previous attempts? Why does it work now when you tried this particular way?

- How will you apply the lessons learned in this practice session in the future? Can you write these into a ‘Lessons learned’ document and share it with the team?

- Did you notice anything in the process that you can improve? Is there anything that you can add to the Practice Plan?

Also, these tidbits from The Pragmatic Programmer can inspire you to find your own ideas:

- Don’t code blindfolded. If you don’t understand the technology or the application on which you’re working, focus on familiarising yourself with the basics first.

- Document your assumptions. The Design by Contract allows you to do just that; so, consider giving it a try.

- Don’t be a slave to history; i.e. don’t let existing code dictate future code. If there’s code that needs to be yanked or refactored, be bold about it and make the changes required.

Like Clean Code, I highly recommend that you read The Pragmatic Programmer too. Mr. Sonmez also agrees that this book is a must-read. Read his review about it here.

7. Apply the law of ‘the vital few’

This law, more commonly known as the Pareto Principle, essentially means that there is a small subset of all activities that yield the lion’s share of output.

This idea can be especially useful when you’re optimizing for performance (e.g by identifying the methods that are taking up the most resources in your application), but it’s also useful for your practice plan.

Do this in three steps:

- Identify the things that create the most value. When you’re just getting started on the project, these should be the things that you have identified in your Practice Plan. As you get more and more experienced, they could be a lot of other things. Identify some pain points that your team is facing by asking questions like:

- Is there some area that is known to be regression-prone or hard to maintain?

- Can I simplify the architecture in the most frequently used areas?

- Project goals change; so identify the new top priorities and follow the steps in this post again.

- Practice them repeatedly. The key here is to repeat this as often as possible until you feel comfortable with it.

- After every few iterations, identify and remove the things that create the least value, add the things that bring the biggest returns, and repeat.

Ask yourself:

- Where does your team need help the most right now?

- In which areas are issues most commonly reported?

- What parts of the source code are known to cause maintainability issues?

Your next steps

I’ve summarized the seven steps in a flow chart for you:

You'll notice from the key above that there is a central theme: being mindful about the craft. Don't forget there is a ‘deliberate' in ‘deliberate practice.' Observe and extract the principles every step along the way.

In the same way as traveling without direction will get you to nowhere land, practicing without intentionality will cause you to perform without it.

Take action. Seeing yourself improve will inspire you to believe in deliberate practice even more. So, don't leave practice to chance, practice and work deliberately.

Information alone won’t help

If you already knew some of these ideas, don’t go out looking for the shiny new tactic.

You don't have to follow all the advice on deliberate practice out there (in fact, you shouldn't try to). Just follow a simple framework and you'll be fine.

As you get more at ease with practicing deliberately, you’ll have the opportunity to make changes to it and make it work best for you.

Taking this even further

Think of what parts of your work can be systemized.

Other recommended resources

- Some developers like to practice with “katas,” whereby they work on problems that exercise skills in specific areas. One site that has katas is codekata.com.

- If you would like to hear the “devil’s advocate” view, John has some mixed feelings about it. Watch what he has to say on the subject.

- Mastery by Robert Greene is one of my favourite books that examines the subject in depth.

- The Passionate Programmer by Chad Fowler. The title states clearly to whom it’s targeted :) Highly recommended.

- Make It Stick by Peter Brown. Research-backed book from which I learned a lot about learning.

To give other readers some ideas on how to take action, do share examples in the comments on how you'll apply this to your work. I can’t wait to see what you think of!

You can also check out my course “10 Steps to Learn Anything Quickly” for methods to optimize your learning.

5. Incorporate feedback

5. Incorporate feedback