I’ve always had somewhat of a love / hate relationship with source control.

I learned fairly quickly on in my software development career that, love it or hate it, knowing your way around source control is a pretty important part of being a programmer.

I was working on a small project at HP at the time with just one other developer.

We were working on a program to automate the testing of HP printers called AntEater.

One lovely morning, I was happily coding away and decided that I needed to get the latest updates to the code.

I was working on a few files for a new feature I was building, and my teammate, Brian, had just checked in some changes.

Not wanting to be working with outdated code, I pulled down the latest changes to my machine.

I built the application and ran it to make sure everything was working.

The application launched, but something strange was happening on my computer.

The hard drive light just kept flashing.

I could hear the whirr of the mechanical drive working hard.

It was doing something, but what?

Within minutes, an error dialog popped up on my screen followed by the dreaded blue screen of death.

My PC rebooted automatically, and I was greeted with the message “non system disk error.”

Umm, ok. Usually this meant your hard drive had crashed.

I contacted IT.

They took a look at my system and confirmed that something was really wrong. Probably the hard drive had been corrupted.

They reimaged my machine and the next day I had a brand new Windows installation.

I spent that day reinstalling and reconfiguring my development environment.

Finally, I had everything back in order, so I downloaded the latest source code for the application, along with the changes I had made on my branch, and fired up the app.

Once again, my hard drive light started flashing.

I tried to abort, but it was too late.

Seconds later, I was greeted by a reboot and a familiar message… “non system disk error.”

WTF?

What was going on?

I was pissed to say the least.

Finally it occurred to me.

I went over to Brian’s desk and looked at the changes he had committed.

He had changed a variable in a C++ header file to be initialized to the value of “C:\temp.”

He had done this so that the function he wrote would work, which had the app scan from temporary files and delete them at startup.

I had made a change in the same C++ header file, but I hadn’t merged my change yet.

So, when I pulled down his latest code, I didn’t get the newest header file that had the variable set to “C:\temp,” but I did get the code that scanned through “tempFileLocation” and deleted everything there.

Since my variable wasn’t initialized, it was defaulting to “C:\”—the root directory of my computer.

Every time I launched the app, it was recursively deleting all the files on my computer.

Source control can be so much fun.

What Is Source Control?

Source control, or version control as it’s sometimes called, is a way to keep track of different versions of files and the source code of a software project and to coordinate the efforts of multiple developers who may all be working on the same sets of files.

There are many versions and implementations of source control and source control systems, but they all have the same goal of helping you to best manage the source code of your software development project.

Why Is It Important?

Back when I first started working as a software developer, there were plenty of teams who didn’t use source control.

I’ve worked on multiple projects where the source code for a multimillion dollar system resided on a shared network folder or a floppy disk that was passed around.

Lord knows how many companies relying on this version of source control—sometimes called the sneakernet—went belly up when someone mistakenly deleted the contents of the disk or shared folder.

One of the main reasons source control is so important is because it mitigates this problem.

A team using a source control system is much less likely to “lose” their code.

Source control gives you a place to check in your code and keep it secure so that it can’t be haphazardly deleted, and it allows you to keep track of changes so that if you accidentally delete some portion of the code or make a huge mistake, you can go back and fix it.

Ever saved multiple copies of a document on your computer with different dates in the title, so that you’d be able to go back to an earlier version if you needed to?

That’s what source control can do for all the code in your application.

But source control is not just about making sure you don’t lose your source code.

You could just back things up regularly to avoid that problem.

Source control also helps you to be able to coordinate multiple developers working on the same set of files in a code base.

Without source control helping to manage the different changes developers are making, it’s very easy for developers to overwrite each other’s changes or be forced to wait until someone else is done editing a file before they can edit it.

A good source control system will allow you to work on even the same files simultaneously and then merge the changes together.

Source control also solved the problem of working on multiple versions of a software application’s code base.

Suppose that you have an application that you have released to customers and it has some bugs in it that need to be fixed, but at the same time you are working on some new features for the next version of the application and those new features aren’t quite ready yet.

Wouldn’t it be nice if you could have multiple versions of the code?

For instance, one version could be the current released version where you make bug fixes, and another version could be where you develop your new features.

And wouldn’t it be nice if you could apply the bug fixes to the version of the code that contains the new features, as well?

Source control gives you the power to do just that.

Source Control Basics

There is quite a bit to know about source control—and you certainly aren’t going to become an expert just by reading about it—but you can learn the basics.

In this next section, I’m going to give you a quick rundown of the basics of source control, followed by a few of the most common source control technologies out there, so that you can at least understand how source control generally works.

Repositories

One of the key concepts with just about all source control systems is the idea of a repository—it’s basically the place where all the code is stored.

When you are working with source code, you’ll be getting the code from the repository, working on it, and checking in your changes.

Other developers may also be doing the same.

The repository is the place where all that code comes together and where the code technically “lives.”

Different source control systems have different concepts of what repository is and might even have local repositories, but ultimately, for any code base, there has to be one central location or repository that acts as the system of record.

Checking Out Code

When you want to get a local version of the code that you can modify, you’ll need to check out code from the repository.

Older source control systems had you actually check out the code and lock the files, so only you could edit them.

Most source control systems today let you “check out” code by letting you pull down a local copy of that code onto your own machine or local repository.

This checked out code is your local copy, and changes that you make to it are only made on your machine or in your local repository.

It is only when you “check-in” or merge your code to the central repository that other developers see your changes.

Normally when you are working with source control, you’ll check out a local copy of the code base, implement new features, or make other changes to the code, and then when you are done, you’ll check that code back in and handle any conflicts which may arise from multiple developers working on the same sections of code.

Revisions

Source control systems have a concept of revisions which are the previous versions of a file that is contained within source control.

So, for example, if we have a file called foo.bar that I first create and then you later modify it and then I modify it again sometime later down the road, the source control repository will contain three different version of foo.bar.

Why is this important?

Well, for a couple of reasons.

First of all, suppose I screwed up foo.bar and you want to revert back to the version that existed before I made my changes.

Since the file is in source control, you can simply revert back to the previous revision or check out the revision and pretend like my changes never even existed.

You could also look at the revision history and compare the changes in the file over time to figure out how a file evolved by seeing what changes happened at each revision and who made them.

(I like to call this finger-pointing.)

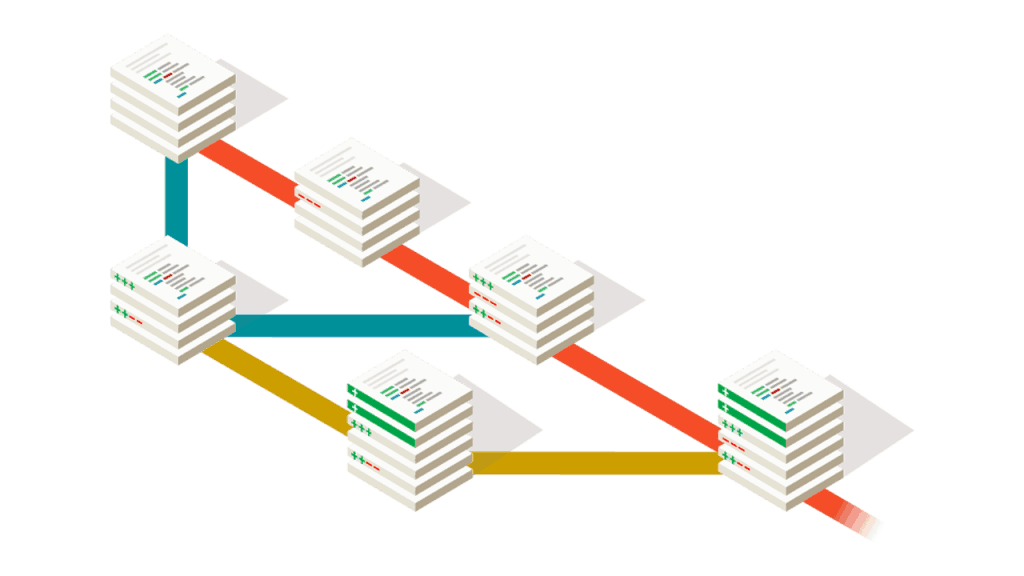

Branching

One of the most misunderstood areas of source control is branching—or rather how to use branching correctly.

The concept, though, is fairly simple.

Most source control systems allow you to create a branch off of an existing code base, in order to create a new code base that can be independently evolved from its parent.

Wait, what? I thought you said this was simple, John.

Ok, think of your code like a tree.

You’ve got the trunk, and at some point you might have multiple branches which come off of that trunk.

What does this look like in reality?

Suppose you have a version of your software that you are working on, and you are ready to ship that version to customers and call it version 1, but… you still want to continue working on new features for version 2.

The problem is—even though you are an awesome coder—you know there are going to be at least a few bugs you are going to have to fix in version 1, which you are shipping to customers.

However, you don’t want to start shipping them version 2 features when you give them bug fixes for version 1. (You are planning on charging them for an upgrade to version 2 later.)

So, what do you do?

Simple. You branch the code.

Once you are ready to ship version 1, instead of just shipping what is in the trunk, you create a new branch. You call this branch “version 1.”

Then, you can make bug fixes on the version 1 branch and implement your new features on the trunk.

Only one problem…

What if you want to get those bug fixes into the trunk as well?

Merging

Look how beautifully I set that one up.

The solution to your problem is merging.

What is merging, you may ask?

It’s exactly what it sounds like.

You are going to merge the changes from one code line into another.

In our little software example above, we simply used a merge feature of our source control system to merge our version 1 branch changes to the trunk.

Merging allows us to take all the changes we made on the version 1 branch, after we had branched from the trunk, and merge them right into the trunk.

The merge would only go one direction, so we’d get all the changes from the version 1 branch into the trunk, but none of the new features we were working on in the trunk would go into the version 1 branch.

Just as we intended.

All is well and peaceful in the world, that is until we actually try to do the merge and we find that we have…

Conflicts

F$%^!, d%&$! What is this s&$*?!

(Strangely, I don’t have any problem typing shit in this book by itself, but it seems a little inappropriate to drop three “strong” words, starting with the F-bomb, in one sentence.)

These are the kinds of words frequently uttered when developers try to do the simple, straight-forward process of merging just a few simple changes back into the trunk.

Mostly this happens on Friday evening at 5:00 PM, when you only mean to do a quick merge and get the hell out of there.

You kick off the merge, put your coat on, text your friends, and tell them where you are going to meet them for a relaxing evening of drinks and a dinner, and quickly glance at your screen to see:

“CONFLICT (content): Merge conflict in simplefile.java

Automatic merge failed; fix conflicts and then commit the result.”

Or some other such garbage.

The hours pass by as you stare at a bunch of “<<<<<” and “>>>>>” symbols in a file and try to make sense of it all.

I’m not going to lie; merge conflicts are… a bitch.

Most of the time, a good source control system will try to automatically merge simple changes made in one part of a file into another file, and it all works magically.

But… every so often, you make a change in one file on a branch, and some stupid idiot developer also makes a change in the same file on the same line—because he’s an idiot—and manual intervention is required.

The computer has no way of knowing which change should override the other one, or if both changes should somehow be included or if there is some other way to resolve the conflict, so it’s up to you.

Your Friday night is ruined.

Resolving merge conflicts and the intricacies of merging could be a whole other book by itself, so I’m not going to delve into the details here.

It’s sufficient to know for now how merging basically works, and when it doesn’t that conflicts exist which have to be manually resolved and not to do “simple merges really quickly” on Friday nights right before you are getting ready to leave.

Technologies

Source control has a pretty long and somewhat interesting history, of which are are not going to discuss here, since I lied about the interesting part.

It’s sufficient to say that source control systems evolved from passing around the source code on a USB drive, to strategically copying entire folders of source control and renaming them V1, to the fairly complex systems we have today.

Many wars were fought in source control land, and eventually two major factions emerged victorious: centralized source control and distributed.

Centralized is older. It doesn’t have quite as much “bling,” but it’s a little simpler to understand and it does the job.

CVS and Subversion are two examples of centralized source control.

Distributed is newer. It’s probably a bit shinier in most people’s eyes and it’s a bit more complicated, but more people are using it.

Git and Mercurial are two examples of distributed source control.

Centralized Source Control

With centralized source control, you have one repository, which exists on a central server that all developers working on the code utilize to get copies of the files they need and to check in changes they’ve made to files.

Each developer has a source control client that manages checking in and checking out code from the central repository.

All of the version’s history and revisions of the files are stored in the central repository.

The typical workflow for using centralized source control might look something like:

- Update my local copy of the code line I’m working on from the repository.

- Make my changes.

- Commit my changes to the central repository (and deal with any conflicts).

Distributed Source Control (DVCS)

The biggest difference with using distributed source control is that each developer has a full copy of the entire repository on their own machine.

Some really cool hipsters like to say that this means that “there is no central repository, dude. It’s like we just all have our own versions of the software, and no version is better than any others.”

This is just plain wrong.

Yes, theoretically this is possible, but how the hell are you going to ship code and coordinate a project between multiple developers if you don’t have some kind of system of record?

It’s not going to happen.

If you think it will, you should probably start your own utopia or cult or something.

The reality of the situation is that, yes, each developer has their own complete copy of the repository, but you still utilize some central version of the repository that acts as the system of record or the master repository for the project.

When you work in a distributed source control system, you simply work locally and do everything you would with a central repository system, except it happens locally.

Essentially, this means you don’t have to transfer as many files across the network, and you can work disconnected for a while.

Eventually, though, you’ve got to get changes that other people have made, and you’ve got to send your beautiful, precious changes out into the world to fend for themselves.

You do this by pulling and pushing.

With a DVCS, you can pull down changes to your local repository, and you can push changes you’ve made out to the master repository or any other repository you want—including your hipster, decentralized, every-repository-is-equal friend.

A Quick Rundown of the Most Popular Source Control Systems

If you are reading this book in the future, this list will probably change.

There is always a new source control hotness.

But, for now, at the time of writing this book, I thought I’d give you a brief introduction to the most common source control systems you are likely to see in the wild.

Caution: it’s brief.

CVS

No, it’s not a drug store. It’s source control.

It’s known as CVS or Concurrent Versions System. (I’ve never called it by the full name; I actually had to look that up.)

What is it?

Well, I know some people will get pissed when I say this, but in my opinion it’s the precursor to Subversion.

CVS is a centralized source control system, and it is fairly robust.

It’s pretty powerful, but a bit slow.

Most organizations that were using CVS eventually switched to Subversion, but CVS still handles some things a little differently and some people prefer those differences.

Tagging and branching, for example, as well as rolling back commits are handled differently in CVS.

CVS zealots will tell you CVS does it right, and Subversion does it wrong.

I don’t really care all that much, so I just nod my head because I don’t like getting stabbed with a fork.

Subversion

Bias alert.

Subversion is probably the source control system I’m most familiar with.

I’ve taught courses on how to use it in a purely graphical manner, I’ve written blog posts about branching and merging strategies using it, and I’ve managed SVN servers, repositories and source control strategies for pretty large development teams using the technology.

Does this mean I’m a huge fanboy and think everything else sucks?

No, not really.

As far as centralized source control systems go, I think Subversion is the best, but it definitely has its set of shortcomings.

Overall, though, it gets the job done and is fairly easy to use, so I like it.

Git

Git has basically become synonymous with source control.

Ask an under-25 developer today what source control is and he or she will most likely say, “What, do you mean Git?”

There is a good reason for this.

Git is… well… pretty awesome.

Really, it is.

As far as source control software goes, Git does pretty much everything you want.

It’s extremely powerful.

The basics are fairly simple.

And it's quick, efficient, and universal.

Git even has a pretty large company which supports open source and managed hosting for Git projects called GitHub.

Definitely worth checking out if you haven’t already.

Mercurial

Mercurial is kind of like Git’s evil twin brother.

Some people have said Git is like MacGyver, and Mercurial is like James Bond.

I’m not exactly sure what they are talking about—or what they are smoking—but I sort of get it.

Mercurial could be described as a little more elegant and polished than Git.

Same basic idea—they are both distributed source control.

Same basic functionality and features.

But, in my experience, Mercurial is just a little bit easier to use and figure out whereas Git is a little more arcane, but there are more ways to combine and hack things together.

So, essentially I’ve just described Mercurial by comparing it to Git.

Hmm, well that will have to do.

If you use both, you’ll see why.

It’s sort of like one of those pointless religious war type thingies.

Anything Else?

No, not really.

The main source control systems are pretty much these four with Git taking a huge—and I mean, HUGE—share of the market.

Yes, some people are off using other stuff and merrily humming along, but it’s much more rare.

So, there you go, now you have the basics of source control.

Remember to commit early and to commit often.

Oh, and please use meaningful commit messages.