In Part 12, we covered the story of the development of the original iPhone up until the beginning of 2007. By this time, Apple CEO Steve Jobs was about to announce the iPhone, but development was still frantically underway, and the device was not nearly complete.

In Part 13, we learn how these problems were overcome and how Apple found its recipe for success.

At the start of the new year, Jobs began practicing for the iPhone launch at the Moscone Center in San Francisco. Even on the fifth day of rehearsals, the prototype phone was randomly dropping calls, losing internet connection, freezing, or shutting down. Senior engineer Andy Grignon took his share of Jobs’ fury as he dished out expletives and threatened, “If we fail, it will be because of you!”

Macworld 2007: The iPhone Reveal

Steve Jobs unveiled the iPhone at Macworld on January 8, 2007. As he had done for the launch of the iMac, Jobs invited back Andy Hertzfeld, Bill Atkinson, Steve Wozniak, and the 1984 Macintosh team to join in the celebrations.

Jobs teased his audience by eulogizing the rare products that change everything, and then he announced, “Today, we’re introducing revolutionary products of this class. The first one is a widescreen iPod with touch controls.” The audience erupted in applause.

“The second, is a revolutionary mobile phone.” Even bigger cheers thundered from the audience.

“And the third. Is a breakthrough, internet communications device.” The audience was rapt.

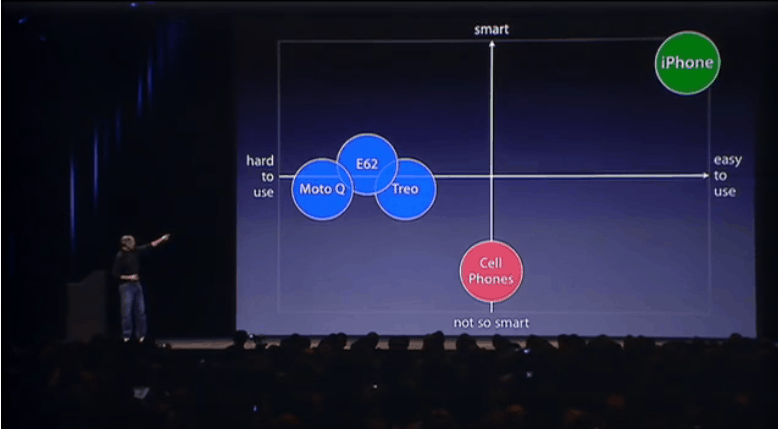

“Are you getting it? These are not three separate devices, this is one device. And we are calling it iPhone.” Jobs went on to observe how other smartphones on the market were either not very smart or not very easy to use and claimed the team was building a phone much smarter and easier to use than anything else.

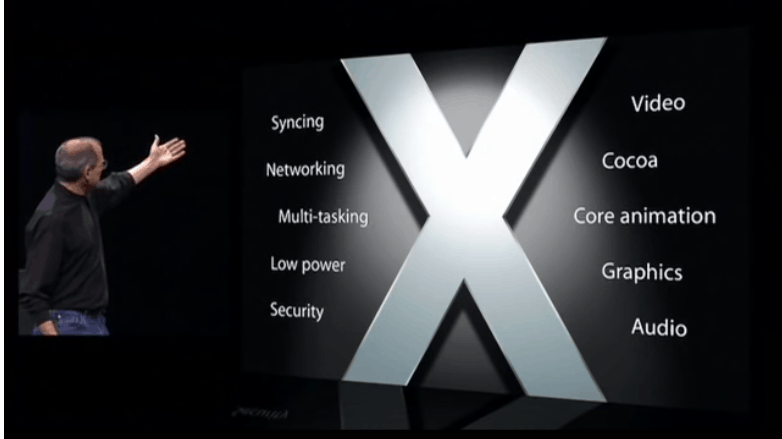

He described software on other mobile phones as “like baby software” and claimed the iPhone ran on Mac OS X. This was an exciting revelation for mobile phone application developers, because other mobile phone platforms were rudimentary and difficult to develop on. For the first time, mobile phone development would approach the experience of developing desktop applications.

Jobs used a little of his powers of reality distortion, claiming “We have invented a new technology called multitouch, which is phenomenal,” without acknowledging any of its previous inventors. Apple’s main genius behind this claim, Wayne Westerman had not even been invited to the event.

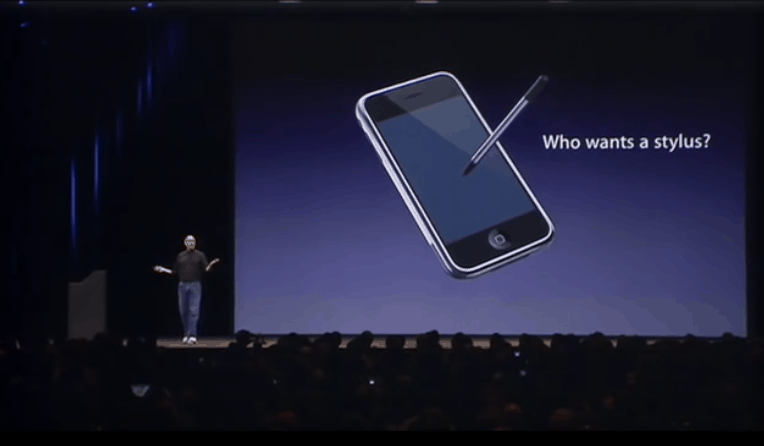

Jobs unveiled the new multi-touch UI by teasing the audience again:

“How are we gonna communicate? We don’t wanna carry a mouse. So what are we gonna do? Oh, a stylus, right? We’re going to use a stylus, right? No! Who wants a stylus? You have to get them and then you put them away and you lose them. Yuck! Nobody wants a stylus!”

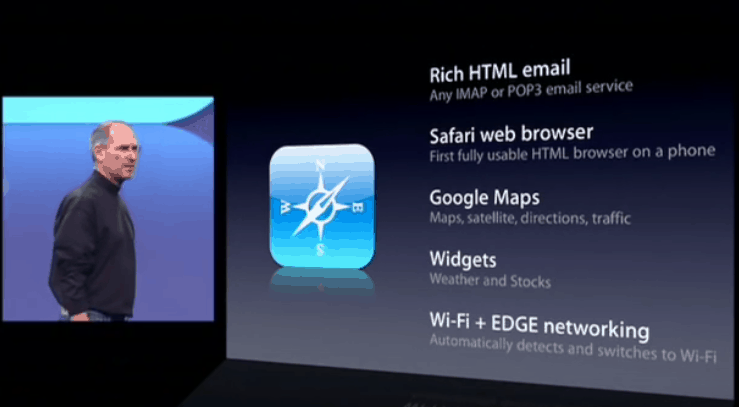

The iPhone came with HTML email, the Safari web browser, the first fully usable HTML browser on a phone, and Google Maps.

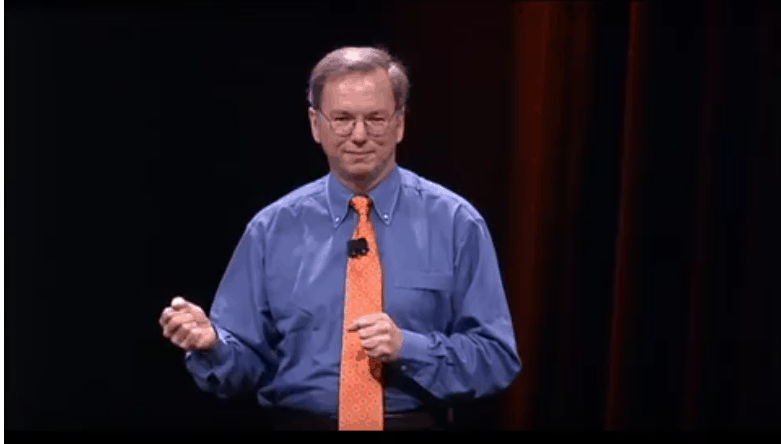

Jobs then welcomed on stage Google CEO Eric Schmidt. To understand why this is significant, we must explain the back story behind Apple and Google in the mid-2000s.

Apple <3 Google

Beginning in 2006, Apple and Google had a blossoming relationship with each other, as they had services that were mutually beneficial.

As an example of this, although Jobs deemed the iPhone prototype to be too sensitive to let most of his own employees know anything about it, he was comfortable showing it off to Google’s Larry Page, who suggested they add Google Maps. Jobs immediately agreed to this, and Google agreed to letting Apple engineers walk out of their office with the full source code to Google Maps, without any written contract signed.

Google Maps was relatively new, as it launched on desktop and laptop devices in February 2005. The implementation of Google Maps on a phone made it easier than ever before to navigate and explore new locations.

Schmidt also suggested that Apple include a YouTube app on the iPhone. Although Jobs did not immediately agree to this, it was an idea that he had under consideration.

Schmidt at Macworld

Jobs then welcomed on stage Google CEO Eric Schmidt, a new member of the Apple board. Schmidt had done business deals with Jobs many years earlier when Schmidt was at Sun Microsystems and Jobs was at NeXT, and they shared a mutual respect for each other. On Aug. 29, 2006, Apple issued a press release explaining the new strategy:

“Eric is obviously doing a terrific job as CEO of Google, and we look forward to his contributions as a member of Apple’s board of directors,” said Steve Jobs, Apple’s CEO. “Like Apple, Google is very focused on innovation and we think Eric’s insights and experience will be very valuable in helping to guide Apple in the years ahead.”

Schmidt gave a brief speech full of flattery for Jobs as he spoke about how their partnership helped each company focus on the areas that they were best at and how the company cultures at Google and Apple were similar.

The rapturous applause for Apple’s collaboration with Google helped to convince Jobs that working with Google on a YouTube app was also a great idea. Schmidt handed the stage back to Jobs, who announced that Google was not the only tech giant they were partnering with.

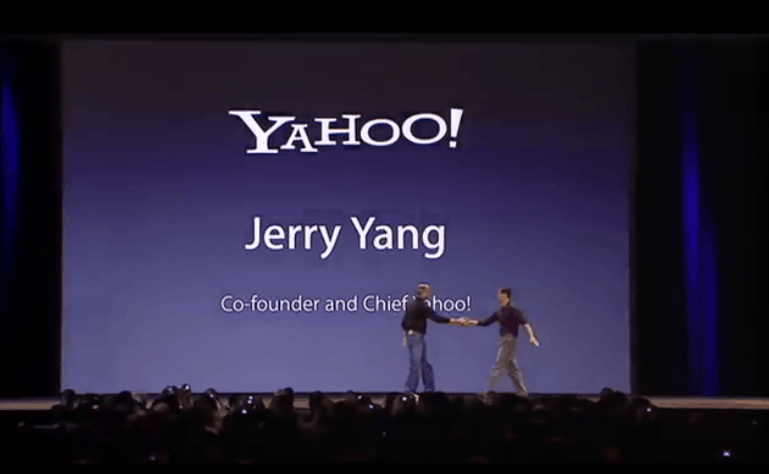

Yahoo Partnership

The iPhone offered users a choice between the Google and Yahoo search engines, and Yahoo IMAP email services. Jobs welcomed Yahoo co-founder and chief Jerry Yang to the stage next. Yang said he was hoping to launch Yahoo’s new technology OneSearch on the iPhone shortly and be successful in providing Web 2.0 services on mobile devices.

Jobs claimed the iPhone had five hours of battery life for video, talk time, or browsing. By launch time, Apple increased this claim to eight hours of calls, seven hours of video, or 24 hours of audio. Apple filed for more than 200 patents based on its various innovations.

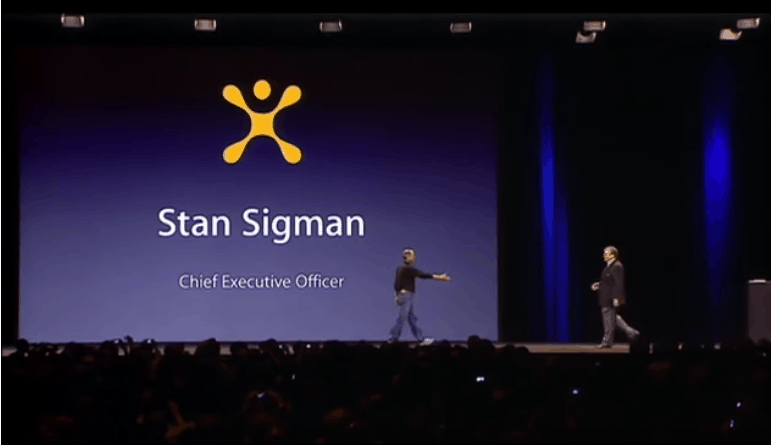

The final guest to take the stage was Cingular CEO Stan Sigman. Cingular partnered with Apple as the sole network provider in the United States, and the iPhone sold in Cingular stores as well as Apple Stores. Sigman announced that Cingular was now part of AT&T and claimed together they were raising the bar.

Jobs concluded by saying the mobile phone market was so huge that a one percent market share meant 10 million units. Apple was aiming for this market share by the end of 2008.

Jobs had a friendship with computer science pioneer Alan Kay going back to the 1980s, when Kay told Newsweek that the Macintosh was the “first computer worth criticizing.”

At the end of Macworld 2007, Jobs handed Kay the iPhone and asked, “What do you think Alan, is it worth criticizing?” Kay replied “Make the screen bigger, and you’ll rule the world.”

Critical Reception and Sales of the First iPhone

The iPhone launched in the United States on June 29, 2007, with a 3.5 inch and 160 pixels per inch display, a 2-megapixel camera, WiFi, Bluetooth, stereo headphones with a microphone switch, proximity sensor, ambient light sensor, and an accelerometer for sensing when to switch between portrait and landscape modes.

It retailed at $499 for the 4GB model or $599 for the 8GB model, with a two-year contract. Jobs justified this as value for money by arguing that you are effectively buying a $199 iPod and a $299 smartphone and getting a lot of extra features for free. However, this was a little misleading, as the fifth generation iPod came with 80GB of storage, whereas the iPhone had only a fraction of that space as well as a shorter battery life.

In the buildup to launch, the hype surrounding the product reached extreme proportions. The biggest Apple fans referred to it as “the Jesus phone.” This slang term began as a spoof article by Gizmodo blogger Brian Lam, but in the run up to the iPhone’s launch, the term was picked up and popularized by the mainstream media. Even Lam’s call for the hyperbolic reference to die did little to dampen enthusiasm for the new phone.

Many reviews of the iPhone were extremely positive. TIME magazine awarded it Invention of the Year 2007, calling it “the phone that changed phones forever.”

At the GQ Awards in London, Edge from U2 presented Jony Ive with the Product Designer of the Year award, announcing “GQ’s Product Designer of the Year is the creator of the iPod, the iPhone, and quite simply everything we know and love about Apple. He brings beautiful objects to the masses, he is the truly gifted Jonathan Ive.”

Microsoft CEO Steve Ballmer was one dissenting voice. He argued that it was too expensive to be successful: “It’s the most expensive phone in the world. And it doesn’t appeal to business customers because it doesn’t have a keyboard, which makes it not a very good email machine.”

Microsoft was working in partnership with Nortel to produce their own smartphone, so it is not surprising that Ballmer wanted to dampen down the iPhone hype, but his view had some merit.

Microsoft was working in partnership with Nortel to produce their own smartphone, so it is not surprising that Ballmer wanted to dampen down the iPhone hype, but his view had some merit.

David Pogue wrote the article for The New York Times, The iPhone Matches Most of Its Hype, where he both praised and criticized it:

“The iPhone is revolutionary; it’s flawed. It’s substance; it’s style. It does things no phone has ever done before; it lacks features found even on the most basic phones.”

Pogue was especially enthusiastic about the web browser, which gave an experience far better than anything else on the market, but noted, “The browser can’t handle Java or Flash, which deprives you of millions of Web videos.”

Several technology journalists noted that the battery life was insufficient and fell short of Apple’s claims. Not everyone was pleased by Apple’s decision to make the battery almost impossible to be replaced. The 2 megapixel camera was reported to be inferior to the technology in Nokia’s high end phones, and it couldn’t be used to record video because Apple hadn’t had enough time to write the necessary software. For their first iPhone, Apple did not treat the camera as a very high priority, but this attitude changed with the later models.

Another frequent complaint was that without WiFi access, web browsing was painfully slow due to use of the aging EDGE cellular network at a time when other phones used 3G. And because the iOS platform was so new, there was a lack of software available for it at the time of launch: It shipped with 16 apps, and there were no more available for download.

Jobs was firmly against the idea of opening up the iOS platform to anyone other than Apple. He told The New York Times, “You don’t want your phone to be like a PC.” And on the day of the launch he argued, “You don’t want your phone to be an open platform. You don’t want it to not work because one of those three apps you loaded that morning screwed it up.” This ultrapurist attitude displeased developers and consumers alike.

Some consumers also wanted the freedom to choose a carrier of their choice, but the iPhone was locked to use only the network provided by AT&T. At the time, several telecommunications companies, including AT&T, took an aggressive stance toward anyone offering unlocking services, and the practice of unlocking mobile phones was the subject of much legal dispute across both Europe and North America.

All of these factors were part of the reason why, although there was much enthusiasm for the iPhone, early sales of the iPhone were much lower than those of more established companies, such as Nokia and Samsung.

iPhone Sales Slow Down

The opening weekend of sales was a huge success. Media organizations around the world reported die-hard Apple fans queueing up outside Apple Stores for many hours for the chance to buy an iPhone. Laura Ingle reported the launch day buildup at the New York City Apple Store, and during an interview with Newsweek’s Steven Levy, a man surprised everyone by grabbing the microphone from her before being wrestled to the ground. Ingle and Levy resumed the interview a minute later, but both were visibly shaken by the incident.

It was also reported that the iPhone was sold-out for the first couple of months it went on sale; however, that was mainly due to a supply shortage.

A lesser known fact was that third quarter sales were sluggish. Apple responded to this disappointment by abandoning the 4GB model and cutting the price of the 8GB model down to $399. With the price cut and the launch in Europe, Apple sold more than a million devices over the Christmas period.

Although sales were gaining momentum by the end of 2007, Apple had a very long way to go if they were going to meet the 1 percent market share they were aiming for.

Developer Backlash Against the iPhone

Meanwhile, as excitement was growing over the possibilities of such a powerful smartphone, an assortment of blog posts from developers sprang up requesting Apple open up the platform to third-party developers.

Within Apple, many engineers also wanted to offer a software development kit for the iPhone, but Jobs argued that third-party applications could place Apple in legal jeopardy: “We don’t want to bear the liability of you not being able to call 911 because some badly written app took the whole thing down.”

In June 2007, Apple’s developer conference, WWDC 2007, began with a fake Steve Jobs poking fun at Windows Vista and Zune and announcing he had no choice but to quit and shut Apple down. Then the real Jobs walked onstage and announced, “You can write great apps for the iPhone: they’re called ‘web sites.’”

John Gruber found this claim to be almost as phony as the fake Jobs and responded that this insulting spin was something that developers could see straight through. Other smartphone manufacturers were allowing third-party developers to write apps for them, while Apple was lagging behind.

Freeing the iPhone

Developers weren’t the only group disgruntled with the limitations of the iPhone and Apple.

A group of hackers called the iPhone Dev Team decided consumers should be free to choose their preferred network carrier with the iPhone. They found the baseband processor chip that locked the phone to the AT&T network, soldered a wire onto it, and disabled it. They wrote a program to enable the iPhone to work with any wireless carrier.

On Aug. 21, 2007, George Hotz posted a YouTube video of the world’s first unlocked iPhone, demonstrating it making a call on the T-mobile network.

As the iPhone could only connect to Macintosh computers, college student David Wang posted instructions for making the iPhone work with Microsoft Windows.

The original iPhone had a number of security vulnerabilities, including a bug that crashed its Safari browser when a user navigated to a webpage with a TIFF image on it. Hackers found this could be used to seize control of the operating system.

This practice became known as jailbreaking, and hackers created a jailbreakme website where a “swipe to unlock” button made an otherwise tedious process very simple. The iPhone Dev Team even had a guy on the inside: Ben Byer, who worked as a senior embedded security engineer at Apple, also went by the alias “bushing” and was one of the core members of the iPhone Dev Team.

Jobs once told the media that dealing with jailbreakers was “a cat and mouse game,” adding, “I’m not sure if we are the cat or the mouse.” Byer played the game as both the cat and the mouse.

Jay Freeman released Cydia for jailbroken iPhones in February 2008. Cydia was a kind of predecessor to the App Store that allowed users to download apps, redesign the screen layout, and make many other customizations that were not officially allowed by Apple.

In 2008, jailbreaking was (ostensibly) against the Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1998 (DMCA). Although Apple never sued any jailbreakers, hackers risked becoming criminals just for opening up the Apple’s platform.

Every three years, the U.S. Copyright Office convenes a “rulemaking” to consider granting exemptions to the DMCA. The Electronic Freedom Frontier (EFF) had been arguing for exemptions to this legislation since it was first introduced. In 2009, it went up against Apple.

The Legal Case For and Against Jailbreaking iPhones

On May 1, 2009, Apple executive Greg Joswiak (vice president iPhone Product Marketing), debated the merits of jailbreaking with the EFF at a court hearing in California.

Joswiak argued, “Jailbreaking hacks and modifies the OS, and by doing such, infringes upon Apple and third-party software. And this destabilizes what is otherwise a vastly beneficial ecosystem. That’s because when you modify and hack the iPhone OS, anything can go wrong.”

After describing the various successes of the iPhone product, Joswiak explained Apple’s aim: “We want to protect the product from modification and copying, protect our software from being modified and copied, because these OS modifications can cause damage.”

Joswiak said even though only 1 percent of iPhones were jailbroken, apps for jailbroken iPhones were “responsible for the overall number-one crashing bug on the iPhone.” He spoke about Apple’s parental controls and argued that jailbroken apps “would risk exposing children to age-inappropriate content.”

He was also concerned that the practice could “risk damaging Apple’s brand” because “for people who have jailbroken phones, they don’t even oftentimes realize that the problems that they have trace back to having jailbroken phones.”

Replying on behalf of the EFF, Friedrich von Lohmann announced that he was a big fan of Apple and the iPhone. He described Apple’s concerns as paternalistic and agreed that “many users will opt not to jailbreak their phones in light of the very concerns that have just been highlighted.”

Lohmann compared the case to buying unofficial parts on a car: “I have a Toyota.

Toyota would, of course, prefer that I use nothing but authentic Toyota parts and Toyota dealers for service, and that they would also prefer that I not modify my Toyota in ways that might be dangerous to me. I appreciate all that, but it is my automobile at the end of the day.”

He disputed Joswiak’s lower estimate on jailbroken phones, stating, “There are at least 1.8 million jailbroken iPhones currently out there, constituting roughly 10 percent of iPhones in release.”

Lohmann explained that some third-party developer apps were barred from the official App Store for Apple’s commercial benefit:

We have now the support of Mozilla and Skype who have talked about why their applications have been excluded. In the case of Mozilla, Apple does not permit alternate browser frameworks on the iPhone. And in the case of Skype, they now have an application in the App Store, but it is not allowed to use the 3G data network in order to place calls. That is also a limitation imposed by Apple.

He concluded by disputing Apple’s argument on security: “Let’s let a thousand flowers bloom. If there’s anything we’ve learned in the last 10 years, security flourishes when there are lots of competitors trying to provide it, rather than one provider that everyone has to count on together.”

A Win for Free Choice

On July 26, 2010, the EFF issued a press release celebrating three exemptions to the DMCA, including the Copyright Office’s decision that jailbreaking in order to use an independently created application that has not been approved by Apple or other smartphone makers fell within fair use.

In 2012, the EFF again asked the U.S. Copyright Office for an exemption to the DMCA legislation, arguing, “These restrictions harm competition, consumer choice, and innovation.” The pursuits of the iPhone Dev Team were the primary example used in their petition. The Copyright Office renewed the exemption for smartphones in their final rulemaking but did not extend it to other devices.

The popularity of jailbreaking and Cydia was one of the many reasons why Apple decided to create their own App Store. In early 2008, iPhone consumers severely lacked choice, but the App Store changed all of that.

Scott Forstall began pushing Jobs hard to allow third-party apps in 2007. He said, “Steve, I’ll put the software together, we’ll make sure to protect it if a crash occurs. We’ll isolate it; we won’t crash the phone.” Jobs announced a change of heart on Apple’s website in October 2007: “Let me just say it: We want native third-party applications on the iPhone.”

“Sometimes when you innovate, you make mistakes. It is best to admit them quickly, and get on with improving your other innovations.” – Steve Jobs

In February 2008, when Apple released a 16GB model of the iPhone, they made it available in either black or white. This gave users the ability to put twice as many songs onto their smartphone. But most consumers decided to wait for the next generation iPhone.

On March 2008, Jobs unveiled the iPhone software roadmap and released the iPhone Software Development Kit (SDK), allowing developers to make their own iPhone applications.

The Release of iPhone 3G

At Apple WWWDC 2008, Jobs announced the iPhone 3G. Although most of the hardware was the same as on the original phone, it offered many stronger selling points over its predecessor.

The iPhone 3G had faster 3G network speeds, enterprise support and third-party application support and was available in many more countries than the original iPhone.

Jobs admitted that the original iPhone was too expensive, revealing that 56 percent of would-be iPhone customers in the United States cited this as the reason they had not yet bought one.

Jobs demonstrated how loading the National Geographic website was 2.8 times faster on the iPhone 3G than on the original iPhone, which was significantly faster than competing Nokia and Treo 3G phones, and only slightly slower than on a WiFi connection.

The iPhone 3G also offered improved battery life, better quality speakers, and an assisted Global Positioning Sensor.

Best of all for the average consumer was that the $399 price tag for the 8GB model was slashed to just $199 for the iPhone 3G.

Apple had failed to launch in Asia by that point, so they decided to launch the iPhone 3G there. The iPhone 3G launched on July 11, 2008, in 22 countries, with launches in a further 48 countries throughout the world over the next few months. Apple finally had a truly mainstream device on sale.

App Store Makes iPhone Sales Skyrocket

The introduction of the App Store for the iPhone and iPhone 3G created a virtuous cycle for Apple: The more apps that became available on the store, the more the iPhone sold. The more iPhones sold, the more developers became interested in the growing market.

The biggest selling app in the first year of the iPhone was the unexpectedly successful joke app, iFart. Free publicity on both late night and daytime talk shows, and some inappropriate sound effects at an Ohio city council meeting, helped to skyrocket the number of downloads. It sold 100,000 copies, at 99 cents each, within just the first two weeks and has since gone on to make its lead developer Joel Comm over half a million dollars.

In an interview with Cult of Mac, he revealed,

I pulled my executive team to the conference room and we went to the whiteboard and started writing down all kinds of ideas. None of us can remember who came up with the idea of a fart machine, but we just cracked up when we thought about it and said, ‘We have to develop this.’ That was it. A bunch of grown men allowing their inner 12-year-old to express themselves. We knew it would sell.

On Oct. 21, 2008, Apple announced its Q4 financial results and revealed it had sold 6.9 million iPhones in that quarter alone, smashing the overall 10 million iPhone sales target that it had set for itself in 2007.

Jobs bragged, “Measured by revenues (not units), Apple has become the world’s third-largest mobile phone supplier.” He also stated that a customer would download the 200 millionth app from the App Store the very next day.

In 2009, Apple’s marketing department captured the essence of what made demand for the iPhone 3G so strong in its 29-second commercial, “There’s an App for That.” This very simply demonstrated that no matter what you wanted to do, there was probably an app available for doing exactly that. The slogan was so catchy that Apple decide to trademark it.

While Apple was thrilled with their spectacular growth, a new competitor had recently entered the field who was set to give them even more strife than market leaders Nokia and Samsung.

Join us in Part 14 for the birth of Android.