In Part 21, we covered the early years of WikiLeaks and its founder Julian Assange. At the beginning of 2010, Assange received an enormous collection of information from Pfc. Manning. This included Afghan war logs and Iraq war logs which were controversially published that same year.

Assange became an even more controversial character after he was charged with sex crimes including rape, which he denied. At the end of September 2010, he flew to England where he began work on the biggest campaign yet.

Cablegate is the media term given for the publication and subsequent drama of stories based on 251,287 U.S. State Department communications written by 280 embassies and consulates in 180 countries.

Cablegate Publication (Dis)agreement

For the upcoming release, an agreement was made to grant time-limited exclusive access to The Guardian, Der Spiegel, and The New York Times (NYT).

But the NYT’s derogatory October 2010 piece “WikiLeaks Founder on the Run, Trailed by Notoriety,” infuriated Assange. He had once admired the NYT for its publication of the Pentagon papers, and the military documents that he had provided them with enabled the NYT to write many important stories, including one on the same front page on the same day.

Feeling betrayed, he labelled it an error-ridden sleazy hit piece, and now wanted the NYT to be frozen out of the deal. He began talks with The Washington Post about giving them the scoop instead of the NYT, but did not reach an agreement with them.

The publication of the state cables risked further legal problems not just for WikiLeaks but also for their source Pfc. Manning, so Assange didn’t want to publish until at least November 2010.

Another complication was that there appeared to be a leak within WikiLeaks! Former WikiLeaks programmer Smári McCarthy was one of “about a dozen” WikiLeaks volunteers to abandon ship, according to the NYT, and McCarthy left with a copy of the cables. According to Assange, McCarthy also gave a copy to British-American journalist and WikiLeaks defender Heather Brooke.

Assange had also given an encrypted copy of the cables to Daniel Ellsberg, originally with a view to creating a publicity stunt where he gives the copy to the NYT, thereby associating Cablegate with the Pentagon Papers.

Nobody could be certain that there hadn’t been even more copies shared around. WikiLeaks and the three newspapers realized that if they could not agree to a deal soon, they risked seeing the news break elsewhere, in a manner completely out of their control.

The Guardian agreed to host Assange in their offices to discuss the arrangements on Nov 1, 2000. The reporters were unhappy that he appeared with his lawyers, and scrambled to arrange for their own lawyer to get there as soon as possible.

Heated discussions were tempered with the arrival of two bottles of chablis, but ran on late into the night. On a phone call between the editors of The Guardian and the NYT, it was agreed that the NYT would consider publishing Assange’s response to their article, and would not publish “sleazy hit pieces.

Assange asked for the news pieces to be structured so that they would not come across as anti-American: “There are security exposés and abuses by other countries, these bad Arab countries, or Russia … that will set the initial flavour of this material. We shouldn’t go exposing, for example, Israel during the initial phase, the initial couple of weeks. Let the overall framework be set first. The exposure of these other bad countries will set the tone of American opinion.”

Although this belief was well intentioned, it demonstrated a naivety about the newspaper industry: most readers are not very interested in scandals in Russia or the Middle East, or even consider it news that some corruption exists there. What readers are most interested in is uncovering corruption in their own countries.

Assange also wanted to bring in Spanish and French newspapers El Pais and Le Monde, so that the stories would have a more global impact. The Guardian staff were startled by this request, but agreed to go along with it.

The majority of the cables were unclassified. 101,748 cables (40 percent) were classified as confidential, 16,652 (6 percent) as secret. None were top secret. This was still an enormous quantity of classified information.

The various papers collaborated with each other using Skype, but devised a system of communication that avoided mentioning any classified details. They held pieces of paper with numbers written on them up to their web cameras. These were the reference numbers to the cables.

The U.S. Government officials contacted the papers shortly before the release, citing security concerns and asking for information on what would be published. Part of the work that the journalists had done was to redact information that could endanger anyone as best as they could foresee.

The NYT editor, Bill Keller said “White House officials, while challenging some of the conclusions we drew from the material, thanked us for handling the documents with care.”

Assange was more skeptical of the government’s claims, and wrote to the U.S. embassy in London inviting the ambassador to “privately nominate” examples where publication of a cable could put an individual “at significant risk of harm.”

After the State Department’s legal advisor wrote back claiming the release “would place at risk the lives of countless individuals,” Assange wrote back “I understand that the United States government would prefer not to have the information that will be published in the public domain and is not in favour of openness. That said, either there is a risk or there is not. You have chosen to respond in a manner which leads me to conclude that the risks are entirely fanciful and that you are instead concerned only to suppress evidence of human rights abuses and other criminal behaviour.”

On Nov 10, 2010, Assange was named one of the 25 candidates for TIME person of the year 2010, although his write up was much less enthusiastic than those of other candidates such as Steve Jobs and closer in tone to that of Mark Zuckerberg.

One week before the launch of the cables stories, an international arrest warrant for Assange was issued on suspicion of rape, sexual molestation and unlawful coercion.

On the day before launch, the State Department wrote to PayPal, which WikiLeaks used for accepting donations. The State Department told PayPal that WikiLeaks was considered illegal in the US.

The Moscow Connection?

Assange had an existing business relationship with Swedish filmmaker Johannes Wahlström. Assange was visited by Wahlström’s father, Russian-born Swedish writer Israel Shamir, and was persuaded to give a copy of the cables relating to Russia. According to The Guardian, Shamir introduced himself as “Adam,” one of his pseudonyms, and WikiLeaks spokesman Kristinn Hrafnsson, confirmed that Shamir was their representative in Russia.

Shamir then travelled to Moscow, and according to Kommersant, offered to sell articles based on the cables for $10,000. Shamir also wrote some bizarre articles for Counterpunch, comparing Assange to Neo from The Matrix films.

Assange later attempted to disassociate himself from Shamir to reporters: “WikiLeaks works with hundreds of journalists from different regions of the world. All are required to sign non-disclosure agreements and are generally only given limited review access to material relating to their region.”

One of the things that were largely missed in the kerfuffle of the immediate Cablegate reporting, was the U.S. cables on Russia. They argued that the Russian government was so corrupt that it’s work was almost indistinguishable from the organized crime gangs, and estimated Russian political bribery totalled $300bn per year.

Despite this, or perhaps because of this, at the Cablegate launch party at the Rotunda restaurant in London, he told journalists that he was thinking of going to Russia. He would never get the chance to do so.

Shambolic Cablegate launch

The papers had agreed on a simultaneous launch at 21:30 GMT on Nov 28, 2010. However, one of Der Spiegel’s distribution vans accidentally set off to Switzerland a day early, and a batch of 40 copies of Der Spiegel arrived at Basel station in the early hours of the morning.

This was noticed by an anonymous Twitter user with the handle Freelancer_09 who began tweeting the magazine’s contents to the world. Panicked Der Spiegel journalists tried to contact the mysterious tweeter to get him to stop posting, but he just ignored them.

Swiss anarchist on Twitter, angry at a “Police state”

By 6pm the papers agreed that the previously agreed embargo time was effectively dead, and began to publish:

- The Guardian: “US cables leak sparks global diplomatic crisis“

- NYT: “Leaked Cables Uncloak U.S. Diplomacy“

- El Pais: “Clinton inquired about the physical and mental health of the Argentine president” [trans.]

- Le Monde: “WikiLeaks revelations behind the scenes of US diplomacy” [trans.]

- Der Spiegel: “Secret deposits reveal the worldview of the United States” [trans.]

The two foremost stories that The Guardian and NYT ran with were that Arab leaders had been urging an air strike on Iran, and that US officials had been instructed to spy on the UN's leadership, breaching three of the founding treaties of the UN.

The two foremost stories that The Guardian and NYT ran with was that Arab leaders had been urging an air strike on Iran, and that US officials had been instructed to spy on the UN's leadership, breaching three of the founding treaties of the UN.

- Nov 30: “How Washington sees the fight against terrorism in France” [trans.] (Le Monde)

- Dec 1: “The Spanish do not object to secret CIA flights” [trans.] (El Pais)

- Dec 1: “How US worked to get three soldiers off the hook for cameraman's death” [trans.] (El Pais)

- Dec 2: “US embassy cables vindicate Litvinenko murder claim” (The Guardian)

- Dec 2: “Skimming Off the Top: US army charged fees for Afghanistan donations” [trans.] (Der Spiegel)

- Dec 2: “US Diplomats Analyzed Death Of Bruno the Bear” [trans.] (Der Spiegel)

- Dec 3: “US Ambassador Seeks to Limit Fallout from Cables” [trans.] (Der Spiegel)

- Dec 3: “Conservatives promised to run ‘pro-American regime'” (The Guardian)

- Dec 3: “Cable Depict Afghan Graft, Starting at Top” (NYT)

- Dec 4: “WikiLeaks cables blame Chinese government for Google hacking” (The Guardian)

- Dec 4: “Don’t Look, Don’t Read: Government Warns Its Workers Away From WikiLeaks Documents” (NYT)

- Dec 5: “Vast Hacking by a China Fearful of the Web” (NYT)

Assange did a Live Q&A answering questions on his Australian citizenship, UFOs (apparently there are references to them in the Cablegate archive), threats on his life (calling for incitement to commit murder charges), and on Manning, whom he called “an unparalleled hero.”

A former British diplomat accused him of undermining the entire process of diplomacy, arguing “diplomacy cannot operate without discretion and the protection of sources. This applies to the UK and the UN as much as the US.” Assange simply dismissed this as “a vast editorial letter.”

The Wikileaks Cablegate Backlash

The State Department denounced the release of some of the cables as a “reckless and dangerous action.” Joe Klein wrote for TIME magazine announcing “Assange is a criminal.”

Former US vice-presidential candidate Sarah Palin called Assange to be “pursued with the same urgency we pursue al-Qaeda and Taliban leaders.”

Republican congressmen also voiced a desire for violent revenge: New York congressman Peter King suggested WikiLeaks be designated “a foreign terrorist organization,” Pete Hoekstra of Michigan offered “If we go after them, and are able to convict them on treason, then the death penalty comes into play” and Mike Rodgers said “I argue the death penalty clearly should be considered here.”

Despite U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s advocacy of Global Internet Freedom earlier that year, including the freedom to criticize governments without fear of retribution, she took a different tone with WikiLeaks, arguing “disclosures like these tear at the fabric of the proper function of responsible government.” Assange later agreed with this, but expressed no remorse, claiming ‘the “fabric” Clinton referred to had been woven from lies.’

The NYT responded to the mounting criticism stating “As daunting as it is to publish such material over official objections, it would be presumptuous to conclude that Americans have no right to know what is being done in their name.”

U.N. Special Rapporteur Juan Mendez defended Assange by arguing that the disclosures of torture, committed under former President George W. Bush, should be the main focus for the Obama administration.

What was emerging was not just a war of words, but war across cyberspace. Self described “hacktivist for good” The Jester apparently brought down the WikiLeaks website and tweeted “www.wikileaks.org – TANGO DOWN – for attempting to endanger the lives of our troops, ‘other assets’ & foreign relations.”

Assange moved the main website onto Amazon’s EC2 Elastic Cloud Computing service. This service allows the number of servers to increase as demand on the website increases, thereby allowing WikiLeaks to withstand ongoing denial of service attacks on its website.

The company EasyDNS provided the service of translating Wikileaks Server’s IP address into the human readable www.wikileaks.org but terminated this. WikiLeaks then changed its address to www.wikileaks.ch registered in Switzerland and hosted in a Swedish nuclear bunker. Swedish hosting firm PRQ said “If it is legal in Sweden, we will host it, and will keep it up regardless of any pressure to take it down.”

WikiLeaks financing was also suffocated. PayPal suspended the WikiLeaks account due to “violation of the PayPal acceptable use policy.” MasterCard and Visa also cut off service to the organization, and PostFinance closed Assange’s bank account on the basis that he was not living in Geneva.

The “hacktivist” group Anonymous then launched “Operation Avenge Assange,” and encouraged denial of service attacks on the organizations that it deemed had mistreated Assange. The group then conducted cyber attacks on PayPal, PostFinance, EveryDNS, Visa, Mastercard and the website of U.S. Senator Joe Lieberman.

WikiLeaks’ Twitter account quoted Cyberlibertarian activist John Perry Barlow: “The first serious infowar is now engaged. The field of battle is WikiLeaks. You are the troops.”

Two teenagers were arrested in The Netherlands for illegal use of the Low Orbit Ion Cannon, but it is probable that most of the perpetrators were never caught.

Arrest of Assange

After hearing about his Interpol arrest warrant for sex crimes, Assange agreed to meet the Metropolitan Police extradition unit on the morning of Dec 6, 2010. The officers arrested him, explaining that they were acting on behalf of the Swedish authorities.

Assange’s piece for The Weekend Australian “Don’t shoot messenger for revealing uncomfortable truths” was published the following evening. He listed the various threats made against him and his son, and criticized the Australian and US governments saying they didn’t want the truth to be revealed.

At the City of Westminster Magistrates’ Court in London, Judge Riddle explained to the court that the case was not about WikiLeaks, it was about alleged sex crimes in Sweden. Assange stated that he did not consent to the extradition to Sweden.

When asked for his address, he replied “PO Box 4080” amusing the gallery but not the judge. Riddle refused bail on the grounds that he might flee, and Assange was put in a van and taken to Her Majesty’s Wandsworth Prison. Assange had previously compared himself with his hero Alexandr Solzhenitsyn, and now he had finally gained something in common with him: time spent in a prison cell.

On the arrest of Assange, US Defence Secretary Gates told reporters “that sounds like good news to me.” Prosecutors in Sweden said they “have not been put under any kind of pressure, political or otherwise,” but Assange’s lawyer Mark Stephens speculated “many believe the prosecution is politically motivated” and implied (without evidence) that Assange has been the victim of some sort of setup.

Meanwhile, the Cablegate news stories kept coming out thick and fast:

- Dec 6: “WikiLeaks cables claim al-Jazeera changed coverage to suit Qatari foreign policy” (The Guardian)

- Dec 6: “This is how the United States sees them” [trans.] (El Pais)

- Dec 7: “U.S. Strains to Stop Arms Flow” (NYT)

- Dec 7: “US diplomats point to Ben Ali's “sclerotic” regime in Tunisia” [trans.] (Le Monde)

- Dec 7: “Washington fights to rebuild battered reputation” [trans.] (Der Spiegel)

- Dec 8: “US Attempts to Influence World Climate Body” [trans.] (Der Spiegel)

- Dec 9: “Pfizer ‘used dirty tricks to avoid clinical trial payout'” (The Guardian)

- Dec 10: “Serbia suspects Russian help for fugitive Ratko Mladić” (The Guardian)

- Dec 13: “Drive to tackle Islamists made ‘little progress'” (The Guardian)

- Dec 15: “WikiLeaks: torture and totalitarianism, daily life in Eritrea, a country adrift” [trans.] (Le Monde)

- Dec 16: “India accused of systematic use of torture in Kashmir” (The Guardian)

- Dec 17: “US Pressured Italy to Influence Judiciary” [trans.] (Der Spiegel)

On Dec 11, 2010, The Telegraph called Assange the most dangerous man in the world

and quoted Daniel Domscheit-Berg, the most high-profile WikiLeaks volunteer to abandon the organization in disgust.

Domscheit-Berg said “I felt that he betrayed the things for which WikiLeaks should stand. There was too much hype around Assange and the political conflicts of the organisation, and less around published contents. The basic idea of the organization was originally that the public and media get access to the information. But WikiLeaks, in deciding which parts of the media get the information, has taken sides subjectively. It has created a market where money is changing hands.”

Assange Bailed

Assange made a second court appearance on Dec 14, where his barrister Geoffrey Robertson QC told the court the idea that he would try to escape after being granted bail was preposterous.

The grant of bail was appealed by the Crown Prosecution Service and referred to the high court, which heard that Assange might not flee the country but simply vanish in the UK. Robertson ridiculed this idea: “Is it really suggested that Mr Michael Moore is going to slip through customs wearing a baseball cap, go to Norfolk in the middle of the night and plan to transport this gentleman we know not where?”

mock the idea of an Assange escape, shortly before Assange escaped.

Photo by Nicolas Genin from Paris, France, CC BY-SA 2.0

Assange was freed on bail on Dec 16 after a payment of £240,000 in cash and sureties and on condition he resides at Ellingham Hall, Norfolk. Robertson jokingly called it a “mansion arrest,” since his lodgings were about to be significantly upgraded to a Georgian mansion.

He was offered surety by several supporters, including Vaughan Smith, someone who knows a lot about living dangerously. A former captain of the Grenadier Guards, he later became a freelance video journalist with Frontline TV. Smith was shot twice while filming in Kosovo and survived thanks to a mobile phone he had on him, which stopped a sniper’s bullet.

Smith explained his decision to help Assange: “Having watched him give himself up last week to the British justice system, I took the decision that I would do whatever else it took to ensure that he is not denied his basic rights as a result of the anger of the powerful forces he has enraged.”

Although the court hearings were considering extradition to Sweden, Australian journalist and Assange supporter John Pilger warned “we should be looking not so much to the extradition to Sweden but to the US. It’s the great unspoken in this case. The spectre we are all aware of is that he might end up in some maximum security prison in the US.” Assange was even more bleak, telling reporters “I would have a high chance of being killed in the US. prison system, Jack Ruby style, given the continual calls for my murder by senior and influential US politicians.”

On Dec 14, 2010 the US Department of Justice issued secret subpoenas for the Twitter accounts of Manning, Jonsdottir, Assange, as well as programmers Rop Gonggrijp and Jacob Appelbaum.

The subpoena was unsealed by a Jan. 5, 2011 court order at the request of Twitter’s lawyers, and the NYT published the story soon after. WikiLeaks suggested that Google and Facebook might also have been issued subpoenas. Facebook declined to comment, and Google did not immediately respond to an NYT inquiry.

In 2011, while Assange’s legal appeals were proceeding, he decided to sign a TV deal with Russia Today. The Julian Assange Show described itself as a “on a quest for revolutionary ideas,” and interviewed a variety of guests from around the world discussing political issues.

Full Unredacted Leak

The reporting of the cables had included redactions in order to protect the US diplomats’ informants. But by August 2011, a series of blunders led to the entire unedited, unredacted cables being released, complete with the sensitive names from Iran, China, Afghanistan and the Arab world.

Assange originally gave a password to Ian Traynor of The Guardian, for decrypting the cables. Assange also stored the encrypted data in a hidden data file on the WikiLeaks server. In the book “Inside Julian Assange’s War on Secrecy,” David Leigh and Luke Harding describe Assange handing a password on a napkin:

“Assange had insouciantly circled several words and the hotel’s logo on the Hotel Leopold napkin adding the phrase “no spaces”. This was the password. In the corner he scrawled three simple letters: GPG. GPG was a reference to the encryption system he was using for a temporary website. The napkin was a perfect touch, worthy of a John le Carre thriller.”

In August 2011 information on the hidden file and the password were published on an online forum. Assange blamed both The Guardian and his former colleague Daniel Domscheit-Berg, alleging “By mid-August we discovered that a former German employee – whom I had suspended in 2010 – was cultivating business relationships with a variety of organizations and individuals by shopping around the location of the encrypted file, paired with the password’s whereabouts in the book. At the rate the information was spreading, we estimated that within two weeks most intelligence agencies, contractors, and middlemen would have all the cables, but the public would not.”

Assange decided to publish the full unredacted cables and to give the State Department advance warning of his new plan. WikiLeaks’ Sarah Harrison called the State Department front desk and told the operator that Assange wanted to speak with Hillary Clinton. While Clinton never took the call, WikiLeaks eventually reached her senior legal advisor.

The Wikileaks' Twitter account then called on users to vote on whether they agreed with the publication of the unredacted cables, using the hashtags “WLVoteYes” or “WLVoteNo”.

After the cables were published in full, The Guardian rebuffed Assange’s accusation that they were at fault, stating “no concerns were expressed when the book was published and if anyone at WikiLeaks had thought this compromised security they have had seven months to remove the files.”

Commenting on the full unredacted publication, Der Spiegel concluded: “A chain of careless mistakes, coincidences, indiscretions and confusion now means that no potential whistleblower would feel comfortable turning to a leaking platform right now. They appear to be out of control.” [trans.]

Assange Breaches Bail

In 2012, Britain’s Supreme Court ruled that Assange should be extradited to Sweden to face allegations of sexual assault. Assange’s final appeal option was to apply to the European court of human rights in Strasbourg, but Assange decided against this and took another action that virtually no one expected.

On 19 June 2012, the Ecuadorian foreign minister, Ricardo Patiño, announced that Assange had applied for political asylum, that his government was considering the request, and that Assange was at the Ecuadorian embassy in London.

British police were tasked with arresting Assange, but under the Vienna Convention they were not allowed to enter the building to arrest him, and reduced to sending him a letter requesting that he leave the building and report to the police station.

Assange refused to comply with this, and in August UK-Ecuadorian relations were strained further when political asylum was granted to Assange. Ecuador declared “as a consequence of Assange’s determined defense to freedom of expression and freedom of press … in any given moment, a situation may come where his life, safety or personal integrity will be in danger.”

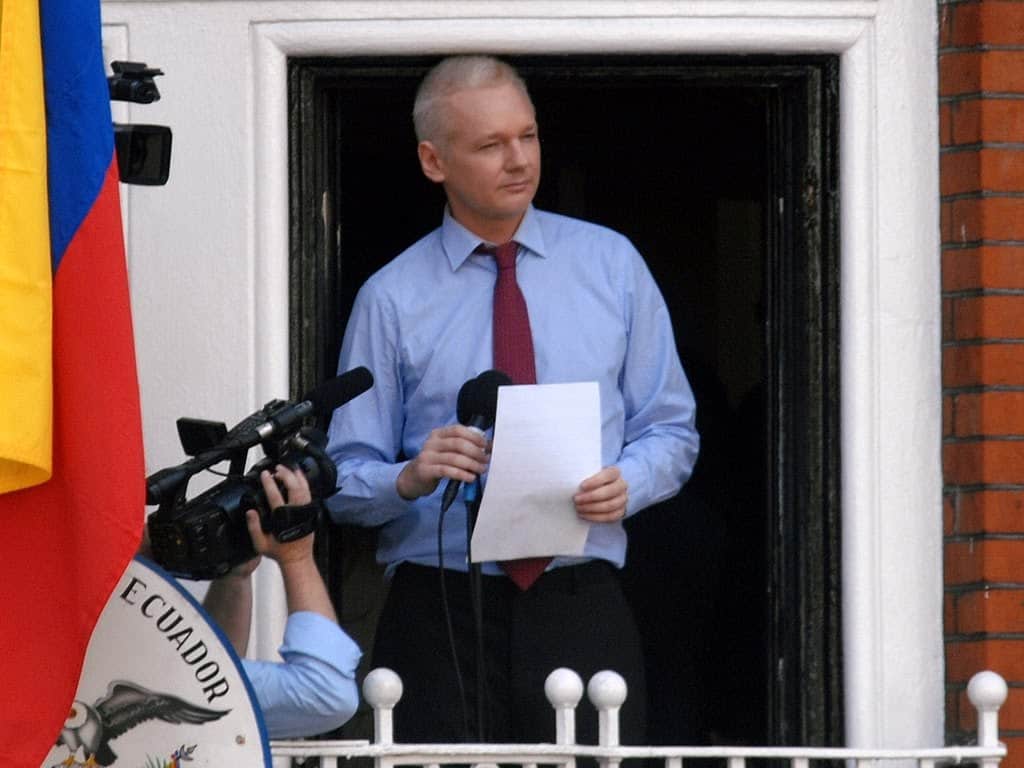

Photo by Snapperjack from London, UK. CC BY-SA 2.0

On the 19th August 2012, Assange gave a triumphant public address from the balcony of the embassy, arguing that freedom of expression was under threat and telling president Obama to “renounce its witch hunt against WikiLeaks.”

In this episode we have covered the WikiLeaks story in the years 2010 through to 2012. Over this period, and the years that followed up until this day, opinions have remained divided on Assange’s guilt or innocence, and raised many questions on freedom of expression and national security.

In the next episode, we cover the biggest news story of 2013, Edward Snowden.