There is something you need to know about me.

I’m a huge fan of continuous integration.

If you put me on a new software development team and you don’t already have an automated build process and continuous integration set up, you can pretty much bet that the first thing I am going to do is get all of that going.

I love the idea of automation.

I love making things more efficient and automatic, whenever possible.

To me, that is what continuous integration represents.

It’s taking that slow, painful, tedious, and error prone process of building the software, running tests against it, getting it packaged up to be deployed, and making it automatic.

But it’s much more than that.

Continuous integration, or CI as it’s usually called, is also about increasing the frequency in which code that individual developers are working on is merged together, so you don’t end up in the kind of merge hell I mentioned in the chapters on source control quite as often.

The sooner you are able to integrate, the less chance for integration hell and the faster you will find integration issues.

And finally, continuous integration provides the whole team with feedback—and fast.

When you are able to check in some code and know in two minutes whether that code compiles and whether you broke something in five—all while seeing the results in one central location—you’ve got a very fast and useful feedback cycle.

The faster the feedback cycle, the faster software can evolve, and the more the overall quality can be improved—an extremely important element in Agile development.

At this point, you may be thinking, “Yeah, John, it really sounds like you are trying to sell me this thing called CI, but what exactly is it?

I mean, it sounds good and all.

I like automation. I like feedback. I don’t think I’d like integration hell.

“But what exactly is this CI you speak of?”

Well, I think the best way for you to understand continuous integration is for me to take you back in time to show you how things used to be done and how continuous integration evolved over time. Then, I’ll finally take you through the workflow of a modern software development environment with a good CI system up and running.

Let’s begin the journey, shall we?

How Building Code Used to Work

I’m not super old, but I’m old enough to have built software in a time before there were fancy tools for automating it.

Early in my career—we are talking like early 2000s—it was pretty normal to work on a software development team where every single developer was responsible for figuring out how to create their own build of the software.

What do I mean by this?

Well, in any sufficiently large application, there are going to be quite a few components that may go into the build of the software being worked on.

There are of course going to be a large amount of source code files which must be compiled.

Often, there will be some other resources like external libraries which will need to exist on a developer’s machine to build the final software solution.

And there may be additional steps involved before or after the code is compiled to get the finished product.

It used to be that when you worked as a developer, you’d get a copy of the source code. Some guru who had been working on the software for the last five years would show you the magical incantations you needed to do to build the software, and then you were on your own.

Individual developers developed their own ways of getting the software build on their machines.

When it was time to produce a build that was ready to be tested or deployed out to customers, one of the developers would sacrifice chickens, walk backwards in a circle, light candles around a pentagram, hit CTRL+SHIFT+F5, and out would pop a finished version of the software.

There were a few big problems with this way of developing and building software, though.

The biggest one was that since each developer was building the software on their own machines—and in slightly different ways—there was a huge chance that two developers with identical versions of the code could produce two completely different versions of the software.

How could this be, you might ask?

Plenty of things can go wrong when you don’t have consistency, and everyone is following their own process of doing something.

Developers could have different versions of external libraries installed on their machines.

Developers could think they have the same source code, but actually forget to get the latest files from source control or had a local change made to a file, which they didn’t realize and that prevented the code from being updated.

The file or folder structure could be different, and that in turn could cause differences in how the software actually runs.

Plenty of things could go wrong.

The other major problem was that since developers were all building locally, if someone checked in some code that didn’t even compile, no one would find out until they pulled down that code and tried to build the software.

This might not seem like a huge deal, but it gets really fun when multiple developers check in bad code over a period of days or even weeks, and then when someone finally tries to build everything and finds out it’s broken, they have no idea what change or changes caused the issues.

Plus, I’ve worked at places where it literally took hours to just create a single build of the software.

Nothing worse than running a build on your machine for 4-5 hours and then finding out it’s broken.

Then Build Servers Came Along

One of the early ways to solve these kinds of problems was the introduction of builder servers.

The idea was that instead of having every developer build the software on their own machine, there would be one central build server, which was configured correctly and had all the right versions of the libraries, etc.

A developer could kick off a build on the build server, or the build server would automatically build the software every night.

At first, this started out as weekly builds.

So, you’d at least have some official weekly build of the software that combined all the changes from all the developers from that week together and was built in a uniform way.

One issue with the weekly build, though, was that often—especially with large teams—there would be an integration hell problem when trying to get that weekly build created.

Often, there would be a developer or IT person in charge of getting that weekly build to work, and they’d manually fix all the issues that were breaking the build and hunt down developers with conflicting changes to try and resolve them.

An improvement over no build server, but not by much.

Eventually, the idea of nightly builds became popular.

The idea was that if we integrated the code daily with the build server creating a new build every night, there would be less time for big issues to pile up and compound, and we could catch problems much earlier.

At first, this idea seemed crazy.

You wouldn’t believe the amount of resistance I got the first time I ever suggested a nightly build at one of the companies I worked for.

But, eventually it became the norm, and it did solve quite a few problems.

Nightly builds from a central build server helped get everyone synced up and on the same page, so to speak, and if the nightly build broke, it was everyone’s top priority to get it working again.

The idea of a nightly build pushed forward the need for actual automation of the build process itself.

This was very good.

In order to consistently build the software each night, we needed some automated way to get all the code together, compile it, and do any of the other steps required to create a working build.

This was the era of many scripts which were created in order to automate the process of building the software, at least on the build machine. It was still quite normal for developers to still have their own local build processes.

Makefile scripts, which used to only compile the code, started to become more sophisticated to handle the full build process for a build server, and XML-based build automation tools like Ant were created and became popular.

Life was getting good, but there were still major problems.

As Agile was becoming more and more popular, and the idea of unit testing was gaining support, nightly builds that just compiled the code and packaged it up were not quite good enough.

We needed shorter feedback cycles.

The whole team could get derailed if someone checked in bad code, and we didn’t find out about it until the next morning.

We needed some way to build the code, reliably, multiple times per day and to run some other code quality checks besides just “it compiles.”

Finally, Continuous Integration

Nightly builds were a difficult pitch, but nothing compared to trying to get management to buy into continuous integration, or the idea of building the software every single time someone checked in new code.

Why would you want to do that? We have nightly builds.

I don’t understand; you want to continuously build the code?

Wait a minute, let me get this straight. You want me to tell all the developers they need to check in their code multiple times a day? Are you kidding me?

There was a good amount of resistance, but slowly it was overcome as Agile became more popular. Continuous integration wasn’t just a nice dream, but rather a must-have in order to actually have short enough feedback cycles to get work items completed on each iteration.

The major problem, though, was how to do this.

How could we actually build the code every time new code was checked into source control?

The answer was continuous integration servers.

Specific software was developed that could be run on a build server, had the capability to detect source control changes, pull down the latest code, and run a build.

Pretty soon, developers were working to reduce the build time of code bases, so that the feedback could be even faster.

Now that we had this capability, it made sense to do more than just build the code.

Continuous integration evolved to incorporate running unit tests, and running code quality metrics like static code analyzers, which were all kicked off by an initial check in.

The biggest hurdle was—and still is for the most part—getting developers to check in their code early and often, so that we can get feedback fairly quickly.

Now, with CI in place, we can not only know within minutes whether a code change prevents the whole project from compiling, but also we can find out if any units tests were broken or even do things like run automated regression tests automatically to look for regressions.

Ah, life is good.

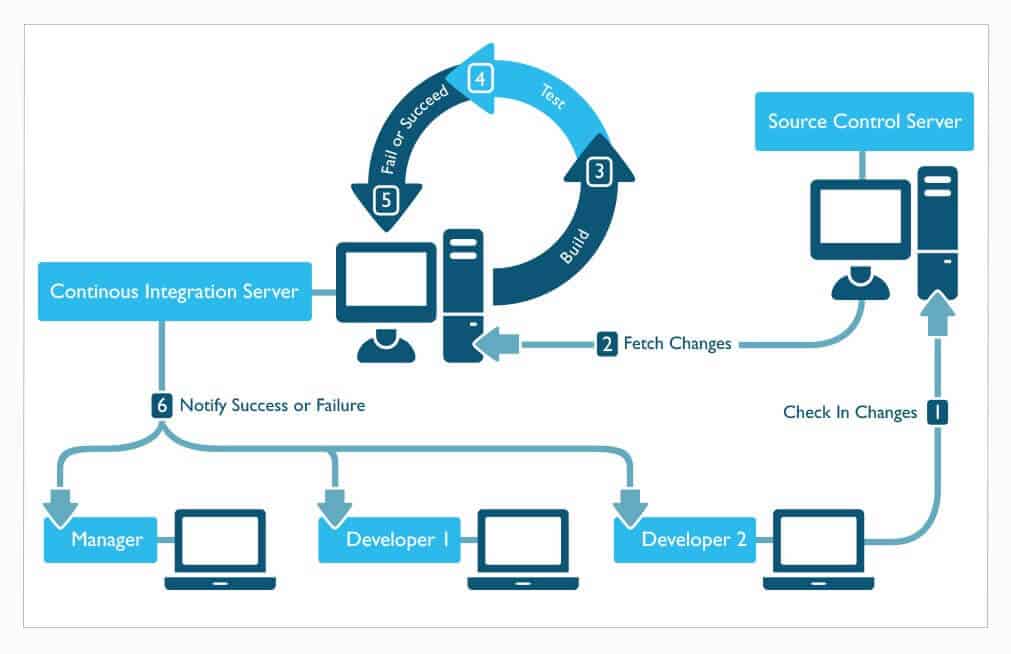

A Sample Continuous Integration Workflow

Ok, so at this point, you probably have a decent idea of what continuous integration is by hearing about the problems it solved and how it evolved.

But you still might not quite “get it”—and that’s ok.

Let’s walk through a sample workflow using continuous integration, and then maybe it will click a little better.

Check in code

The cycle starts with you checking in your code.

Of course, you’ve run the build on your local machine and run all the unit tests before you dare check in code to the main repository and risk breaking the build for everyone… right?

New build is kicked off

The CI software sitting on the build server just detected a change to the source control branch it’s monitoring.

It’s your code! Oh goody!

The CI server kicks off a new build job.

Code is checked out

The first thing the new build job does is to get the latest changes.

It pulls down your code changes—and any other ones on the branch—and puts them into its working directory.

Code is compiled

At this point, a build script of some sort is usually kicked off to actually compile and build the code.

The build script will run the commands to build the source code.

It will also link in any external libraries or anything else needed to compile the code.

If the code fails to compile, the build will stop right here, and an error will be reported.

This is called breaking the build—and it’s bad.

I thought you said you compiled the code on your machine before checking it in?

Shame!

Static analyzers are run

Assuming the code built correctly, static analyzers are run to measure certain code quality metrics.

If you don’t know what these are, that’s ok.

Basically, they are tools that can take a look at the code and look for possible errors or violations of best practices.

The results from these analyzers are stored to be reported when the build is finished.

Some builds can actually be set to fail if some threshold is not met for a code quality metric derived from the static analyzer.

Unit tests are run

Assuming everything is still good, the CI job kicks off the unit tests.

The unit tests are run against the compiled code, and the results are recorded for later.

Usually if any unit tests fail, this causes the whole build to fail. I highly recommend this approach.

Results are reported

Finally, the results of the actual build are reported.

The report will contain data about whether the build passed or failed, how long it took to run, code quality metrics, unit tests run, and any other relevant data.

Documentation might also be auto-generated by the build at this point as well.

The results can be set up to be emailed out to the team—especially in the case of a failure—and most CI software programs have a web interface as well where anyone can see the results of the latest build.

Software is packaged

Now the build software is packaged up into a form where it can be deployed or installed.

This usually involves taking the compiled code and any external resources or dependencies and packaging it up into whatever structure is necessary to have a deployable or installable unit.

For example, a file structure might be created that contains all the right files, and then the whole thing might be zipped up.

At this point, the build job may also apply some kind of tagging in source control to mark the version of the software.

Code is optionally deployed (continuous deployment)

This last step is optional—actually, I suppose that the previous step is optional as well.

But more teams are doing continuous deployment where they deploy the code directly into an environment for it to be tested—or, if they are really brave, right into production.

Finished

And that’s it.

There are some variations in these steps, of course, and there may be some additional steps, but the basic idea is to build the code, check for problems, and get the code ready for deployment all automatically whenever new code is checked in.

This allows us to be able to know very quickly if a new change to the system caused an error, so that it can be fixed right away.

Even though I’ve breezed over all of this, I don’t want to make it sound too simple.

Build engineers can spend quite a bit of time constructing a well-oiled continuous integration process, and there are all kinds of debates about how it should be done and what are the best practices for doing it.

CI Servers and Software

One critical component of continuous integration is CI software.

Without CI software, we’d have to write custom scripts and essentially program our own build servers.

Fortunately, many smart developers quickly realized the value of building CI software, which helps to automate most of the common tasks of continuous integration.

Most CI software works in a very similar manner, making it easy—or at least easier—to implement a workflow like the one I described above.

There are actually quite a few CI servers and software available, but I’m only going to highlight a few here that I have found to be the most commonly used at the time of writing this book.

Jenkins

Jenkins is pretty much my “go to” CI software.

It’s a Java program which was initially created to do CI in Java environments, but it’s become so popular and is so easy to use that it has expanded to become usable for just about any technology.

Jenkins is extremely easy to install and get running as it contains its own built-in webserver.

It also has a ton of plugins.

If you are trying to do something in Jenkins, there is a good chance someone has written a plugin to do it for you. That is one of the main reasons why I like and use Jenkins so much.

(I actually have a Pluralsight course that talks you through the Jenkins basics.)

Hudson

I’m going to spare you the drama of the big long ass story about the Hudson / Jenkins split and give you the short of it.

Before Jenkins came along, there was Hudson.

There were some fights, Jenkins split off from Hudson, and Hudson continued to be developed on its own.

Hudson is controlled by Oracle, and I personally don’t think it’s as good as Jenkins, since the creator of Hudson, Kohsuke Kawaguchi, and most of the original Hudson team, moved to Jenkins.

Honestly, I don’t know if Hudson is still alive and being worked on.

Travis CI

Travis is another popular CI software, but it operates a little bit differently.

Travis CI is actually hosted and is provided as a service.

In other words, you don’t install Travis CI; you sign up for it.

It’s really designed to perform CI for projects hosted on GitHub.

Travis is gaining popularity since many projects are hosted in GitHub, and it’s well-designed and easy to use.

Plus, it’s nice to not have to maintain your own build server.

TFS

If you are working exclusively in a Microsoft shop, TFS (Team Foundation Server) does offer continuous integration support, but in my experience, it’s pretty simplified and isn’t robust enough to compete with some of the other, more popular offerings.

But, I suppose if you want something simple—and it has to be a Microsoft solution—this one could work for you.

TeamCity

TeamCity is another popular continuous integration server, which is created by the commercial company JetBrains.

It has a free version, but it is also a licensed product.

So, if you are looking for something with a little more professional support, this is a good option.

Many .NET teams use TeamCity for their CI needs.

More?

I’ve only given you a small sampling of some of the more popular options for CI servers, but there are quite a few in existence.

Check out this near complete and updated list if you want to see all the options.