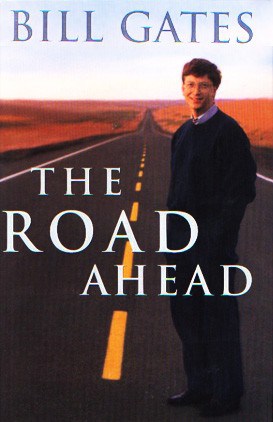

Welcome to Part Four of our journey through time, learning how the Internet has evolved and remembering the effect it has had on our lives.\n\nWe concluded Part Three in late 1995, with NetScape dominating the new industry.\n\nBut Microsoft was busy at work as well, and in November 1995, Bill Gates released The Road Ahead, a book describing a future profoundly changed by the emerging global information superhighway, or, as we more commonly call it today, the Internet!\n\n \n\nArmed with a million-dollar publicity budget, he undertook a five-day tour of Los Angeles, San Francisco, New York, Washington, London, and Paris.\n\nThe Road Ahead occupied the top spot on The New York Times‘ bestseller list for over seven weeks, selling 2.5 million copies.\n\nBill Gates worked throughout the year with distinguished coauthors Nathan Myhrvold and Peter Rinearson on this book. For brevity, we will refer only to Bill, but do not doubt that the contributions of Nathan and Peter also helped make this book the classic it is today.\n\nIn this part of the series, we’ll review this work in terms of the major changes that were predicted, and examine which of these have come true.\n\nOn the inside sleeve, Bill asked the big questions:\n\n

\n\nArmed with a million-dollar publicity budget, he undertook a five-day tour of Los Angeles, San Francisco, New York, Washington, London, and Paris.\n\nThe Road Ahead occupied the top spot on The New York Times‘ bestseller list for over seven weeks, selling 2.5 million copies.\n\nBill Gates worked throughout the year with distinguished coauthors Nathan Myhrvold and Peter Rinearson on this book. For brevity, we will refer only to Bill, but do not doubt that the contributions of Nathan and Peter also helped make this book the classic it is today.\n\nIn this part of the series, we’ll review this work in terms of the major changes that were predicted, and examine which of these have come true.\n\nOn the inside sleeve, Bill asked the big questions:\n\n

- \n

- What is the information highway?

- How will the new technology change our lives?

- Do I have to learn to use a computer?

- Will my job become obsolete?

\n

\n

\n

\n

\n\nIn the foreword he wrote:\n\n“This is meant to be a serious book, although ten years from now it may not appear that way. What I’ve said that turned out to be right will be considered obvious and what was wrong will be humorous.”\n\n

A Revolution Begins

\n\nThe book starts with a brief autobiography of the early part of Gates’ life and career.\n\nBill Gates founded Microsoft with his school friend Paul Allen after realizing Intel’s microprocessor technology would go on to create a hugely profitable industry for the software running on the new chip. The company vision arose from the question: “What if computing were nearly free?”\n\nHis mission to put “a computer on every desk and in every home” was a bold one at the time, and as he wrote this book, he imagined another revolution was about to begin.\n\nHe predicted that all manner of human activity would take place online, and that we would have broader choices in deciding who our friends were and how we spent our time with them.\n\nHe argued that education, and what it means to be “educated,” would be transformed, and he anticipated our sense of identity—who we are and where we belong—opening up.\n\nBill foresaw new technology that would inspire us to new creative heights.\n\nHe imagined stolen devices directing us to their location, and he envisioned the ability to ask any question and get an answer straight away.\n\n

The Beginning of the Information Age

\n\n \n\nIn 1995, technology was beginning to change the ways in which we handle information.\n\nBill echoed Gordon Moore’s consistently borne out prediction from 1965 that computing capacity would double approximately every 18 months. This prediction is known as Moore’s Law.\n\nOne of the errors made in The Road Ahead was the prediction that Moore’s Law would hold for another 20 years, and that by the year 2015 computing would be more than 10,000 times faster.\n\nThis did not occur; although, beginning in 1965, it held true for about 17 years. To increase computing capacity, it is necessary to fit more transistors onto the microchip. In recent years it has become much harder to manufacture smaller transistors efficiently. The equipment needed to produce them is prohibitively expensive, which is why there are only a few surviving chipmakers today.\n\n

\n\nIn 1995, technology was beginning to change the ways in which we handle information.\n\nBill echoed Gordon Moore’s consistently borne out prediction from 1965 that computing capacity would double approximately every 18 months. This prediction is known as Moore’s Law.\n\nOne of the errors made in The Road Ahead was the prediction that Moore’s Law would hold for another 20 years, and that by the year 2015 computing would be more than 10,000 times faster.\n\nThis did not occur; although, beginning in 1965, it held true for about 17 years. To increase computing capacity, it is necessary to fit more transistors onto the microchip. In recent years it has become much harder to manufacture smaller transistors efficiently. The equipment needed to produce them is prohibitively expensive, which is why there are only a few surviving chipmakers today.\n\n

Lessons from the Computer Industry

\n\nBill Gates learned some valuable lessons from mistakes that both Microsoft and its competitors had made.\n\nBill believed a company achieving good write-ups was likely to attract many other good things, such as bigger investments in the company and top talent wanting to come work for them. Conversely, whenever a negative atmosphere takes hold, it becomes harder to keep hold of the most talented employees, and the press are likely to keep writing negative stories.\n\nBill noted a few stories of competitor failures, most notably IBM who were massively successful in the 1970s but had underestimated the business value of the operating system market in the 1980s. The partnership with Microsoft that had IBM licensing MS-DOS was a decision that ultimately benefitted Microsoft more than IBM.\n\nAt the time, MS-DOS was a powerful yet very affordable operating system which helped to sell more IBM PCs. But IBM agreed to a low-cost licensing deal that left Microsoft free to use them like a springboard for selling their operating system to other computer companies.\n\nThey also hedged their bets by offering two high-priced operating system alternatives, and lacked the focus that smaller companies had, meaning it was harder to innovate as quickly.\n\nBill said IBM did not expect their PC would cannibalize their business systems, making the mistake of holding back on PC innovations in order to protect their higher-end products.\n\nXerox also took criticism from Bill, who faulted them for failing to take commercial advantage of their groundbreaking research in graphical user interfaces.\n\nMicrosoft was not shy about borrowing ideas from Xerox (or to some extent Apple Computers) and made a fortune from Microsoft Windows.\n\nThe key lesson Bill wanted us to learn here was to avoid complacency. Bill warned that it’s difficult to recognize a crisis when your business is healthy, but new opportunities and threats appear all of the time.\n\nHe showed an acute awareness that, although Microsoft was and still is a large company, their size doesn’t give any guarantees of success in the Internet business.\n\n

Applications and Appliances

\n\nBill imagined the Internet would end the era of needing to watch your favorite TV show at a specific time and day each week. The 1980s gave us the videocassette recorder, which provided some flexibility, and Bill envisaged a world where the Internet largely surpassed this technology.\n\nHe predicted televisions would be connected to the Internet. He suspected that they would not look like a computer and not have a keyboard, but would have electronics inside or on top of the television somewhat like those of a PC.\n\nVHS would be replaced by discs similar to CDs, and he said those would then be replaced by online video on demand. He also speculated, “HDTV might still catch on.”\n\nBill predicted that almost every home in the United States would have a computer connected to the Internet. He also anticipated pocket-size computers with color screens and significant changes in attitudes to the technology. No one would say “Wow! You’ve got a computer!” anymore.\n\nHe called these pocket-sized computers “wallet PCs,” and said they would have cameras, a phone, an address book, map, compass, calculator, photos, and more.\n\nWhen using the GPS in your “wallet PC,” Bill believed it would allow you to track your location and provide navigation services. He also correctly predicted digital money, the ability to easily pay for goods using it, use of biometric technology for better security, and the ability to have directions read out to you as you drive your car.\n\nThe prediction yet to come true with Bill’s “wallet PCs” is their use to authenticate a person at airport gates. Printed passports are still the norm for us today, and significant security challenges must be surmounted before any computing device can be considered a safer option.\n\nMore advanced still is the ability to have conversations with your computer. Although Bill was optimistic in predicting computers that would be able to decipher arbitrary sentences by 2005, his vision is certainly accurate over the longer term.\n\nA further optimistic prediction was that computers would have the ability to answer complex queries, for example:\n\n”Which major city has the greatest percentage of the people who watch rock videos and regularly read about international trade?”\n\nEven in 2017, computers struggle with this degree of complexity. Wolfram Alpha cannot understand this question at all. Google provides results that are not very related to the question, and while Bing gives an answer, it provides no information to substantiate whether it is the correct one.\n\nHowever, simpler queries such as “What’s the weather today?” have been effectively answered for many years.\n\n

Paths to the Highway

\n\nBill explained the huge investments necessary to build the information highway: $120 billion in the U.S. alone. He expected fiber cable would be run into every neighborhood with new servers and switches adding to the cost.\n\nHe noted that the 28.8k modems of 1995 did not offer the bandwidth needed for full audio and video, but newer technology such as ISDN would change that.\n\nHe repeated the key message he gave to his staff in May 1995: the Internet is the most important single development in the world of computing since the introduction of the IBM PC in 1981.\n\nBill recounted the story of Internet black hat Robert Morris, Jr. and the havoc he caused with the first Internet worm in 1988, but asserted that the Internet was a reliable communication channel for millions of people.\n\nBill himself was fascinated by the art of code breaking as a child. He discusses Internet security, one-way functions, and the naivety of Rivest, Shamir, and Adelman in thinking that a 129-digit number would never be broken.\n\nThe time required to crack a number increases exponentially as the number of digits increases. In the year 1993, a group of academics and hobbyists took on the challenge of cracking the number known as RSA 129 and succeeded a year later.\n\nBill warned “no one should get too cocksure about the security of encryption,” but went on to point out that “Mathematicians today believe a 250-digit long product of two primes would take millions of years to factor with any foreseeable amount of computing power.”\n\n

The Content Revolution

\n\nThe main prediction in the sixth chapter of The Road Ahead is the replacement of printed content with digital content. Bill acknowledged that magazines and other printed documents had distinct advantages over their digital equivalents, but imagined those advantages to be lessened once people have specialized, lightweight electronic book readers.\n\nBill said novels wouldn’t benefit from electronic organization because they are designed to be read from start to finish linearly. This is unlike factual books, which tend to have indexes in the back of the book and can be read in multiple non-linear ways.\n\nHe also predicted personalized newspapers and online encyclopedias, but the most inspiring forecast he made was that newer technology would offer new and exciting opportunities for creative expression, both for artists and for scientists.\n\n

Implications for Business

\n\n \n\nBill anticipated that the Internet would offer new means of collaboration and opportunities to free people from their usual fixed office desks, with the result that businesses would become more efficient and often smaller.\n\nIn 1995, the costs for coordinating information were huge for large businesses, but Bill predicted these problems would be greatly simplified by Internet technology.\n\nBill described the use of emoticons in electronic mail, but said they “probably won’t survive the transition of e-mail into a medium that permits audio and video.”\n\nHe discusses his own business at Microsoft, revealing that he spent several hours a day reading and answering e-mail. He described some of the problems he’d had with people knowing his e-mail address: requests for money, chain mail, and threats of salacious stories about topless waitresses.\n\n

\n\nBill anticipated that the Internet would offer new means of collaboration and opportunities to free people from their usual fixed office desks, with the result that businesses would become more efficient and often smaller.\n\nIn 1995, the costs for coordinating information were huge for large businesses, but Bill predicted these problems would be greatly simplified by Internet technology.\n\nBill described the use of emoticons in electronic mail, but said they “probably won’t survive the transition of e-mail into a medium that permits audio and video.”\n\nHe discusses his own business at Microsoft, revealing that he spent several hours a day reading and answering e-mail. He described some of the problems he’d had with people knowing his e-mail address: requests for money, chain mail, and threats of salacious stories about topless waitresses.\n\n

Education: The Best Investment

\n\nBill painted a future much brighter than what we typically see in the year 2017. However, the technology that is potentially available for use in 2017 is not so different from what he described in 1995.\n\nStrangely, Bill described the World Wide Web as a precursor to the information highway. From the viewpoint of 2017, the World Wide Web almost appears to be the highway itself.\n\nThe World Wide Web of 1995 was so much more basic than it is today that it may have felt more like a stop-gap technology than a long-lasting technology. The terms “information highway” and “information superhighway” were used to mean everything associated with high speed Internet access.\n\nIn recent years, the term “information highway” has fallen completely out of use, while the World Wide Web has not only survived but thrived.\n\n

Plugged in at Home

\n\nBill made the case that ubiquitous Internet access wouldn’t lead us to social isolation.\n\nThis remains a matter of opinion, and certainly there are many examples of us becoming both less and more social as a result of the Internet. Almost everything described about the rise of online social networking has come true, as well as the popularity of multiplayer online games.\n\nThe predictions on how technology might influence architecture are only just beginning to come true. We have seen some early versions of products that will likely become a standard part of future “smart homes.” Already, the amount of space we need for physical things such as books, fax machines, and file drawers has diminished.\n\n

Race for the Gold

\n\n \n\nMost relevant to the year 1995 is the chapter, “Race for the Gold,” wherein Bill discussed the new gold rush atmosphere that the World Wide Web had created.\n\nBill revealed that Microsoft was investing more than $100 million per year on research and development, but later adds, “No one wants to admit to uncertainty” and likened the huge investments made to the story of the blind men and the elephant!\n\nAs we will see in a later episode of this series, his predictions about many companies losing their shirts would prove correct.\n\nIn the year 1995 there were significantly different attitudes to the Internet expressed by governments around the world. Bill credited the UK, France, Germany, and Singapore for their ongoing technological advances and Internet adoption. In the case of China, we hear of “management measures” to control the inflows of data.\n\nBill wrote that it was hard to predict what would happen in Japan due to its relative lack of PCs in businesses, schools, and homes. He was correct to foresee that the Japanese phone company NTT would “play a leadership role” and to suggest that the educational advantages of the Internet would continue to fuel growth in South Korea.\n\nThere was also some commentary on the different viewpoints regarding how much of the processing would be performed on the client versus the server. Bill’s opinion here was that the work would be evenly divided.\n\nBill was especially accurate when he noted that “[t]he battle among software architectures will play out over a long period and may involve potential competitors who have not yet declared their interest.”\n\n

\n\nMost relevant to the year 1995 is the chapter, “Race for the Gold,” wherein Bill discussed the new gold rush atmosphere that the World Wide Web had created.\n\nBill revealed that Microsoft was investing more than $100 million per year on research and development, but later adds, “No one wants to admit to uncertainty” and likened the huge investments made to the story of the blind men and the elephant!\n\nAs we will see in a later episode of this series, his predictions about many companies losing their shirts would prove correct.\n\nIn the year 1995 there were significantly different attitudes to the Internet expressed by governments around the world. Bill credited the UK, France, Germany, and Singapore for their ongoing technological advances and Internet adoption. In the case of China, we hear of “management measures” to control the inflows of data.\n\nBill wrote that it was hard to predict what would happen in Japan due to its relative lack of PCs in businesses, schools, and homes. He was correct to foresee that the Japanese phone company NTT would “play a leadership role” and to suggest that the educational advantages of the Internet would continue to fuel growth in South Korea.\n\nThere was also some commentary on the different viewpoints regarding how much of the processing would be performed on the client versus the server. Bill’s opinion here was that the work would be evenly divided.\n\nBill was especially accurate when he noted that “[t]he battle among software architectures will play out over a long period and may involve potential competitors who have not yet declared their interest.”\n\n

Critical Issues

\n\nThe final chapter, “Critical Issues,” discusses the changes that the Internet might bring to society after 1995.\n\n“The availability of virtually free communications and computing will alter the relationships of nations, and of socioeconomic groups within nations. The power and versatility of digital technology will raise new concerns about individual privacy, commercial confidentiality, and national security.”\n\nBill warned against making hasty decisions, recommending we take our time to consider all the pros and cons before coming to a consensus.\n\nThe biggest concern for the average person in 1995 was neither privacy nor national security. It was the impact the Internet could have on their job security. Bill warned that entire professions and industries would fall into decline, but there would be new industries and jobs created at the same time.\n\nExamples from the industrial revolution and the PC revolution were given, and the argument was made that every job rendered unnecessary would free up workers to achieve bigger and better things.\n\nFrom the perspective of the year 2017, we can see that the development of the Internet and the World Wide Web has indeed created many more jobs and opportunities than it has taken away. The global e-commerce market is now an estimated $22 trillion, and this figure will almost certainly continue to rise.\n\nThe fear that computers would become so “smart” that humans are no longer needed is also discussed. Bill considered it very unlikely to happen within his lifetime.\n\nAlthough computers have replaced human workers in some areas, they do not possess intelligence in the same way that humans do.\n\nThe prospect of being outsmarted by computers remains a concern for some today, and books such as Jerry Kaplan’s Humans Need Not Apply and Ray Kurzweil’s The Singularity Is Near discuss this prospect in more detail.\n\nBill also mentioned the gender imbalance in computing: “Girls are far more active with computers today than twenty years ago, but there are still many fewer women in technical careers. By making sure that girls as well as boys become comfortable with computers at an early age we can ensure that they play their rightful role in all the work that benefits from computer expertise.”\n\nBill recognized that the Internet would make nations more alike and reduce the importance of national boundaries.\n\nHe talked about the risks of losing access to the Internet in a major way, comparing it to the New York City blackouts in 1965 and 1977. Bill argued that computer security had a very good record and that the main reason for breaches was human sloppiness.\n\n

Privacy

\n\nLoss of privacy is another threat that is discussed, with Bill predicting governments would set new policies on privacy and access to information. He said he found “the prospect of documented lives a little chilling,” but suggested it could be a useful alibi if you were to be falsely accused of a crime. Richard Nixon was used for the corollary example.\n\nBill said the levels of privacy in the future would depend on which fear was greater: the fear of surveillance or the fear of crime?\n\nHe noted that, in the year 1995, most citizens wished to protect their privacy but, in the book’s most sombre note, he speculated, “It might take only a few more incidents like the bombing in Oklahoma City within the borders of the United States for attitudes toward strong privacy protection to shift. What today seems like digital Big Brother might one day become the norm if the alternative is being left to the mercy of terrorists and criminals.”\n\nBill discussed encryption algorithms, the concerns of the NSA, and legislation preventing the export of software with good encryption. The effect of the Internet on politics was also mentioned, and Bill suggested electronic voting would have a lower risk of fraud.\n\nHe argued against a “direct democracy” with all issues being put to a vote, saying voters might not understand all the trade-offs necessary for long-term success.\n\nOne of the reasons Bill was optimistic about the future of the world with Internet technology is a touching letter he received from a customer:\n\n“Mr. Gates, I am a poet who has Dyslexia, which basically means I can not spell worth a damn, and I would never have any hope of getting my poetry or my novels published if not for this computer Spellcheck. I may fail as a writer, but thanks to you I will succeed or fail because of my talent, or lack of talent, and not because of my disability.”\n\n

For the Most Part, Bill Got It Right

\n\nWhile not every prediction made in the book has come true, the majority of them have. Overall, it is the most insightful read on the Internet that I have been able to find from the 1990s.\n\nThis article covers just a tiny fraction of the subjects covered in this book. I have found it addresses many issues that are still relevant and important for us today.\n\nAlthough the book is no longer in print, it can be picked up secondhand very cheaply.\n\nIn the next episode, we will return to the battle between NetScape and Microsoft that would become known as the First Browser War.