With more than 2 billion users, Android is the most widely used smartphone operating system in the world. But that kind of success once looked like a long shot. Here, we’ll take a look at the improbable rise of Google’s smartphone from beneath Apple’s shadow to the top of the market.

The story began in Palo Alto at the end of the 20th century, when Andy Rubin, Joe Britt, and Matt Hershenson founded Danger, a company specializing in mobile phone technology. Andy Rubin was an enormous fan of robots and named his company after the catchphrase of the robot from Lost in Space.

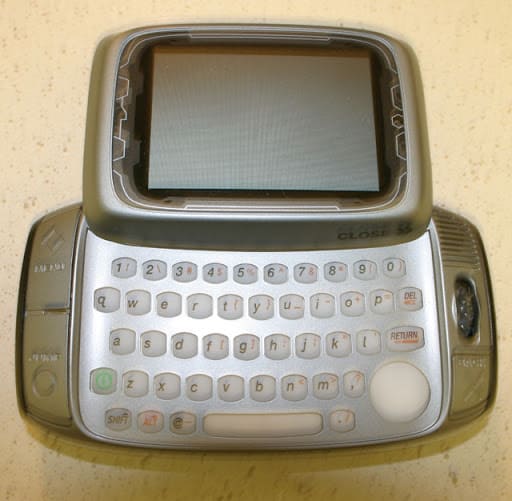

They launched the Danger Hiptop smartphone (also known as the T-Mobile Sidekick) in 2002. Its DangerOS operating system was largely based on Sun Microsystems’ Java. The phone’s screen was only monochromatic, but the device offered downloadable games as well as web browsing.

In 2003, Danger’s board decided to replace Rubin as chief executive, and shortly after Rubin decided to start a new company. The experience at Danger gave Andy Rubin the business relationships, confidence, and inspiration to found Android Inc. with Rich Miner, Nick Sears, and Chris White.

Android Inc.

Once Android Inc. was established, all employees quietly worked in secrecy, revealing only that they made software for mobile phones. They were a small team, so to develop more quickly, they adopted the best open source software that they could find, including the Java platform.

By 2005, Rubin was interested in partnering with a major company in an effort to dominate the smartphone industry. He later told a story of his experience pitching to Samsung in Seoul:

“I pitch the whole Android vision to them like they are a venture capitalist. And at the end and I am out of breath, with the whole thing laid out … there is silence. Literally silence, like there are crickets in the room. Then I hear whispering in a nonnative language, and one of the lieutenants, having whispered with the CEO, says, ‘Are you dreaming?’ The whole vision that I presented, their response was ‘You and what army are going to go and create this? You have six people. Are you high?’ is basically what they said.”

Rubin’s disappointment did not last long, because two weeks later Android Inc. was acquired by Google for an undisclosed sum believed to be at least $50 million.

Although the acquisition went mostly unnoticed in the press, Ben Elgin wrote a piece for Business Week and asked Google for comment. A spokesman replied only “We acquired Android because of the talented engineers and great technology. We’re thrilled to have them here.” Except for Samsung, all of Google’s business rivals, along with the general public, were left in the dark about what Android was really about.

What was Android really about? Rubin’s original vision was a low-level software platform that phone vendors could build on top of. Schmidt agreed that it was to be software only, but considered building up the software into a full-featured operating system. Page, on the other hand, wanted Google to build its own phone. So even within Google, it took time, many meetings, and many iterations before for the aims of the project were fully understood.

Android Inc. became a wholly owned subsidiary, but key employees were kept during the acquisition. Rubin led a new team developing a mobile device platform powered by the Linux kernel. Google spent tens of millions of dollars purchasing licences for much of the open source software that Android used, but it could not agree on terms with Sun Microsystems, which felt Google was modifying their Java platform too much.

The “Sooner” Prototype

Working in a first-floor corner of Google’s Building 44, surrounded by Google ad reps, Rubin’s team quickly grew to about four dozen engineers. In partnership with HTC, they worked together on the “Sooner” prototype, which was a lot like the highly popular BlackBerry phones. It had a hardware keyboard and small screen.

In Part 13 we learned that Google was an important partner for Apple and helped to make the iPhone a major success.

The Google team that was helping Apple with the iPhone did not reveal the iPhone secrets to the Android team, which worked in a different building. To the Android team, Jobs’ announcement of the iPhone at Macworld came as a shock.

The Android team realized they needed to dramatically change direction. Google engineer Chris DeSalvo reflected on the effect the iPhone announcement had on Android. “What we had suddenly looked just so … nineties. It’s just one of those things that are obvious when you see it.”

Andy Rubin watched the iPhone announcement in sheer disbelief. Picturing the unsightly HTC prototype, he said “Holy crap, I guess we’re not going to ship that phone.”

Beyond the shock of how good the iPhone looked, the Android team was also shocked to see their own CEO onstage flattering their competitor’s product. “Steve, my congratulations to you. This product is going to be hot.”

Both of these shocks combined to create a morale problem within the team. Could they really go up against Apple’s iPhone and win? But they were also spurred on by something Jobs said during the announcement: that Apple had the “first fully usable” internet browser on a phone. For ex-Danger employees, this was an insult to the memory of the Danger Hiptop. Rubin stated Apple was “the second adopter of the web standard.”

Schmidt, Brin, and Page told Rubin they were still committed to the Android project and pushed him to hire more staff and increase its rate of progress. Brin and Page both owned iPhones and criticized the Android team whenever they saw features that didn’t match up to the iPhone experience. Page demanded that all Android screens load in less than 200 milliseconds and the user interface be easy to navigate with one hand.

Although there are many advantages to being first to market with a new type of product, there are occasions when it is more beneficial to release later. For Google, knowing more about its competition gave them a strategic advantage. Apple had granted AT&T exclusive rights in the United States for four years. This meant all other network carriers were shut out from Apple’s business plans, so Google would have to find a new company to work with.

However, as iPhone went from hype to genuine success story, pressure mounted on the Android team. Part of this pressure came from politics that was forming within Google. Google hired Microsoft’s general manager of Platform Evangelism, Vic Gundotra and tasked him with getting Google software onto mobile phones.

Gundotra had been a fan of Apple products since he first used the Apple II when he was 11 years old and was proud to admit “Even when I worked for 15 years for Bill Gates at Microsoft, I had a huge admiration for Steve and what Apple had produced.”

Gundotra believed that Apple’s iPhone was so good that it was destined to become the number-one selling phone. Believing sales of other phones were largely doomed, he put a stop to Google supporting many BlackBerry and Windows Media phones. Some employees were furious and quit the company in protest. Although the Android project was not yet under any direct threat, Gundotra’s support of the iPhone caused tensions to build.

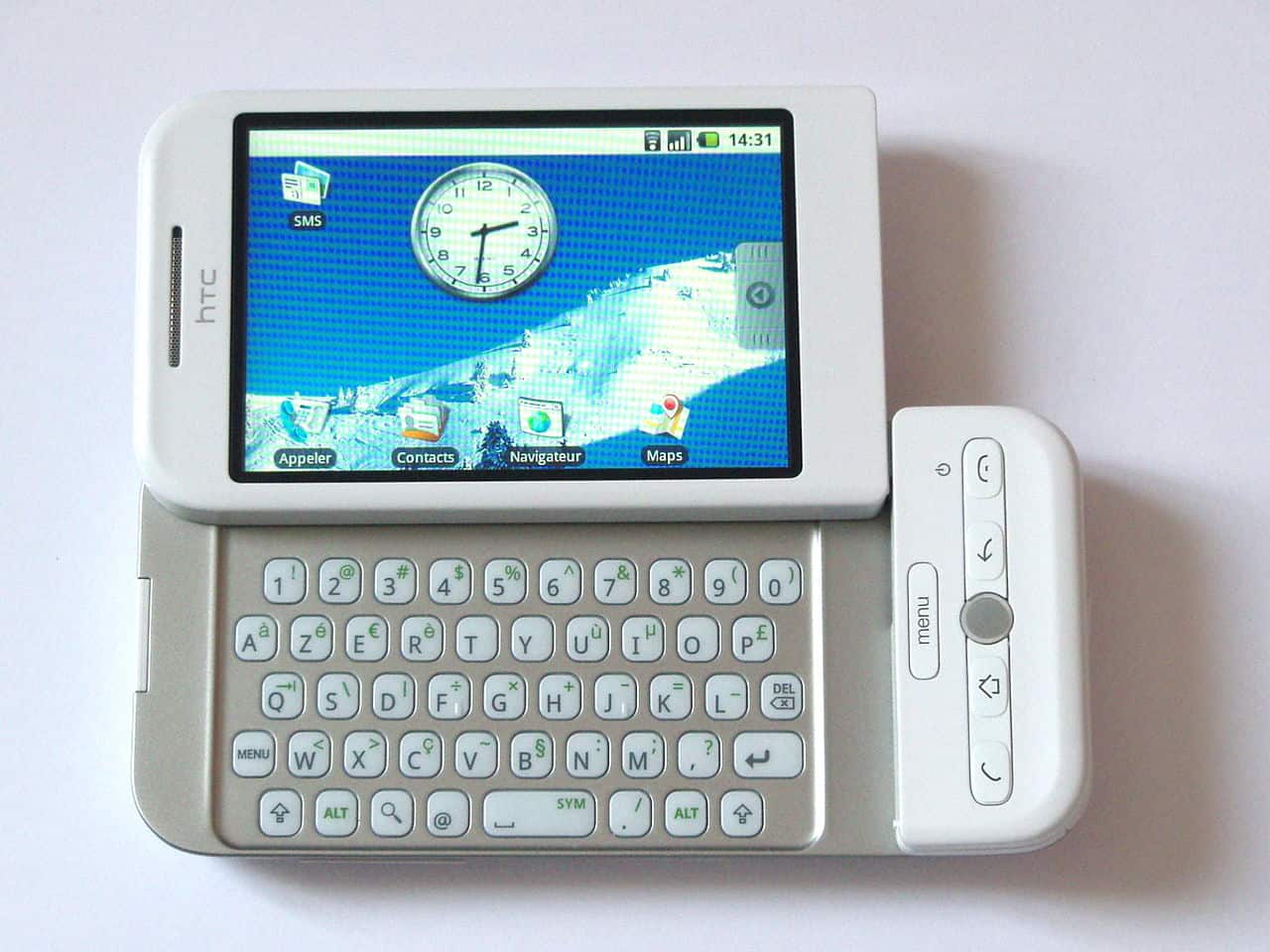

Photo by Jolie O’Dell, CC BY 2.0

Gundotra was enjoying great relations with Jobs and suspected the Android project could ruin that. He asked the Android team, “Convince me that this [Android] is something we [Google] should believe in.” The whole of Google’s mobile business strategy became contentious.

In 2007, the press began talking about Google producing a device to compete with the iPhone, which they dubbed the “gPhone.” Google executives deflected and evaded media requests for months, until they were ready to speak.

The first major news article was by John Markoff for The New York Times, “I Robot: The Man Behind the Google Phone,” and the headline caused some confusion. Google had not made a phone itself and was relying on its partners to build phones for them.

Although Markoff had few known details about Android to share, he was remarkably prescient in foreseeing that “Google, though not in a dominant position in this field, might be able to replay the strategy that Microsoft itself used to bulldoze Netscape in the mid-1990s. Just as Microsoft successfully ‘cut off’ Netscape’s air supply by giving away its Explorer web browser as part of the Windows operating system, Google may shove Windows Mobile aside if the Google Phone is given away to handset makers.”

Open Handset Alliance

On Nov. 5, 2007, the Open Handset Alliance was announced. Android engineers explained that there was no single “gPhone,” but they were developing software that enabled many different mobile phone manufacturers to produce better phones. This consortium included device manufacturers such as HTC, Motorola, and Samsung; wireless carriers like Sprint and T-Mobile; and chipset makers such as Qualcomm and Texas Instruments. Together they were called the Open Handset Alliance.

The announcement did not create anywhere near the level of excitement that the iPhone had created.

Major mobile phone companies such as Nokia, RIM, and Microsoft turned down cash offers to be part of the consortium and poured scorn on the idea. Nokia dismissed the announcement, saying “we don’t see this as a threat,” and a member of Microsoft's Windows Mobile team stated “I don’t understand the impact that they are going to have.”

Android Demo

The following week, Brin and engineering director Steve Horowitz introduced and demonstrated Android to the world on YouTube, including a demonstration with a large touch-screen.

The rudimentary user interface mostly added weight to Jobs’ claim that the iPhone was years ahead of anything else, but Android’s use of OpenGL ES hardware acceleration meant games such as Quake could run smoothly on a mobile phone. Brin finished the announcement by offering $10 million to reward the developers that build the best new Android applications.

Later that day, an Apple employee who asked to remain unnamed claimed to have received a furious phone call from Jobs: “Did you see the video? Everything is a f****** rip-off of what we are doing.”

The “Coopertition” of Google and Apple

Schmidt began a business relationship with Jobs way back in 1993 when Jobs pitched the benefits of Objective-C to Sun Microsystems, where Schmidt worked.

By the time Google’s CEO Schmidt was appointed to Apple’s board in 2006, Schmidt and Jobs were old friends. At the time, he told Jobs that there was an early stage mobile phone project going on within Google, and they agreed to monitor the situation.

Jobs was also friends with Brin and Page. Back in the year 2000 when Google investors were asking Brin and Page to hire a new CEO, they said they wanted to hire Jobs. Although there was never any chance of Jobs leaving Apple for Google, their compliments endeared Jobs to Brin and Page.

Apple and Google made a secret illegal agreement that restricted them from hiring employees from each other, effective from March 6, 2005. Although the deal expanded over the next year to include many other technology companies such as Adobe, Dell, Microsoft, Ebay, and IBM, email evidence suggests the close relationship between Apple and Google, initially, gave rise to these dubious business practices.

By 2007, Google and Apple were financed and run in such a way that it wasn’t clear to what degree they were partners or competitors.

In addition to Schmidt, Arthur Levinson was also board member of both companies, and two other Apple board seats belonged to Bill Campbell and Al Gore, who were both advisers to Google.

Schmidt likened the Google-Apple partnership to international diplomacy: “Countries can have a long list of grievances with each other, but it is in their mutual best interests to figure out a way to work together. The alternative—a lack of a relationship, or war—is destructive for everyone. For example, China and the United States have lots of issues, but there is so much trade between the two countries that we must find ways to maintain and build our relationship in spite of our differences.”

Although Jobs was initially enraged by the Android demo that he saw, Schmidt, Brin, and Page reassured Jobs that Google was not making its own phone and that Android would not be a direct competitor to the iPhone. Schmidt told Jobs that supporting the iPhone was a higher priority for Google than the Android project was. One Apple executive said Jobs “basically said to me, ‘I believe in my relationship with these guys [Brin and Page] that they’re telling me the truth about what’s going on.’”

Then in spring 2008, talks on renegotiating the Google search and Google Maps agreements turned sour. Gundotra visited Apple’s campus and got into a shouting match with Schiller over how much Google should be paying Apple and how much data location data it should be receiving. In addition to latitude and longitude, Google wanted to know connection type and cell tower information. Schiller refused, saying it would be a violation of the users’ privacy. This disagreement helped to convince Gundotra that Android would be the future of Google.

In an attempt to avoid a court battle with Apple, Google made their head of engineering, Alan Eustace, available to answer any questions Jobs had about Android. But by the summer of 2008, Jobs concluded that Google was trying to string him along.

Jobs traveled with Forstall to Google’s headquarters to see if he could persuade them to stop the Android project. He threatened to sue if they copied any iPhone features and offered them one or two icons on the iPhone home screen “if we had good relations.”

Google argued that although Apple was the first company to invent a successful multitouch smartphone, they hadn’t invented multitouch or most of the other technologies that are part of the iPhone.

Fearing an expensive and brand-damaging lawsuit, Schmidt, Brin, and Page backed down and agreed to remove features such as pinch to zoom from the first Android phone. Many Google employees were unhappy with this capitulation, not least Rubin who thought about quitting the company and put up a sign in his office that read “STEVE JOBS STOLE MY LUNCH MONEY.”

But although Google had lost the first battle, this was just the beginning of a war.

The Public Relations War

The Eucalyptus e-book reader app, offering users access to thousands of classic books in the public domain, was rejected from Apple’s App Store in May 2009 on the grounds that users of the app could potentially download the Kama Sutra, which it deemed “contains inappropriate sexual content.” Apple subsequently backtracked and approved the app, but this did not stop The Guardian from labelling Apple as “Big Brother.”

This dent to Apple’s image was greatly exacerbated on July 28, 2009, when Google announced that Apple had rejected their app from the App Store.

Google acquired telephone services company GrandCentral in 2007. It was like Skype and offered calls over the internet. Google used this technology to create a Google Voice app for Android and iPhone. The app offered features that weren’t yet available on the iPhone and essentially took the core communication features of the iPhone away from Apple and onto Google’s cloud.

On July 31, 2009, the Federal Communications Commission wrote to Apple asking why Apple had refused to allow the Google Voice application on its App Store. Among the questions asked was “Did Apple act alone, or in consultation with AT&T, in deciding to reject the Google Voice application and related applications?”

Apple replied “Contrary to published reports, Apple has not rejected the Google Voice application, and continues to study it. The application has not been approved because, as submitted for review, it appears to alter the iPhone’s distinctive user experience by replacing the iPhone’s core mobile telephone functionality and Apple user interface with its own user interface for telephone calls, text messaging and voicemail.”

After Apple approved Google Voice on its App Store, Google had scored a double win against them: It created a controversy that harmed Apple’s brand and gave free publicity to their app, and then it was granted permission to put its app on the iPhone and start enticing consumers away from Apple’s features onto their own.

Despite the negative press coverage, Apple continued to enjoy strong and improving iPhone sales. Google and their partners knew that to have any hope of catching up, they would need to produce phones that were as desirable as the product leader. The first attempt fell short of achieving this ultimate goal but was popular enough to be declared a successful start.

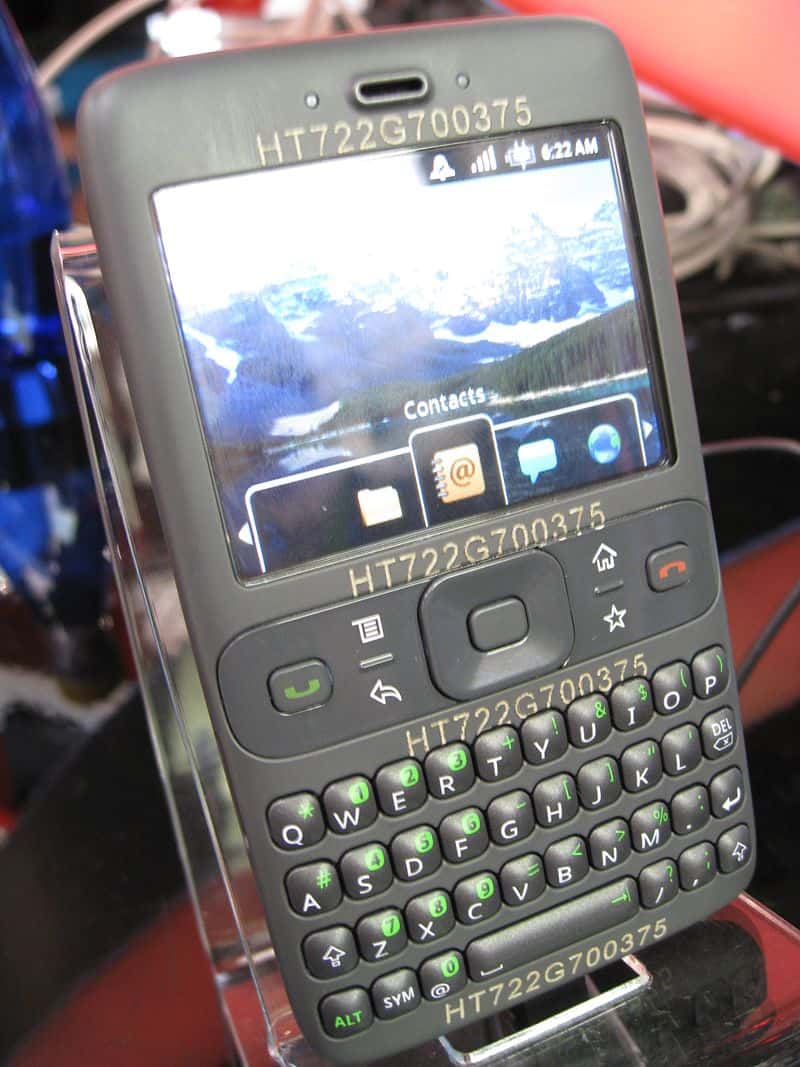

HTC Dream

The first Android phone was the HTC Dream (also known as the T-Mobile G1 in the USA and parts of Europe, and as the Era G1 in Poland). It had mixed reviews, and the original Android operating system was generally thought to be inferior to iOS due to the lack of features such as multitouch gestures and virtual keyboard, but it showed promise for the future.

The Android 1.1 update was released on Feb. 9, 2009, with bug fixes as well as minor features such as the ability to save attachments in messages.

The first major improvement to Android was the 1.5 release, commonly known as “Cupcake.” This included a range of new features and enhancements such as support for third-party virtual keyboards, support for widgets, video recording and playback, copy and paste features in web browser, auto-rotation option, and the ability to upload videos to YouTube or photos to Picasa.

To see how Android has evolved from the Cupcake release, see this video by YouTubers “it assistors.”

In April 2009 T-Mobile announced that it had sold over a million G1s in the United States, accounting for two-thirds of the devices on its 3G network.

It was not an iPhone killer, but it was successful enough to pave the way for more sophisticated models.

Android Chasing the iPhone

In this article we’ve covered the early days of Android. It launched under the shadow of Apple iPhone’s spectacular success, but Android offered distinct advantages that gave it the opportunity to become a big future success.

There is so much more of Android’s story left to tell. In the next episode of our series, we will see how the battle for smartphone supremacy intensified, both in the product innovations and in the courtrooms.