Welcome to Part Six of our journey through time, learning how the Internet has evolved and studying the effect it has had on our lives.

In Part Five, we studied the first browser war between Microsoft and Netscape. We learned that shortly after Microsoft overtook Netscape in market share, Netscape CEO Jim Barksdale argued that Microsoft had a monopoly on the operating system market, and that it was guilty of anticompetitive practices.

But was Microsoft actually guilty of this accusation, or was Netscape exaggerating the truth in order to hurt its rival? This question, among others, needed to be weighed by a court case.

The Department of Justice hired David Boies as its main litigator, and so began the U.S. government’s antitrust trial against Microsoft.

Leading the defense was Microsoft’s Bill Neukom.

Federal antitrust case begins

The trial began on October 19, 1998, at the Courthouse for the District of Columbia.

District Court Judge Thomas Penfield Jackson said the focal question of the trial would be whether the company had “maintained its operating-system monopoly through exclusionary and predatory conduct.”

Boies began the trial by accusing Microsoft of coercion as a standard operating procedure.

Boies played selected clips of Gates’ deposition, which portrayed him as highly ignorant of coercive practices that were alleged to have been committed. “I had no sense of what Netscape was doing,” Gates said of Netscape’s business strategy.

Boies contradicted this assertion by showing Gates’ 1995 memo “The Internet Tidal Wave,” which included the telling line:

“A new competitor, born on the Internet, is Netscape. Their browser is dominant, with 70 percent usage share, allowing them to determine which network extensions will catch on.”

After accusing Microsoft of wanting to extend its “choke-hold” to the Internet, Boies showed additional memos from Gates saying:

“I think there is a very powerful deal of some kind we can do with Netscape.”

“We could even pay them money as part of the deal, buying some piece of them or something.”

Boies surmised: “What you have here is, in and of itself, an attempt at monopolization,” and labelled Microsoft’s decision to give away Internet Explorer for free with Windows as “a predatory pricing campaign.”

Boies also presented Marc Andreessen’s extraordinary comment about Netscape’s June 1995 meeting with Microsoft:

“It was like a visit by Don Corleone. I expected to find a bloody computer monitor in my bed the next day.”

Boies argued that even Microsoft’s close allies, such as Intel, were bullied and that Microsoft was telling other companies what products they could or could not ship. He argued that Microsoft would succeed in “murdering” Netscape if the court did not intervene.

Microsoft’s attorney John Warden denied all of these allegations, and defended Gates’ professional image:

“The antitrust laws are not a code of civility in business, and a personal attack on a man whose vision and innovation have been at the core of the vast benefits that people are reaping from the Information Age is no substitute for proof of anticompetitive conduct and anti competitive effects.”

Warden accused the government of relying on email snippets taken out of context and seeking to demonize Bill Gates by chopping up his videotaped deposition in a manner that took Gates’ statements out of context.

First Witness

The first witness was Netscape CEO James Barksdale, who had prepared a 126 page written testimony and arranged for it to be shared with reporters.

In it he described a meeting with Microsoft as “something I had not ever seen happen in my more than thirty years of experience with major U.S. corporations.” He also stated that Microsoft threatened to “crush Netscape, using its operating-system monopoly” if Netscape produced a Windows 95 browser that competed with Internet Explorer.

Barksdale also claimed:

“Netscape has shown an amazing ability to withstand the kinds of anticompetitive pressures Microsoft has put on it, and has been strong enough and innovative enough to reinvent its business model in the face of the slew of Microsoft actions designed to “cut off Netscape's air supply.””

John Warden complained that the testimony contained “fourth-hand hearsay,” which was inadmissible and should be stricken, but Judge Jackson ruled that the hearsay evidence would be heard.

Warden argued that software companies had always combined features to make it easier for consumers and that was all Microsoft was doing. In his cross-examination, Warden asked Barksdale to define the “monopoly product” term used in his testimony.

Barksdale replied that it was “a product that has a clear dominance in the market to the extent that the market no longer has a free choice.”

When asked where he’d first heard the “air supply” quote, Barksdale said it was used by Oracle CEO Larry Ellison to mean “disadvantage a competitor.” He also admitted that he did not remember a specific instance where any Microsoft employee had said those words, but he knew that it had been reported in the press.

As part of the cross-examination, Warden claimed Netscape wanted to sabotage Microsoft. Warden quoted Marc Andreessen saying that he would “reduce Windows to a set of poorly debugged device drivers.” Barksdale said it was merely a joke from Andreessen.

Microsoft’s lawyer submitted as evidence an email sent from James Clark, who founded Netscape, to a Microsoft executive proposing that Microsoft became an investor in Netscape: “Working together could be in your self-interest as well as ours.” This came as a surprise to Barksdale, and Warden cast doubt on the truthfulness of James Clark, with Barksdale conceding “I regard him as a salesman.”

Warden proposed the idea that consumers were better off with free browsers than they would be if they needed to pay for them. Barksdale replied that consumers would be hurt because of the lack of incentives for developers to improve on free browsers.

Boies asked whether Microsoft withheld the software Netscape needed to support Windows 95. Barksdale said, “Microsoft did not provide these APIs until October 1995, which caused us to miss most of the holiday selling season.”

Boies produced evidence that Microsoft’s deal with Apple was predicated on Apple dumping Netscape Navigator as its default browser. Apple’s Fred Anderson wrote: “Apple needed to ensure that Microsoft would continue to provide MS Office for Mac or we were dead. They were threatening to abandon Mac. Trading card was making Internet Explorer default browser.” Microsoft had effectively teamed up with Apple against Netscape, despite many Apple users stating a strong preference for Netscape’s browser.

Second Witness

The America Online (AOL) senior vice president of business affairs, David Colburn, was up next. At this time AOL provided Internet Services for 40 percent of online users, and had a history of battles with Microsoft.

Two years earlier, in 1996, AOL signed an agreement with Netscape to licence its browser, but abandoned it the very next day in favour of an exclusive contract with Microsoft allowing them to be featured on Windows 95.

Warden showed a document as evidence that AOL viewed Internet Explorer 4 to be technically superior to Netscape’s browser, as well as a memo showing that AOL was wary of Netscape as a potential competitor and wanted to instead be an ally. AOL sought to avoid Netscape expanding into their business area.

AOL CEO Steve Case had considered getting a seat on Netscape’s board, but he preferred to seek a way to take control of Netscape’s website. Warden labelled this a “market division proposal.”

Colburn responded that he was merely searching for a strategic relationship, but through his testimony it became clear that Microsoft was not the only company seeking to build partnerships against competitors. In fact, it was a normal part of competitive business strategy.

Boies argued that the difference was that unlike AOL, Microsoft was a monopoly, and the law prohibits a monopoly from doing what a non monopoly can do. Microsoft’s counter-offer to AOL had compelled them into shunning Netscape, Boies said.

Whether Microsoft’s behaviour was illegal, or good business, depended on Judge Jackson’s ruling on whether Microsoft was a monopoly.

Third Witness

Senior vice president of software engineering for Apple, Dr. Avadis Tevanian, was sent by Steve Jobs to testify, since it would be significantly less damaging for Apple’s delicate relationship with Microsoft than if Jobs himself had testified. Tevanian prepared a written testimony arguing that:

“Microsoft has aggressively employed this anticompetitive strategy against Apple in an effort to control not only the market for Internet browsers, but the emerging market for technologies that create, send, receive and display multimedia content.”

Before speaking to the witness, Boies played more of Gates’ deposition, showing Gates answering questions on Microsoft’s business relationship with Apple. During the deposition, Gates said he did not recall seeing a Wall Street Journal about Microsoft telling Apple to “stay out of the multimedia software market.”

Tevanian testified that “Microsoft has written steps into its operating system to ensure that a Quicktime file will not operate reliably on Windows” and had pressured computer manufacturers not to include QuickTime on their machines.

Microsoft denied these allegations, saying the two companies cooperated to “ensure that our respective tools and applications interoperate for the benefit of consumers” and quoted Steve Jobs stating Internet Explorer was “the best browser out there.”

Judge Jackson later revealed his thoughts to Ken Auletta on Tevanian’s examination: “The sense I got was that Apple was genuinely apprehensive that Microsoft was going to pull the plug on them, and I believed them.”

Fourth Witness

Steven McGeady from Intel took the stand.

Intel was ostensibly Microsoft’s foremost ally, having worked with them since 1984. By 1998, around 80 percent of all PCs had an Intel processor and a Windows operating system, which were often described by the colloquial shorthand “Wintel”.

McGeady believed that Microsoft was an “evil corporation” and disagreed with the official Intel position regarding Microsoft.

Boies began his examination by playing another embarrassing video clip of Gates’ deposition, where Gates claimed he had no knowledge of any effort to convince Intel not to do business with Sun, or to persuade them against going into the software business.

McGeady contradicted Gates’ point, describing a meeting where Microsoft threatened to withdraw support for Intel microprocessors. Boies produced an email from Gates saying “we are the software company here and we will not have any kind of equal relationship with Intel on software.”

McGeady testified that Microsoft had threatened to withhold crucial technical support from Intel if the chipmaker did not stop developing software that would compete with Microsoft's products.

He also alleged that a senior vice president at Microsoft told him he intended to “extinguish” rival Netscape and “cut off Netscape's air supply” by giving away Internet Explorer for free.

Microsoft argued that McGeady was a disgruntled executive who had missed out on promotions, and whose memory of the events were in contrast with that of other Intel executives.

As an unlikely, but fierce enemy of Microsoft, McGeady played the role of a maverick and was one of the most memorable witnesses for the Department of Justice.

Fifth Witness

Glenn E. Weadock, computer consultant and president of Independent Software, Incorporated, was summoned to challenge the assertion that integrated browsers better serve the interests of customers.

He argued that nobody outside of Microsoft ever described a web browser as operating system software.

Microsoft argued the distinction between application and operating system was becoming more muddled, and that once optional software was now seen as essential.

Sixth Witness

John Soyring of IBM was summoned by the government in the hope that he would demonstrate that Microsoft even bullied giant companies.

Soyring blamed Microsoft’s applications barrier for the relative failure of IBM’s OS/2 operating system, saying,

“Many important applications designed to run on Windows have not been made available in versions designed to run on OS/2.”

He also said Microsoft’s restrictive contracts limited software companies’ ability to sell products to Windows competitors.

Soyring criticized Microsoft’s Java strategy, accusing them of conniving to use its version of Java to block software developers from writing universal applications.

Boies produced an email by Bill Gates on his fear of Java, stating:

“The Java religion coming out of the software group [at IBM] is a big problem …. They continue to use their PCs to distribute things against us.”

Microsoft defended themselves, arguing IBM had allied with Sun and Netscape, and produced an email from IBM to Netscape saying:

“We must work together using all of our collective contacts to establish Java as the standard. We must move quickly to pre-empt Microsoft.”

Microsoft argued the failure of OS/2 was because it was harder to use than Windows, and that it required more memory than many consumers could afford to buy.

Seventh Witness

Economist Frederick R. Warren-Boulton was summoned next, but his statements on Microsoft’s monopoly were overshadowed both by how Boies was using Gates’ deposition and by some breaking news.

The deposition was becoming increasingly embarrassing to Microsoft’s legal team, and John Warden complained that it was played in “bits and pieces.” He asked for it all just to be played at once.

Judge Jackson replied, “I think your problem is with your witness, not with the way in which his testimony is being presented.” He added, “Mr Gates has not been particularly responsive to his deposition interrogation.”

Breaking News

Also overshadowing Warren-Boulton’s testimony on November 24, 1998, was the big surprise news that Netscape had agreed to sell to AOL for $4.2 billion of its stock. Netscape’s stock price rose quickly as the news was absorbed.

The deal was due to close in the spring of 1999, pending shareholder and regulatory approval.

AOL also announced it was partnering with Sun Microsystems. Under a new three-year agreement, AOL and Sun would develop and market products to help Internet users access America Online brands, with the aim of building an Internet-service company to rival Microsoft and IBM.

This was bittersweet news for Microsoft: they were about to face a new industry threat, but it was good news for their antitrust case.

Microsoft’s Bill Neukom said the new alliance showed that market competition was alive and well, and that if AOL replaced the Internet Explorer browser with Netscape Navigator, Netscape could become the most frequently used browser again.

“It proves indisputably that no company can control the supply of technology. We are part of an industry that is remarkably dynamic and ever changing.”

AOL’s Steve Case initially said AOL would continue to bundle Internet Explorer with the AOL online-service software, because “we want to continue to have AOL bundled with Windows.”

On the courthouse steps, David Boies told reporters, “If AOL plans to continue to use the Microsoft browser after the acquisition because that's the only way they can get access to the [Windows] desktop, that's a pretty strong indication of the barriers to competition that Microsoft has created.”

Eighth Witness

Dr. James Gosling, the creator of the Java programming language, was next to take the stand. His testimony explained how Java offered software developers cross-platform development opportunities, which were a threat to Microsoft’s business model.

Once again, David Boies was delighted to play another episode of Gates’ deposition, where Gates denied he was concerned about Java.

This statement contradicted Gates’ own email saying “[Java] scares the hell out of me,” and also that of a Microsoft email sent to Gates saying, “If we looked further at Java being our major threat, then Netscape is the major distribution vehicle.”

Microsoft’s attorney countered by reading an email from Gosling advocating a deceptive relation with Microsoft, giving them “the illusion of working with them” while working to “beat them.”

Ninth Witness

David J. Farber, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania, gave a technical explanation of software and discussed “the negative consequences of permitting Microsoft to add what are now applications to create an ever-larger, monolithic software package.”

Microsoft had claimed that integrating Internet Explorer into Windows 98 resulted in efficiencies.

Farber stated that this claim was misleading because the same effect could be achieved without bundling of the browser software.

“This is because there are no technical barriers that prevent Microsoft from developing and selling its Windows operating system as a stand alone product separate from its browser software.”

Tenth Witness

Edward W. Felten, a Princeton University computer scientist, agreed with Farber, demonstrating that Internet Explorer could easily be removed from both Windows 95 and Windows 98 without endangering any of the non-Web browsing functions of the Windows system.

He argued that the decision to combine the browser with Windows offered consumers no technological benefits over separately installed products.

Microsoft’s attorney argued that Felten had merely hidden the browser, not removed it. Felten had failed to uninstall the browser, because it was an integral part of the operating system.

Eleventh Witness

William H. Harris, president and CEO of Intuit, which produces tax preparation software, said Windows had become a “choke point” that software application vendors and providers of Internet related content and services were required to utilize in order to gain access to customers.

He argued that Microsoft had used its monopoly power to push software companies into shutting out Netscape.

Boies played another episode of Gates’ deposition revealing yet more of his memory lapses. Gates could not recall asking Intuit to forgo any promotional agreements with Netscape, despite receiving an email from Microsoft’s senior vice president, Brad Chase, informing him that Intuit had agreed to “not enter into marketing/promo agreements with Other Browser manufacturers.”

John Warden highlighted that Netscape had failed to produce a browser with Intuit’s requested features, whereas Internet Explorer had succeeded. Under cross-examination, Harris admitted that in some respects Intuit and other companies had behaved like Microsoft, such as by offering money to computer manufacturers to load their software onto new PCs.

Final Witness for the Government

Dr. Franklin M. Fisher, an economics professor at MIT, was called to answer the one of the trials most vital questions: Is Microsoft a monopoly?

Fisher quoted the depositions of PC makers who felt obligated to buy the Windows operating system, and said Microsoft’s claim that they were seriously challenged by other operating systems was a joke.

However, Fisher damaged the government’s position when he was asked if consumers were being victimized by Microsoft by answering, “On balance, I would think the answer is no, up to this point.”

Fisher believed that the real harm to consumers would come in the future, with rising prices and stifled innovation. But this belief was attacked as mere speculation.

In a direct question to Fisher, Judge Jackson quoted a Washington Post interview with AOL CEO Steve Case: “AOL’s merger with Netscape has no bearing on the Microsoft case, as nothing we’re doing is competitive with Windows. We have no flight of fancy that we can dent in any way, shape, or form what is a monopoly in the operating system business.”

Fisher agreed entirely with this argument and argued that Microsoft had taken anti-competitive actions to protect the dominance of its Windows operating system.

The Microsoft Witnesses

Microsoft’s witness list was mostly Microsoft executives, but also included an economist, Richard L. Schmalensee, and John Rose of Compaq Computer.

Microsoft Vice President Brad Chase was able to demonstrate that Internet Explorer was, in some respects, technically superior to Netscape’s browser, and highlighted a strategic agreement between AOL and Sun showing they planned to reinvigorate Netscape.

However, the Microsoft executives generally failed to significantly alter the momentum of the case. The government had failed to find any PC maker willing to testify for them as a witness, but the cross-examination of Compaq’s John Rose allowed David Boies to attack Microsoft on its relationship with Compaq.

Rose was forced to admit that PC makers had no viable alternative to Windows. David Boies then showed that Compaq wanted to “feature the brand leader, Netscape” in May 1996, but after Microsoft threatened to stop shipping Windows to them, Compaq surrendered and made Internet Explorer the default browser on all their PCs.

After the final testimony, Judge Jackson called a recess and declared he would be issuing his Findings of Fact in due course.

Microsoft Press Campaign

Bill Gates invited Ken Auletta of the New Yorker to his office and complained that both Microsoft and Linux had been treated unfairly by the press:

“Only in a courtroom can somebody say ‘Hey, Linux is a serious competitor’ and the press laughs in a way that the judge thinks, ‘OK, that must be a false statement, that must be posturing.’ Here, in my world, there is intense competition from Linux and many other products.”

Gates admitted he regretted that Microsoft hadn’t reached an out of court settlement in 1998, adding, “We’ve always wanted to settle this thing.”

In another press event, Steve Ballmer told analysts, “There is more competition today and stronger competition today than I think I’ve ever felt in my nineteen years at Microsoft.”

Microsoft also ran adverts in The Washington Post and The New York Times to get their own points across to consumers, saying:

“Consumers did not ask for these antitrust actions – rival business firms did. Consumers of high technology have enjoyed falling prices, expanding outputs, and a breathtaking array of new products and innovations.”

In the Washington Post and New York Times advertisements, Microsoft argued that unbundling Internet Explorer from Windows would penalize consumers because they want computers to be simpler to use, not harder.

It also argued that their gain in market share was due to Internet Explorer’s technical superiority over Netscape Navigator.

Findings of Fact

Judge Jackson released the court’s decision on November 5, 1999.

The court sided with the Department of Justice on almost every point.

It decided that Microsoft was a monopoly whose market share would likely “climb even higher over the next few years” and that competitors did not have a fair chance of succeeding against them.

It defined an “applications barrier to entry” for Microsoft competitors. Also referred to as a chicken and egg problem, it explained that most consumers only use an operating system for which there already exists a large set of high quality applications.

Judge Jackson ruled this fact “would prevent an aspiring entrant into the relevant market“ and found little adoption of Linux in lieu of Windows.

Regarding Java and Netscape’s browser, Jackson found they had the potential to diminish the applications barrier and that Microsoft was alarmed by their popularity and the threat they posed to Microsoft’s business.

The court also found Microsoft had withheld crucial technical information from Netscape.

But the fiercest condemnation of all was saved for the final paragraph, where it found Microsoft had deterred competitive investments, hurt competitors, and stifled innovation.

Judge Jackson later referred to the legal maxim falsus in uno, falsus in omnibus, as a part of his decision process: after noting contradictions in the Microsoft testimony and the documentary evidence, the whole credibility of their case was cast into doubt.

After hearing the news, Bill Gates read out a written statement saying “we respectfully disagree.” Microsoft lodged an appeal and were hopeful that the Court of Appeals would reverse the ruling.

Mediation

On November 19, 1999, Judge Jackson appointed Richard Posner, Chief Judge of the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals, to serve as a mediator, with the hope that both sides could be persuaded to settle. Microsoft was pleased with this decision as the legal team respected the jurist as an authority on antitrust law, a successful author, and an economist strongly in favor of the free market.

Posner invited both sides to lunch at the Standard Club in Chicago, where he invited presentations but urged everyone to keep their talks in strict confidence.

Over the next few months, Posner was successful in nurturing a good relationship with Bill Gates and impressing on him the need to settle.

However, the mediation was complicated by the additional demands of 19 state attorneys general. According to a Microsoft executive, Posner said negotiations with them was “like herding cats; they’re hopeless.”

On April 1, 2000, Posner released a statement beginning:

“After more than four months, it is apparent that the disagreements among the parties concerning the likely course, outcome, and consequences of continued litigation, as well as the implications and ramifications of alternative terms of settlement, are too deep-seated to be bridged.”

Posner thanked the Department of Justice, Microsoft, and Judge Jackson. He did not thank the states! Bill Gates said, “Ultimately, it became impossible to settle because the Department of Justice and the states were not working together.”

Conclusions of Law

On April 3, 2000, Judge Jackson’s declared his conclusions of law, confirming that Microsoft had broken antitrust law.

“Microsoft maintained its monopoly power by anticompetitive means and attempted to monopolize the Web browser market, both in violation of [section] 2 of the Sherman Act.”

Jackson declared Microsoft had unlawfully tied its Web browser to its operating system and mounted “a deliberate assault upon entrepreneurial efforts.”

On that day, Microsoft’s market value fell by an enormous $80 billion as investors sold Microsoft stock en-masse.

The following day, Jackson announced he wanted to use the Expediting Act to bypass the appeals court and go directly to the Supreme Court.

Microsoft’s chiefs remained unrepentant. Steve Ballmer told The Washington Post: “I feel deeply that we behaved in every instance with super integrity.” Bill Gates appeared on PBS’s Nightly Business Report declaring, “Microsoft is very clear that it has done absolutely nothing wrong.”

Remedy Hearing and Ruling

Court proceedings resumed on May 24, and Judge Jackson referred “an excellent brief” from the Computer and Communications Industry Association and the Software and Information Industry Association, which recommended Microsoft’s browser business be split into a separate company.

This brief quoted Steve Ballmer as saying “40 percent of the functionality of the desktop version of Windows 2000 is useless without a Windows 2000 server.” Judge Jackson asked Microsoft’s lawyers if this quote was correct, and after a five minute recess to find out, the lawyers replied they could neither confirm nor deny the quote, and that it was in any case irrelevant to the trial.

Jackson ruled that Microsoft had 90 days to establish a compliance committee with at least three board members outside of Microsoft.

Microsoft filed a motion for a stay with the Court of Appeals, accusing Judge Jackson of “an array of serious substantive procedural errors that infected virtually every aspect of the proceedings.” The Court of Appeals agreed to hear the case.

Judge Jackson responded by agreeing to postpone any conduct remedies until the appeal process had completed, but also asked the Supreme Court to directly review his decision.

Final Ruling

The final ruling was issued on November 12, 2002. It was a conduct based remedy, prohibiting Microsoft from anticompetitive practices with its OEM licensees, and requiring it to disclose more of its APIs and related documentation to independent developers for the purposes of interoperating with the Windows operating system.

To ensure compliance, Microsoft also agreed to appoint a panel of three people who had access to Microsoft's systems, records, and source code for five years.

It was a very long and costly legal battle for Microsoft, however the agreement protected Microsoft’s most prized objective: being allowed the freedom to continue to tie other software with Windows in the future.

Nine states and the District of Columbia believed the settlement didn’t go far enough, but on June 30, 2004, the U.S. Appeals Court rejected those objections and approved the settlement.

Microsoft Wins the Browser War

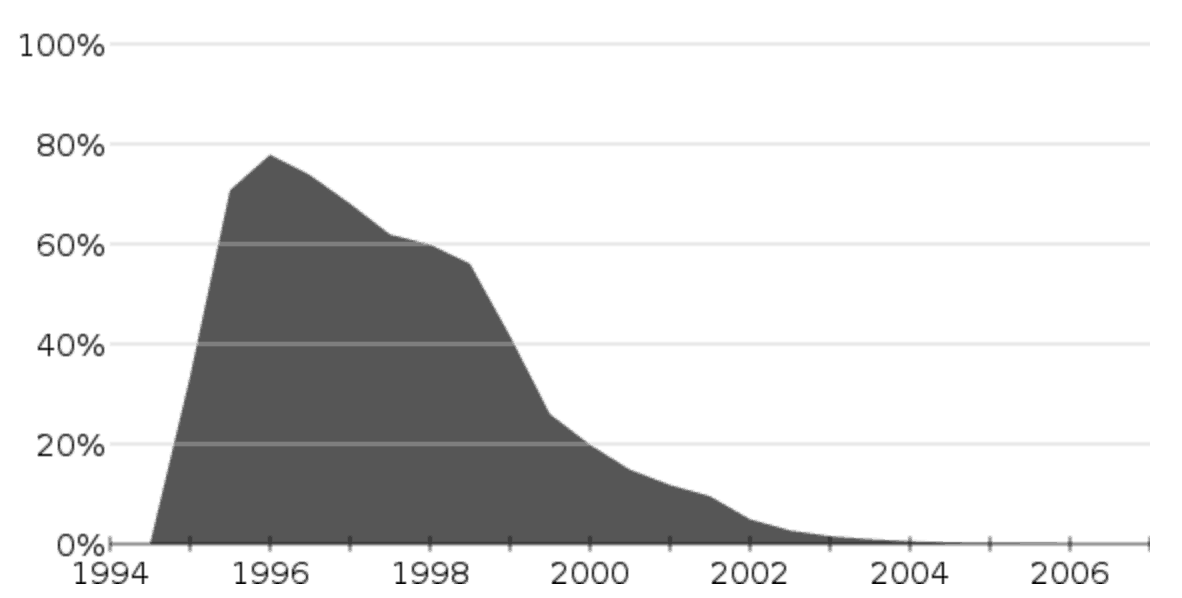

During the year 2000, Microsoft’s share of the browser market surged to 86 percent and Netscape’s fell below 14 percent.

The Netscape browser continued to improve under AOL’s ownership, but not at a rate fast enough to compete with Microsoft or halt its market decline. The rush to add more features to the product made it more difficult for the development team to address quality issues. Users complained of slow performance, bugs, and even crashes.

AOL CEO Steve Case continued to insist the Netscape browser was superior to Internet Explorer, but due to the contract it signed with Microsoft before the Netscape takeover, it continued to promote Internet Explorer, rather than its own browser, through the AOL website.

Several years later, AOL decided to cease its browser development as of Netscape Navigator 9. Microsoft had won.

In “Business @ The Speed of Thought”, the follow up to Bill Gates’ bestselling book The Road Ahead, he wrote a chapter titled “Bad News Must Travel Fast,” describing the web browser technology as a threat that could have easily put Microsoft out of business forever. He credits “J. Allard, Steven Sinofsky (my technical assistant then), and a few other people“ for the sharp move to embrace the web.

But above all, he credits Microsoft’s willingness to hear bad news and act on it, citing the attack on Pearl Harbour as a lesson in the need to always be psychologically prepared for bad news.

Throughout the browser war, both companies shared opposite views of each other, but also exactly the same mentality regarding themselves. They both viewed themselves as the underdog trying to buck the odds against aggressive outsiders. Netscape’s Andreessen said:

“We were a little startup. They were Microsoft, coming to town.”

But Amazon’s founder Jeff Bezos was supportive of Gates, saying “my opinion is he is unfairly vilified by a high percentage of people that I run into in high-tech circles.”

Bill Gates concluded the chapter with the following quote:

“I’ve seen us as an underdog every day for the last twenty years. If we don’t maintain that perspective, some competitor will eat our lunch…One day an eager upstart will put Microsoft out of business. I just hope it’s fifty years from now, not two or five.”

In this article, we’ve looked at a bitter rivalry over the final years of the 20th century.

I hope that this has given you a strong flavor of both sides of this controversial story. If you want to dig deeper, you can read the testimonies in full on the Department of Justice site.

Over these same years, there was another equally important industry battle going on between other key Internet technology companies.

Join us in Part Seven to discover the story of the birth of Yahoo and Google.