“The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.” —Fourth Amendment, United States Bill of Rights, 1789

“Any citizen of the United States who is not involved in some illegal activity has nothing to fear whatsoever.” —John Mitchell, United States Attorney General, 1969

For the past few episodes we have been examining the history of the internet within the context of government regulation. The internet was born decades before the World Wide Web, in the United States Department of Defense in 1969, a year remembered for both its amazing technological progress, and for its civil rights movement.

In Part 17 we learned that the Fourth Amendment was written in response to actions of the British government in America in the days before it won its independence. The British government had a culture of secrecy and intrusion that included the covert opening of mail and routine searches of property.

The founders deemed this to be wholly unreasonable and wrote the Fourth Amendment in the belief that it would abolish the power of the government to subject its citizens to generalized, suspicionless surveillance.

Part 17 also covered the Watergate scandal, project SHAMROCK and COINTELPRO. These and other abuses led to the enactment of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978, which generally requires the government to seek warrants before monitoring Americans’ communications.

In Part 20 we covered the 9/11 atrocity and the subsequent actions of the United States government: the USA Patriot Act and a new warrantless wiretapping program. This program was ratified and expanded by the FISA Amendments Act of 2008, which the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and Amnesty International filed a lawsuit against. Amnesty v. Clapper claimed that the FISA Amendment Act was unconstitutional.

Rather than argue the constitutionality of the surveillance activities that the act granted, the U.S. government successfully argued that the ACLU’s clients were unable to prove that they had been surveilled.

The ACLU was unable to seek the necessary evidence because, if it were the case that the clients had been surveilled, then that evidence would be a “state secret.” A judge in New York dismissed the suit in 2009, but in 2012 the case was heard by the U.S. Supreme Court.

While the Supreme Court was considering the case, the FISA Amendment Act was shortly due to expire, and Congress voted to extend it for five more years. President Barack Obama signed the bill into law on Dec. 30, 2012.

First Contact

On Dec. 1, 2012, the American journalist, former constitutional law and civil rights lawyer, NSA critic, and WikiLeaks supporter Glenn Greenwald received a mysterious email from someone calling himself “Cincinnatus.”

The email began, “The security of people’s communications is very important to me.” It urged Greenwald to install the Pretty Good Privacy (PGP) encryption software so that he could receive information that would be of interest to him. “Encryption matters, and it is not just for spies and philanderers,” read the email. Greenwald ignored it.

Three days later Greenwald received a chaser email from the mysterious Cincinnatus. This time Greenwald replied, “I got this and am going to work on it. I don’t have a PGP code, and don’t know how to do that, but I will try to find someone who can help me.” He received a step by step guide to PGP in another email, which signed off “Cryptographically yours, Cincinnatus.”

Seven weeks later, guilt over his inaction prompted Greenwald to respond to his contact again, telling him he would find someone to help him with the encryption soon. Cincinnatus sent a 10-minute video titled “PGP for Journalists.” Again, Greenwald ignored it.

While Cincinnatus was gradually getting more frustrated with Greenwald’s inaction, the Supreme Court delivered its ruling.

Clapper v. Amnesty International USA Ruling

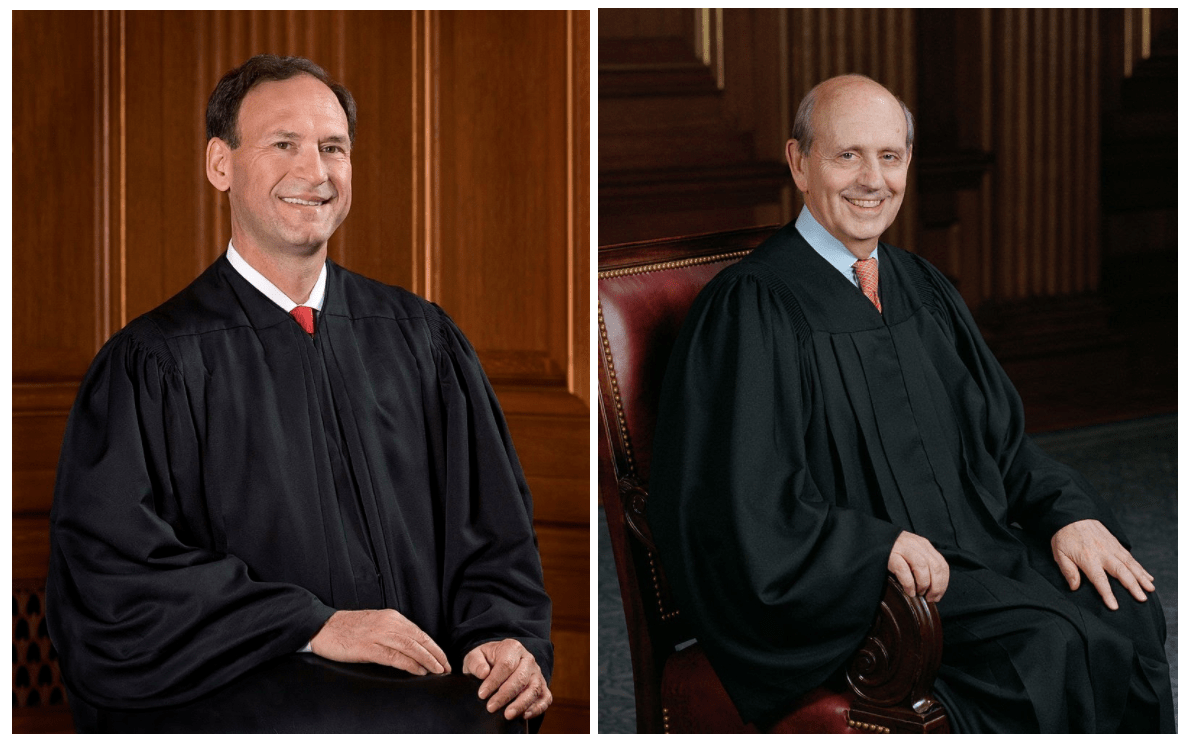

On Feb. 26, 2013, the U.S. Supreme Court decided, in a 5 to 4 ruling, in favor of the U.S. government.

Justice Samuel Alito, one of the five judges who ruled in favor of the government, wrote, “Respondents cannot manufacture standing merely by inflicting harm on themselves based on their fears of hypothetical future harm that is not certainly impending.” Justice Breyer wrote in dissent that government spying was “as likely to take place as are most future events that common-sense inference and ordinary knowledge of human nature tell us will happen.”

Nearly 5,000 miles west of Washington, D.C., Cincinnatus was living on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, when he heard the Supreme Court ruling. Unlike most of his colleagues in the intelligence community, he was appalled by the verdict.

Greenwald Meets Poitras

The filmmaker Laura Poitras began receiving emails from someone using the pseudonym “citizenfour” in January 2013:

“You asked why I picked you. I didn’t. You did.

“The surveillance you’ve experienced means you’ve been ‘selected’ — a term which will mean more to you as you learn about how the modern SIGINT system works.

“For now, know that every border you cross, every purchase you make, every call you dial, every cell phone tower you pass, friend you keep, article you write, site you visit, subject line you type, and packet you route is in the hands of a system whose reach is unlimited but those safeguards are not.”

By April 2013, Greenwald received an email from Poitras asking for a meetup. He met her the next day at his hotel restaurant. Poitras told him she had an “extremely important and sensitive matter” to discuss, and asked him to either remove the battery from his phone or leave it in his hotel room.

Greenwald dropped off his phone in his hotel room and returned to Poitras. She told him she’d received emails from “citizenfour” claiming to have access to extremely secret and incriminating documents about the U.S. government spying on its own citizens and on the rest of the world.

Poitras produced printouts of two of these emails. After reading them, Greenwald replied, “He’s real. I can’t explain exactly why, but I just feel intuitively that this is serious, that he’s exactly who he says he is.”

Or was he? He could be a fantasist wasting their time, or perhaps someone trying to damage their credibility by inducing them into publishing fraudulent documents? Greenwald and Poitras discussed the risks but ultimately agreed that they believed him to be genuine.

Greenwald flew back to his home in Rio de Janeiro and later received (after an unexplained customs delay) two USB thumb drives in the post. Using the software on the thumb drives he communicated with Poitras online using OTR messaging encryption to prevent unwanted snoopers. Poitras told him they needed to fly to Hong Kong to meet their source.

Verax

Greenwald soon also received an email from the source, who was named Verax, Latin for “truth teller” and a play on Julian Assange’s original pseudonym, “Mendax,” which means “speaker of lies.”

The email read, “Is there any way we can talk on short notice? I understand you don’t have much in the way of secure infrastructure, but I’ll work around what you have.”

Greenwald learned that the source was concerned with what had happened at The Washington Post: Poitras had given a reporter some NSA documents, but instead of quickly publishing a story on it, they seemed to have gotten frightened by what the lawyers were telling them.

“I don’t like how this is developing,” the source told Greenwald. “I’ve been reading you a long time, and I know you’ll be aggressive and fearless in how you do this.”

“I’m ready and eager,” replied Greenwald.

“The first order of business is for you to get to Hong Kong,” said Verax.

Greenwald’s husband advised him, “Tell him that you want to see a few documents first to know that he’s serious and that this is worth it for you.” After Greenwald installed more security programs, Verax sent a file containing approximately 25 documents, each marked “TOP SECRET//COMINT//NOFORN.” Greenwald was overwhelmed by the information they contained.

Greenwald called Janine Gibson, the British editor of the US edition of The Guardian via Skype and blurted out, “Janine, I have a huge story. I have a source who has access to what seems to be a large amount of top secret documents from the NSA.”

Gibson soon stopped him, saying, “I don’t think we should talk about this on the phone, and definitely not by Skype.”

Greenwald flew back to New York to show the documents he had to Gibson, and her deputy, Stuart Millar. Gibson concluded, “You need to go to Hong Kong as soon as possible, like tomorrow, right?” She insisted that he be joined by longtime Guardian reporter Ewan MacAskill, on the condition that MacAskill would not meet the source until both Greenwald and Poitras gave the go-ahead.

As Greenwald and Poitras arrived together at JFK Airport for their flight to Hong Kong, Poitras pulled another thumb drive out of her backpack.

“Guess what this is?” she asked.

“What?” replied Greenwald.

“The documents. All of them”

On the flight to Hong Kong, Greenwald noticed the source had included a file named “README_FIRST,” which revealed the source’s name, Edward Joseph Snowden, as well as his anti-authoritarian motive for committing such a serious crime:

“When marginalized youths commit minor infractions, we as a society turn a blind eye as they suffer insufferable consequences in the world’s largest prison system, yet when the richest and most powerful telecommunications providers in the country knowingly commit tens of millions of felonies, Congress passes our nation’s first law providing their elite friends with full retroactive immunity.”

Snowden was the real identity behind the pseudonyms Cincinnatus, citizenfour, and Verax. He had selected Poitras and Greenwald because of their earlier work criticizing the national security “state.”

Hong Kong Interview

After arriving in Hong Kong, Poitras and Greenwald received a message inviting them to meet him at his hotel the next morning, on June 3, 2013. They were instructed to visit a specific conference room and ask the first nearby hotel employee whether there was a restaurant open, and wait on a couch, near a giant plastic alligator!

The restaurant question was a coded message to Snowden, who was discreetly standing nearby, that they had not been followed. “How will we know it’s him?” asked Greenwald. “He’ll be carrying a Rubik’s Cube,” answered Poitras.

When Snowden arrived, and holding the promised Rubik’s Cube, Greenwald was stunned by how young their source was. At just 29 years, he was surely risking a large proportion of his remaining life behind bars. He told Snowden he’d expected someone much older, perhaps someone in the final months of their life. “So, come with me,” said Snowden, and he walked them into an elevator. They got off on the 10th floor and walked into Room 1014.

Snowden then insisted they remove their phones’ batteries and put them in the minibar refrigerator. He warned them that the U.S. government had the capability to remotely activate phones and convert them into listening devices. He then placed his bed pillows at the foot of the door, in case anyone was trying to listen in from the hallway.

Poitras took out her video camera and began filming Snowden. Although this was done with his agreement, as someone who lived to evade surveillance, the irony was not lost on Snowden, and he stiffened.

He later described the experience as a “surreal dynamic” and likened the red light on the camera to a sniper’s sight. Snowden was initially reluctant to talk too much about himself because he feared it could be used as a distraction from the secret material that he wanted to expose.

As a former lawyer, Greenwald was experienced in taking witness depositions, and took this approach in the interview, questioning him for five hours, and assessed him to be intelligent and rational. Snowden said he had real concerns about a lack of oversight and accountability in the NSA beginning in 2009, but had hoped that the election of Barack Obama would reform what he considered to be their worst abuses.

“But then it became clear that Obama was not just continuing, but in many cases expanding these abuses. I realized then that I couldn’t wait for a leader to fix these things.”

In response to questioning about his motivation for revealing classified information, Snowden cited Joseph Campbell’s book The Hero with a Thousand Faces as a childhood influence which taught him, “It is we who infuse life with meaning through our actions and the stories we create with them.”

Another important influence on Snowden was the internet: “The internet allowed me to experience freedom and explore my full capacity as a human being. For many kids, the internet is a means of self-actualization. It allows them to explore who they are and who they want to be, but that only works if we’re able to be private and anonymous, to make mistakes without them following us. I worry that mine was the last generation to enjoy that freedom. I do not want to live in a world where we have no privacy and no freedom, where the unique value of the internet is snuffed out.”

Greenwald asked him why he’d chosen to fly to Hong Kong? Snowden replied that American agents would find it harder to operate against him there. He preferred Hong Kong over mainland China because Hong Kong had greater political freedoms, though he was aware that he could still be smeared as a Chinese double agent.

Snowden predicted, “They’ll say I violated the Espionage Act. That I committed grave crimes. That I aided America’s enemies. That I endangered national security. I’m sure they’ll grab every incident they can from my past, and probably will exaggerate or even fabricate some, to demonize me as much as possible.”

That evening Greenwald drafted four articles based on Snowden’s information: one on the secret FISA court order compelling Verizon to give the NSA all of their telephone records, one on the history of President George W. Bush’s warrantless eavesdropping program, one on BOUNDLESS INFORMANT, and one on the PRISM program.

Greenwald then messaged Janine Gibson, pushing her to publish as soon as possible. Gibson replied that her lawyers were worried: “They’re saying that the FBI could come in and shut down our office and take our files.”

The next day, Poitras and Greenwald brought MacAskill along with them to meet Snowden. MacAskill questioned him for about two hours, checked over his diplomatic passport and other government ID, and concluded, “I’m completely convinced he’s real.”

Verizon Story Publication

In New York, Gibson called the NSA and the White House to inform them they were planning to publish top secret material. However, this was the morning that Susan Rice was named as its new National Security adviser. Gibson believed this to be the reason for a delay in returning her calls.

At around 3pm she received a conference call from many agencies including the NSA, DOJ, and the White House, who warned her, “no normal journalistic outlet would publish this quickly without meeting with us.”

Gibson was also under pressure from Greenwald, who insisted that if they didn’t publish that day he would publish the story with another organization, such as Salon or The Nation, or even self-publish the information online. Gibson agreed and published NSA collecting phone records of millions of Verizon customers daily. The ACLU responded arguing that “the program could hardly be any more alarming” and calling it “beyond Orweillian.”

The story was quickly picked up by CNN, who contacted Greenwald to arrange an interview with Jake Tapper. Greenwald explained:

“It’s important because people have understood that the law that this was done under, which is the PATRIOT Act enacted in the wake of 9/11, was a law that allowed the government very broad powers to get records about people with a lower level of suspicion and probable cause than traditional standards. So it has always been assumed that under the PATRIOT Act, if the government had any suspicion that you were involved in a crime or terrorism, they could get a lot of information about you.

“What this court order does that makes it so striking, is that it’s not directed at any individuals who they believe or have suspicion of committing crimes or part of a terrorist organization. It’s collecting the phone records of every single customer of Verizon business and finding out every single call they’ve made internationally and locally. So it’s indiscriminate and it’s sweeping.”

That evening Greenwald returned to Snowden, who said, “Everyone thinks this is a one-time story, a stand-alone scoop. Nobody knows this is just the very tip of the iceberg.”

PRISM

The following day, on June 5, 2013, Poitras and Barton Gellman break the PRISM story in The Washington Post, revealing that the NSA had secret access to the data of all the major internet companies: Microsoft, Yahoo, Google, Facebook, AOL, Skype, YouTube, and Apple.

All of the communications of any non-American, including those with U.S. citizens, including all emails, social media activity, and internet searches, could be obtained from those companies on demand.

The Guardian followed 10 minutes later with Greenwald’s piece on the same story, but with an emphasis on the denials of the internet companies. As with the Verizon story, they contacted the government beforehand, but with this story they also contacted the internet companies, who responded that they had never heard of PRISM.

CNN immediately covered the story as breaking news, with the former NSA official William Binney commenting that he wasn’t surprised because it was a continuation of what they had been doing while he worked there.

Former White House Press Secretary Ari Fleischer defended the program, saying, “I don’t want us to drop our guard. I don’t want us to be struck again, like we saw in Boston,” and arguing, “people are willing to sacrifice their civil liberties.”

Some reporters were also highly critical of Greenwald. The New York Times published a belittling article titled “Blogger, with Focus on Surveillance, Is at Center of a Debate,” claiming Greenwald “is expected to attract an investigation from the Justice Department, which has aggressively pursued leakers” and quoted Gabriel Schoenfeld’s characterization of him as “a highly professional apologist for any kind of anti-Americanism no matter how extreme.”

A reporter from the New York Daily News emailed, informing him he was being investigated for past debts, tax liability, and past investment in an adult video distribution company. Coincidentally or otherwise, Michael Schmidt for the New York Times contacted him regarding the same previous tax debt on the same day.

Greenwald returned to CNN to argue, “The fact that there are no checks, no oversight about who’s looking over the NSA’s shoulder, means that they can take whatever they want, and the fact that it’s all behind a wall of secrecy and they threaten people who want to expose it means that whatever they’re doing, even violating the law, is something that we’re unlikely to know until we start having real investigations and real transparency into what it is the government is doing.”

Snowden had set up an internet security device at his home, which notified him that two people from the NSA had come searching for him. At this point, he felt they already suspected him to be the source of the leaks, and that it would not be long before they tracked down his location.

Greenwald, Poitras, and MacAskill agreed with Snowden that after another two articles had been published, they would reveal him as the source of the leaks.

Reveal and Escape: Living as a Fugitive

Poitras recorded a video of Snowden revealing himself as the source of the leaks, and posted “Edward Snowden: the whistleblower behind the NSA surveillance revelations” on June 9, 2013.

In Hawaii, Snowden’s girlfriend, Lindsay Mills, was shocked to receive a call from a friend, who told her there was a video of Snowden on the homepage of The Huffington Post. She wrote in her diary: “I calmly waited for the 12-minute YouTube video to load. And then there he was. Real. Alive. I was shocked.”

In the Ecuadorian embassy in London, Julian Assange watched Snowden’s video with interest, and then instructed his WikiLeaks colleague, Sarah Harrison, to fly out to Hong Kong to try to find him.

The next day, Pentagon Papers whistleblower Daniel Ellsberg praised Snowden, arguing, “There has not been in American history a more important leak than Edward Snowden’s release of NSA material — and that definitely includes the Pentagon Papers 40 years ago.”

Greenwald then received an urgent early morning call from a contact in Hong Kong: “We’re already here,” the man said, “downstairs in your hotel. I have the two lawyers with me. Your lobby is filled with cameras and reporters. The media is searching for Snowden’s hotel and will find it imminently, and the lawyers say that it’s vital they get to him before the media finds him.”

After throwing on the first clothes he could find, Greenwald opened his hotel door to find flashes from multiple cameras aimed at him. Reporters from the Wall Street Journal and Associated Press followed him into the elevator, and when he reached the lobby he found even more reporters, so many that he could not find the lawyers who needed to find Snowden.

After giving an impromptu press conference in the lobby, the reporters mostly dispersed, and Greenwald found two Hong Kong lawyers and the Guardian’s chief lawyer, Gill Phillips. They contacted Snowden via encrypted chat, and Snowden informed them, “I am in the process of changing my appearance, I can make myself unrecognizable.”

The next problem was how to get the lawyers out of Greenwald’s hotel without them being followed by reporters, some of whom were waiting right outside the hotel room. Greenwald and Phillips lured the reporters back down to the lobby, and after a few minutes the Hong Kong lawyers snuck out undetected.

The lawyers took him to one of the city’s poorest neighborhoods and introduced him to some refugees from Sri Lanka and the Philippines, who agreed to help him. Greenwald received a message from Snowden later that day saying, “In a safe house for now. But I have no idea how safe it is, or how long I’ll be here. I’ll have to move from place to place, and my internet is unreliable, so I don’t know when or how often I’ll be online.”

Back in Hawaii, Lindsay Mills received a call from her lawyer advising her to meet with the FBI, in the first of several meetings. Two agents questioned her relationship with Snowden, and she was informed that she would be followed by the FBI 24/7 for the foreseeable future.

On June 14, the U.S. government charged Snowden under the Espionage Act under a sealed complaint.

June 20, the U.K. government pressured The Guardian to destroy the GCHQ archive given to Ewan MacAskill in Hong Kong.

On June 21, the U.S. government formally requested his extradition. Snowden wiped his laptops clean and destroyed his decryption key, so that he could not access any of the classified documents.

His lawyers advised him that Ecuador would be the most likely country to defend his right to political asylum. He was also advised to try to obtain a laissez-passer, which is a UN-recognized, one-way travel document issued to grant safe passage to refugees.

Around this time, Snowden was introduced to WikiLeaks’ Sarah Harrison through Poitras. They corresponded electronically for a day or two before meeting in person. Harrison arranged for the Ecuadorian consul in London to produce a laissez-passer, which she gave to Snowden. She also hired a van to take him to the airport.

Russia

Harrison and Snowden arrived at Sheremetyevo on June 23 for what they expected to be a 24-hour layover. According to Snowden, he was stopped at passport control, with the officer telling him, “There is problem with passport. Please, come with.”

Snowden says he told the officers, “I’m not going to cooperate with any intelligence service,” before they explained that his passport had been revoked: “It is the decision of your minister, John Kerry. Your passport has been canceled by your government, and the air services have been instructed not to allow you to travel.”

From the airport, Snowden applied to 27 countries for political asylum. All declined, except Russia who granted Snowden temporary asylum on Aug. 1, 2013. This asylum has since been extended, and Snowden remains in Russia to date.

Hero or Traitor?

The Snowden leaks significantly shifted public opinion on privacy issues. At the end of July 2013, the Pew Research Center released a poll showing “a majority of Americans — 56% — say that federal courts fail to provide adequate limits on the telephone and internet data the government is collecting as part of its anti-terrorism efforts.” And “an even larger percentage (70%) believes that the government uses this data for purposes other than investigating terrorism.”

At a press briefing in June 2013, President Obama said, “I don’t think Mr. Snowden was a patriot. I called for a thorough review of our surveillance operations before Mr. Snowden made these leaks. My preference, and I think the American people’s preference, would have been for a lawful, orderly examination of these laws.”

At the 2016 Democratic Party debates, presidential candidates were asked, “Is former National Security Agency contractor and whistleblower Edward Snowden a hero for revealing the American government’s massive surveillance program or a traitor who betrayed his own country?”

Former Maryland Governor and Baltimore Mayor Martin O’Malley was the most critical, saying, “Snowden put a lot of Americans’ lives at risk. Snowden broke the law. Whistleblowers do not run to Russia and try to get protection from Putin. If he really believes that, he should be back here.”

Secretary of State Hilary Clinton replied, “He broke the laws of the United States. He could have been a whistleblower. He could have gotten all of the protections of being a whistleblower. He could have raised all of the issues that he has raised. And I think there would have been a positive response to that.”

Senator Bernie Sanders responded, “I think Snowden played a very important role in educating the American people to the degree in which our civil liberties and our constitutional rights are being considered. He did break the law, and I think there should be a penalty to that, but I do think what he did to educate us should be taken into account.”

Former Rhode Island Governor Lincoln Chafee was the only candidate arguing Snowden should return to the U.S. without facing any punishment: “I would bring him home,” he said, adding that “the American government was acting illegally, that's what the federal courts have said.”

Former Virginia Senator Jim Webb declined to label Snowden, arguing, “I would leave his ultimate judgment to the legal system. Here's what I do believe: We have a serious problem in terms of the collection of personal information in this country.”