Welcome to Part Eleven of our journey through time, learning how the Internet has evolved and studying the effect it has had on our lives.

In the series so far, we have focused on the Internet innovations that have come from Microsoft, Netscape, Sun Microsystems, MySpace, Yahoo, Facebook, and Google. This has largely missed the contributions of one of our industry’s greatest companies, Apple Computers, and so we must redress that right now.

It is impossible to cover the history of Apple Computers without mentioning Steve Jobs, the savior of the company that he co-founded and loved dearly. This article discusses how he spectacularly turned the company around, from an aimless enterprise free-falling toward bankruptcy to one of the most highly motivated and successful companies in the world.

I hope that this gives you inspiration for one of the most important rules in business: sharply focusing on the essential needs of your business and your customers.

Sculley and Jobs

Jobs was the co-founder and CEO of Apple Computer, Inc., and soon he gave the CEO role to seasoned businessman and angel investor Mike Markkula. Then, after two years of working long hours, Markkula’s wife insisted that he find a replacement and spend more time with the family again.

Jobs and Markkula agreed that Jobs was not yet ready to run the company, and Jobs courted Pepsi boss John Sculley for this role. Sculley admitted that he was “smitten” with Jobs, and Jobs was absolutely thrilled when Sculley agreed to take the top job. This “honeymoon” lasted for less than two years.

In May 1984, Jobs helped arrange a surprise party for Sculley for his one-year anniversary at Apple and praised him:

“The happiest two days for me were when Macintosh shipped and when John Sculley agreed to join Apple. This has been the greatest year I’ve ever had in my whole life, because I’ve learned so much from John.”

By 1985, reality began to bite hard. Many of the top engineers, including co-founder Steve Wozniak, quit the company. Wozniak even told a reporter, “Apple’s direction has been horrendously wrong for five years.”

Sales of the Macintosh failed to meet expectations. Sculley and Jobs began disagreeing more frequently over more and more aspects of the business. Jobs hated Sculley’s lack of passion for product excellence, and Sculley grew frustrated with Jobs’s rude and selfish attitude.

Sculley told Jobs, “We have developed a great friendship with each other, but I have lost confidence in your ability to run the Macintosh division.” Jobs moaned that Sculley knew nothing about computers and was doing a terrible job.

Jobs began plotting to get Sculley removed, and Sculley told the board he wanted Jobs to step down. The board met with both of them privately, and sided with Sculley. At Jobs’s request, Sculley agreed that the transition would occur slowly over the next few months.

Showdown

Jobs did not honor this agreement; instead, he planned a coup to oust Sculley. This treachery backfired on Jobs, as Sculley was informed of this plan and raised it at the next board meeting. “It’s come to my attention that you’d like to throw me out of the company. I’d like to know if that’s true.” Jobs replied, “I think you’re bad for Apple, and I think you’re the wrong person to run the company.”

Sculley raised the stakes, declaring to the rest of the board, “It’s me or Steve—who do you vote for?” The board backed Sculley. “I guess I know where things stand,” said Jobs, leaving the room.

Both Jobs and Sculley considered resigning from the company after this meeting, but both changed their minds quickly. Over the next few days, the board formed a reorganization plan, and Sculley informed Jobs he was no longer in control of the Macintosh division but could stay on as board chairman.

Three months later, Jobs announced that he planned to start a new company. This company was NeXT.

Post-Jobs Lull

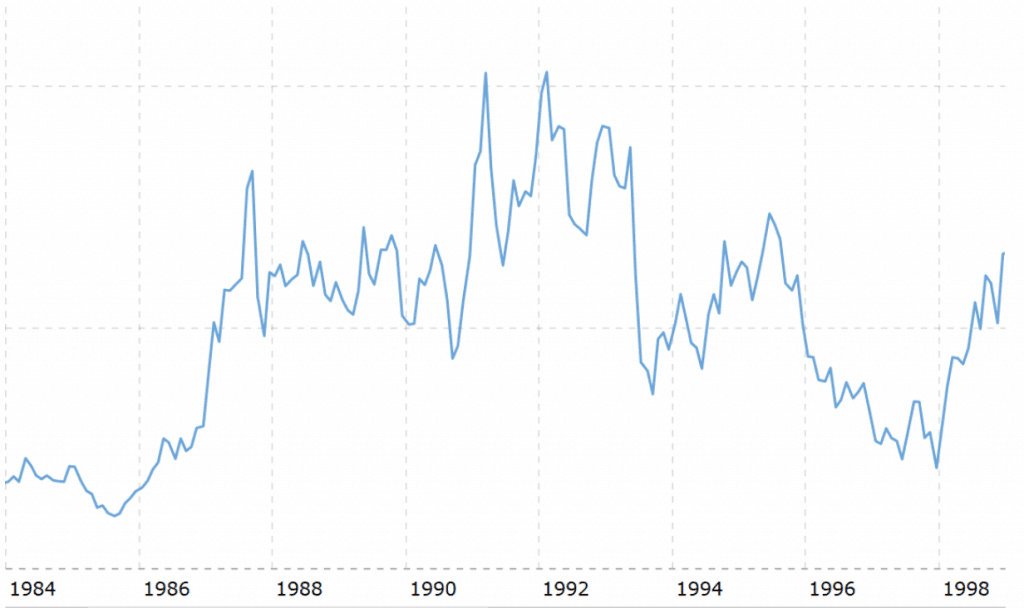

Apple made some recoveries to its business over the next couple of years after Jobs left, but it ran into trouble again by 1988. During the early to mid 1990s, Apple’s market share steadily declined. Its poor performance precipitated the departures of John Sculley and his successor, Michael Spindler, from Apple Computer, Inc.

Gil Amelio became the new CEO in February 1996, but was unable to turn the company around either. Within one year of Amelio’s appointment, Apple had lost $1 billion.

Jobs first met Amelio in 1994 and asked for Amelio’s help in reinstating him as CEO of Apple, boasting, “There’s only one person who can rally the Apple troops.” Amelio was unimpressed and unceremoniously shooed Jobs out of his office.

However, not long after Amelio became CEO, he realized that Apple had major problems with the operating system it was developing. He publicly promised that he would quickly find an alternative, and this meant he needed to partner with another company.

Amelio entered into negotiations with Jean-Louis Gasée to buy out Be Inc. Sensing real weakness from Amelio, Gasée kept overpricing his company, and after word got back to Amelio that Gasée had bragged, “I’ve got them by the balls, and I’m going to squeeze until it hurts,” Amelio decided to seriously consider other options.

These options included Sun’s Solaris operating system, Microsoft Windows NT, and the NeXTSTEP operating system.

By late 1996, NeXT was in even worse financial trouble than Apple. After hearing that Apple was looking to invest in a new operating system, Jobs called the Apple CEO, and Amelio agreed that Jobs should come and pitch to them.

The Return of Jobs

When Jobs pitched to Apple, he suggested that Apple buy not just the software, but his entire company. Amelio invited both NeXT and Be to give final presentations to Apple. Jobs gave a sales pitch which Amelio described as “dazzling” and it was shortly agreed that Apple would buy out NeXT.

On the same day as the financial negotiations were made, Jobs suggested that he should have a seat on the Apple board. Although Amelio initially refused, Jobs laid on the charm until Amelio agreed to go along with his idea.

When Bill Gates was told that Apple would not be investing in Microsoft, and instead buying out NeXT, he was livid. But years later, when Gates reflected on Amelio’s decision, he said, “What they ended up buying was a guy who most people would not have predicted would be a great CEO, because he didn’t have much experience at it, but he was a brilliant guy with great design taste and great engineering taste.”

Amelio organized a press event and announced that Steve Jobs would be returning as a part-time advisor.

Jobs’s first keynote presentation was MacWorld San Francisco in January 1997. He immediately set himself apart from Gil Amelio in terms of his presentation skills and was given a hero’s welcome from the crowd. The Wall Street Journal exclaimed, “The return of Elvis would not have provoked a bigger sensation.”

Jobs’s main influence in the early days was to put his best engineers from NeXT into some of the top positions at Apple, including Avie Tevanian as senior vice president of software engineering, and Jon Rubinstein as senior vice president of hardware engineering.

Jobs also pressed Amelio to kill Apple’s Personal Digital Assistant, the Apple Newton, although Amelio objected that this would cost the company a fortune.

Massacre of the Board

It was not long before the news media began speculating that Jobs might be scheming another takeover attempt. Although he did not say so publicly at the time, Jobs thought of Amelio as a “bozo” and privately bad-mouthed him, saying he was “the worst CEO I’ve ever seen, I think if you needed a license to be a CEO he wouldn’t get one.”

His good friend, Larry Ellison, increased tensions by telling reporters, “Steve’s the only one who can save Apple.” Jobs refused to confirm or deny these rumors.

After more financial woes, the board seemed to agree on Jobs’s dim view of Amelio, and asked him if he would take over as CEO, but Jobs was already CEO of Pixar, and he was torn on the idea. He declined, but agreed to be more active with Apple for the next 90 days while they looked for a new CEO.

Jobs pushed the board hard on repricing the top employees’ stock options in order to incentivize the best employees to keep working hard for Apple and turn its fortunes around. “It has to be done fast. We’re losing good people,” he argued. When the board objected, he threatened, “Guys, if you don’t want to do this, I’m not coming back on Monday.”

Apple chairman Ed Woolard called Jobs the next day and said, “We’re going to approve this, but some of the board members don’t like it. We feel like you’ve put a gun to our head.”

Rather than thanking the board, Jobs whined, “This company is in shambles, and I don’t have time to wet nurse the board. So I need all of you to resign. Or else I’m going to resign and not come back on Monday.” Ed Woolard was excluded from this demand.

The board did not actually need much persuading to resign, and agreed to elect Jobs to the board. Jobs hired Larry Ellison as his first board member, followed by Bill Campbell and Jerry York.

Microsoft Partnership

Realizing that Microsoft was vital for Apple’s survival, Jobs called up Gates and said, “I need help.” He asked for a commitment from Microsoft to keep developing applications on the Macintosh, and a $150-million investment in Apple. In return, Apple dropped its ongoing patent lawsuit against Microsoft and agreed to promote Internet Explorer on the Mac.

The announcement was made by Jobs in August 1997 at MacWorld Boston, with Bill Gates appearing via satellite link to a shocked crowd of 5,000 Apple fans. Jobs later regretted the supersized Gates presentation, claiming it was his “worst and stupidest staging event ever.”

Gates concurred, “I didn’t know that my face was going to be blown up to looming proportions.”

The next month, Jobs announced he was taking over the title of interim CEO from Fred Anderson. To demonstrate that the company meant much more to him than just a salary, he gave himself only $1 per year in salary with no stock options. He joked, “I make 50 cents for showing up, and the other 50 cents is based on performance.”

The board continued to look for a new CEO for a few more months, and then quietly abandoned the search. Jobs concluded, “Apple was in no shape to attract anybody good.”

Simplicity: The Art of Work Not Done

One of the most important principles for a successful business is the “Hedgehog Concept.”

Its name originates from the Greek poet Archilochus, who wrote, “The fox knows many things but the hedgehog knows one great thing.” The idea is to forget about the many things and focus on the one great thing.

Consider the following three questions:

- What lights your fire?

- What could you be best in the world at?

- What makes you money?

Whatever work intersects all three of these answers is the work that you should focus on. Eliminate everything else. For further details on this idea, see the business classic Good to Great, by Jim C. Collins.

Jobs was a master of the Hedgehog Concept, especially after his return to Apple.

The previous CEO, Gil Amelio, had kept asking employees to create more products, and by the time Jobs seized power, there were a dozen different versions of the Macintosh. None of them particularly stood out from any of the others.

Jobs couldn’t understand it at all, and when he asked his staff, “Which ones do I tell my friends to buy?” he couldn’t get a straight answer.

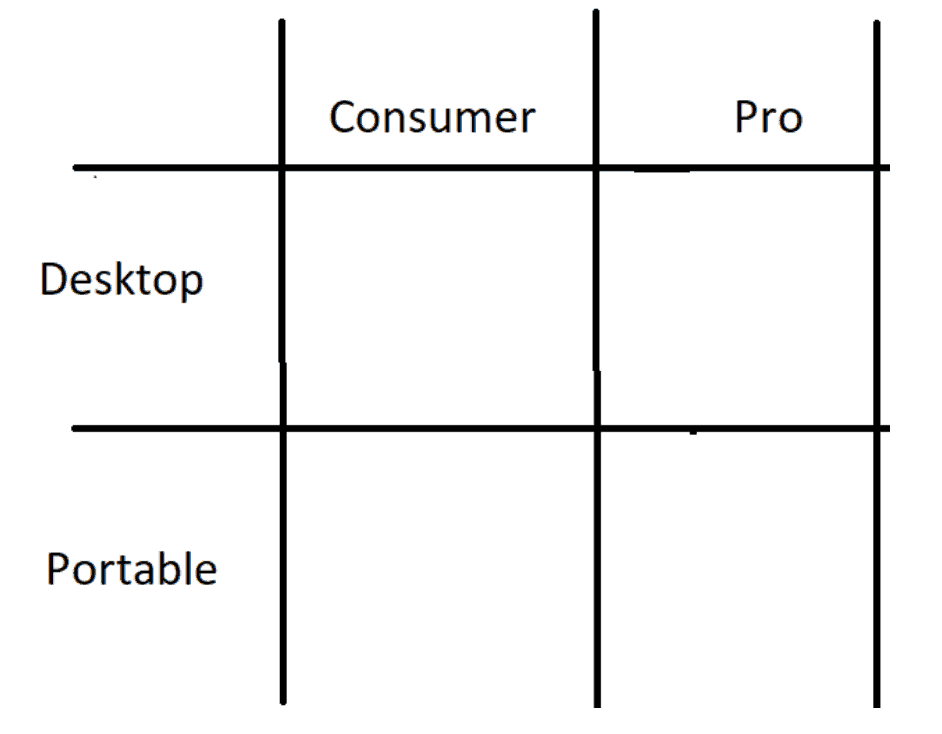

He drew a four-squared chart on a whiteboard like this:

From then on, the company was only allowed to make four products—four great products. The best possible product that could be made in each category.

Jobs insisted that the company always had a sharp focus, but he also demanded the highest levels of quality: “If something isn’t right, you can’t just ignore it and say you’ll fix it later. That’s what other companies do.”

For regular consumers wanting a desktop, Apple launched the iMac.

Consumers looking for a laptop were offered the iBook.

For high-end professionals, Apple offered the Power Macintosh G3.

And for professionals looking for a powerful computer on the move, there was the PowerBook G3.

For the iMac and iBook, and many subsequent products, the “i” was used to signify the integration of Internet features within the products.

Jobs also insisted that Apple’s marketing was simplified and streamlined. As Jobs took over, there were more than a dozen different advertising campaigns running, but they failed to deliver a consistent message.

Perhaps Apple’s most iconic television commercial is “1984,” where Apple was characterized as the hero rebelling against the tyranny of Big Brother (who viewers easily identified as IBM). The minds behind this commercial were the Chiat/Day agency, and Jobs never forgot the impact it made when he launched the original Macintosh.

After Michael Spindler became CEO, he replaced Chiat/Day with agency BBDO. A few years later, when Apple was in severe financial trouble, BBDO pitched the slogan, “We're back,” but Jobs hated this idea. He reasoned, “The slogan was stupid because Apple wasn't back.”

Jobs called Chiat/Day, and they pitched their latest idea, “Think different.” Rather than featuring any of the products themselves, this commercial celebrated what creative people could do using computers.

Jobs thought this concept was “10 times better than anything the other agencies showed,” and he got so emotional during the pitch that he started to cry.

The tough side of this new focused approach was many Apple employees were laid off. Jobs culled more than 3,000 jobs in his first year back. But if he had he not done this, the whole company would most likely have gone bankrupt.

Craft and Design

Jobs wanted to bring in a world-class designer to add flair to Apple’s products. But as he got to know the head of Apple’s design department, he began to realize that he might already have one.

Jonathan “Jony” Ive had been head of the design department since 1996, but felt stifled under Amelio: “All they wanted from us designers was a model of what something was supposed to look like on the outside, and then engineers would make it as cheap as possible. I was about to quit.” Hearing Jobs talk about the goal of making great products changed his outlook, and he decided to stay on at Apple.

Ive is a fan of Dieter Rams, the industrial designer who rose to fame with a “less but better” approach. Jobs was also highly passionate about this and hated anything that was more complex than it needed to be.

Jobs insisted that product design must drive the engineering rather than vice versa, as it had been under the previous Apple CEOs.

By 2000, it was clear that Apple had been turned around. Jobs finally decided to drop the word “interim” from his job title and become permanent CEO.

Right at the end of Macworld 2000 in San Francisco, Jobs announced this to a rapturous standing ovation. However, he finished by saying he liked the title iCEO because it reminded him of how important the Internet would be to Apple’s future.

For Apple’s dramatic turnaround, the board agreed to reward Jobs with his own airplane: a Gulfstream V. Jobs was far too impatient and demanding to cope well with commercial airlines and had been renting Larry Ellison’s private plane.

However, deciding on its design was something of a poisoned chalice for him: he fretted for more than a year over the many small details of how his airplane interior should look.

Proving the Critics Wrong

One of the difficulties that Apple faced was its products were generally more expensive than its competitors, and the retailers did not have much incentive to promote Apple’s products over any other sale it could make.

Jobs had the idea of opening up his own stores, exclusively selling Apple products, and worked closely with Ron Johnson and Bohlin Cywinski Jackson to make it happen.

One week before Apple was due to open its debut store in Tysons Corner, Virginia, Cliff Edwards wrote, “Sorry Steve, Here's Why Apple Stores Won't Work.” This article explained Jobs’s “perfectionist attention to aesthetics has resulted in beautiful but pricey products with limited appeal outside the faithful: Apple’s market share is a measly 2.8 percent.”

Conventional wisdom indicated that the new stores were likely to attract existing Apple fans, while almost everyone else carried on purchasing cheaper products from regular computer stores.

David A. Goldstein, president of researcher Channel Marketing Corp., predicted the high cost of renting retail space and construction would be higher than its profits from sales at the new stores: “I give them two years before they're turning out the lights on a very painful and expensive mistake.”

The skeptics made the mistake of underestimating the strong and growing appeal of the Apple brand. When the first store opened in May 2001, fans queued just to get into the store. Demand would only grow stronger as Apple launched better products.

As new venues opened, many fans queued overnight for the privilege of being some of the first people to experience the store. There are now hundreds of stores located all around the world.

Dot-Com Crash

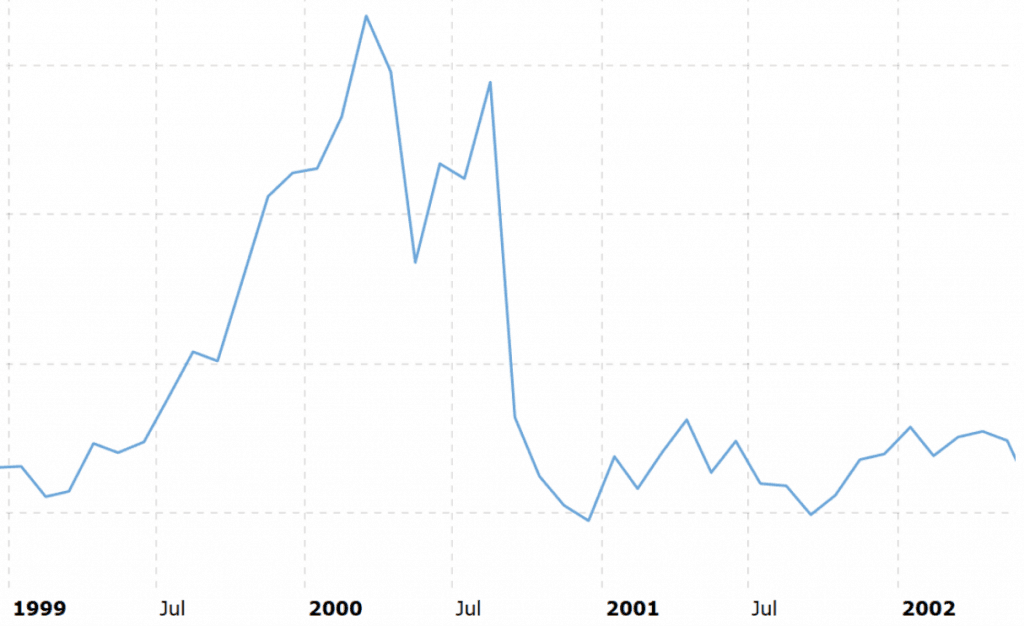

In Part Eight of our series, we learned that the dot-com crash hit Yahoo! hard but Google actually benefited from it. Apple Computers’ profits were also hit by the dot-com crash, and its share price nosedived in 2000.

In this period, industry analysts noted that sales of computers were generally falling. Newer models were gradually becoming less distinct from the computers that preceded them, and as many smaller Internet-enabled devices came into the market, these took market share away from desktop manufacturers.

The entire industry was at the beginning of a massive transition, one that brought great opportunities and threats. Any company that was slow to react faced possible extinction, while innovators could reap great rewards.

Jobs decided to reimagine the Macintosh as a digital hub for new devices that Apple and many other companies were developing. He recognized and unashamedly bragged that Apple was uniquely positioned in the market for delivering end-to-end solutions: “We’re the only company that owns the whole widget—the hardware, the software, and the operating system. We can take full responsibility for the user experience. We can do things that the other guys can’t do.”

In 2000, Apple found itself behind in the emerging computer music market. Apple bought out music software SoundJam and tasked its creators—Jeff Robbin, Dave Heller, and Bill Kincaid—with reworking it into an official Apple product: iTunes.

Digital Lifestyle

Forty-five minutes into Macworld 2001 in San Francisco, Jobs explained how the Internet had enhanced the computing experience, calling it the second age. He predicted a third age, which he dubbed “Digital Lifestyle”—an age of cell phones, portable CD and DVD players, MP3 players, and digital cameras and camcorders. He positioned the Macintosh as the “digital hub” of your digital lifestyle.

“So what are we going to focus on next?” Jobs asked the audience. He explained that users want to transfer their music CDs to MP3 format, create their own playlists, and burn them onto their own CD recordable discs.

Jobs plugged some competitor products—RealJukebox, MusicMatch, and Windows Media Player—and then criticized them for being too complex and having restrictions that were only lifted if you bought their pro versions. iTunes offered a simplified user interface and was given away for free to all Mac users.

Tokyo

In February 2001, Jobs presented another Macworld in Tokyo and introduced new iMac colors “Flower Power” and “Blue Dalmatian.”

Apple’s hardware chief, Rubinstein, was also in Japan visiting Toshiba, where he discovered they were developing an ultra-thin 1.8-inch drive which stored 5GB. This was exactly the new technology that Jobs had asked him to look for.

Rubinstein met up with Jobs that night and said, “I know how to do it now. All I need is a $10-million check.” Jobs didn’t even need to think about it; he knew that they were onto something really big.

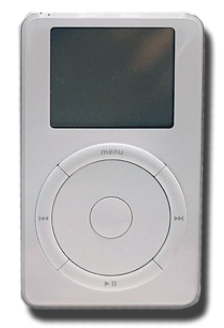

Rubinstein employed Tony Fadell to work on their new portable MP3 player, and Fadell quickly created the concept and initial design. Phil Schiller added the idea of a trackwheel for scrolling through songs quickly. Jobs simplified the design in many areas and insisted that the team remove the on-off switch. Jony Ive argued that the color of the device, the headphones, and the power supply should all be pure white.

Apple Special Event: iPod

On Oct. 23, 2001, Jobs presented a special event to the press in Cupertino with the event invitation tagline: “Hint: It's not a Mac.” He announced that Apple was launching the iPod, that it held 1,000 songs, had 20 minutes of skip protection, used Apple’s FireWire technology for transferring songs quickly, and had up to 10 hours of battery life.

He raised the point that the iBook already played songs and was portable, but the iPod was ultra-portable as it was the size of a pack of cards and lighter than most cell phones. He described the scroll wheel as another breakthrough enabling quick navigation.

The iPod was designed to work with iTunes, which was only initially available for the Macintosh. A Windows version of the iPod was released later, although Jobs himself was very reluctant to support his rival’s operating system.

Jobs’s initial position was that Windows users would be supported “over my dead body,” but after his top executives proved to him that doing this made great business sense, Jobs pushed his team to make iTunes available for Windows as well.

iTunes Store

At the beginning of the 21st century, music piracy was rife, with Napster and many other peer-to-peer software services enabling users to share copyrighted music.

The record companies were in disarray over how to combat this threat to their business. They launched many lawsuits against piracy, but struggled to agree on any commercial solution for the rise in digital music.

Jobs wanted to support the music industry against piracy and said, “We believe that 80 percent of the people stealing stuff don’t want to be,” but he found persuading the top record companies to allow digital versions of their music to be surprisingly difficult. Jobs recalled, “I’ve never spent so much time trying to convince people to do the right thing for themselves.”

Macintosh’s small share of the market was an advantage to Apple here because it allowed Jobs to argue that the record companies could pilot the idea on a small scale with them.

The biggest disagreement was whether to allow songs to be sold individually or to only sell entire albums. There are artistic reasons why some musicians don’t like to sell songs individually, but Jobs argued that people were already pirating songs individually and that selling songs individually was the only way to compete with piracy.

Jobs met with many of the major artists to persuade them to allow their songs to be sold on the iTunes store. After seeing how well the iTunes store worked with the iPod, Dr. Dre remarked, “Man, somebody finally got it right!”

After deciding to support Windows, Apple went back to the record companies to renegotiate the contracts, as they had only initially agreed to make their music available on the Macintosh.

Although Sony, who had a rival online music service called Pressplay, were unhappy with Jobs for changing the terms so soon after a deal had been made, the other record companies could see that the iPod was highly successful and signed the new contracts. This pressured Sony into signing as well.

On April 28, 2003, Jobs hosted another special event with several announcements. The first of these was the third-generation iPods with 10, 15, and 30GB of space and a dock connector, allowing for FireWire or USB connectivity.

He also spoke about new features in iTunes version 4, such as support for Advanced Audio Coding, which sounds better than MP3-encoded songs at the same bitrates, and allowing album artwork to be dragged into iTunes.

Then he spoke about Napster as a phenomenon, but stressed that downloading music from it was stealing. He said the reason it had proliferated was because there was no legal alternative.

A couple of exceptions to this were the Pressplay and Rhapsody subscription-based services. Jobs slammed his competitors’ products, saying, “These services treat you like a criminal.”

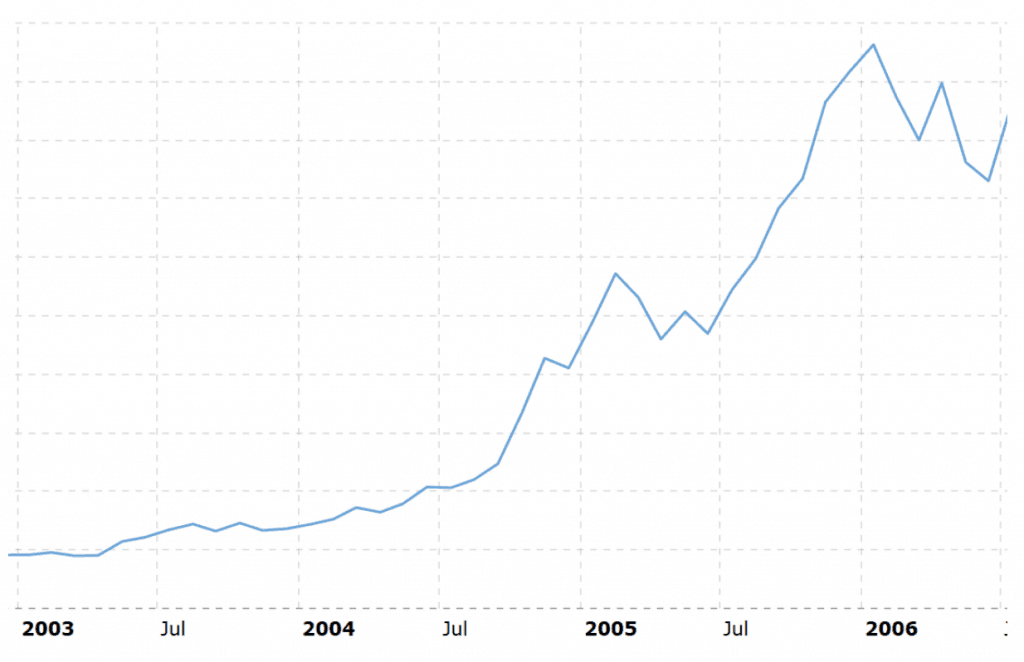

The iTunes Music Stores launched with 200,000 songs available for download. It sold a million songs within the first six days. Over at Microsoft, Bill Gates was stunned and admitted to his colleagues that “Jobs has us a bit flat-footed again,” but pledged that Microsoft would launch a better product than Apple had.

They never did. In fact, nobody did. Sony also launched Sony Connect in 2004 to compete with the iTunes Store, but it was a failure. Microsoft released the Zune music player in 2006, but it never achieved the popularity that the iPod enjoyed.

By the time Microsoft launched the first Zune product, Apple had already launched the iPod Mini and the iPod Shuffle. iTunes Store user Alex Ostrovsky was pleasantly surprised to receive a congratulatory call from Steve Jobs after buying Coldplay’s “Speed of Sound.” He had downloaded the one-billionth song and was rewarded with 10 iPods, an iMac, and a $10,000 music gift certificate.

Conclusion

The massive success of the iPod and the iTunes Store positioned Apple as one of the biggest technology companies in the world. Quite an achievement for a company that was only 90 days from insolvency eight years earlier.

But Apple was not resting on its laurels. Instead, 1,000 employees were working flat out on an even more revolutionary product, codenamed “Project Purple.”

Join us in Part 12 for the story of the iPhone.